Story vs. Narrative

It’s the way you tell it.

Narrative is the choice of which events to relate and in what order to relate them – so it is a representation or specific manifestation of the story, rather than the story itself. The easy way to remember the difference between story and narrative is to reshuffle the order of events. A new event order means you have a new narrative of the same story.

Narrative turns story into information, or better, into knowledge for the recipient (the audience or reader). Each story event is a unit of knowledge the audience requires.

A narrative is paradox, because it seeks to convey truth by hiding it. A storyteller arranges the items of knowledge in such a way that they are revealed gradually, which implies initially obscuring the truth behind what is told. Such deliberate authorial obfuscation creates a sense of mystery or tension, and creates a desire in the audience to find out what is happening in the story and why. In this sense, a narrative is effectively the opposite of an account or a report.

A report presents information in order to be understood by the audience immediately, as it is being related. A neutral, matter of fact presentation probably maintains a chronology of events. It explains a state of affairs blow by blow, and aims for maximum clarity at every stage. It seeks to convey truth by simply telling it. While the point of a narrative is also that the recipient perceives the truth of the story, in a narrative this truth is conveyed indirectly. Narrative is therefore responsible for how the recipient perceives the story.

In this article we’ll look at

- Story Basics

- The Components of Story

- Text Types That Describe A Story

- Author Choices: Genre and Point of View

- Causality in Narrative

Story Basics

First, let’s state some basics as we understand them here at Beemgee: a story consists of events that are related by a narrator; events consist of actions carried out by characters; characters are motivated, they have reasons for the things they do; there is conflict involved; one and the same story may be told in different ways, that is, have varying narratives.

Note that we are talking here about narrative in the dramaturgical sense – not in the social sense. Like the term “storytelling”, the word “narrative” has become a bit of a buzzword. We are not referring here to open “social narratives” such as “the American narrative”. For the definition and exploration of such collective narratives, see our article in The Bigger ‘Narratives’ of Society. Here, we are pinpointing the use of the term primarily for storytellers creating novels, films, plays, and the like. Such works tend in their archetypal form to be closed narratives with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

A narrative may present the events of the story in linear, that is to say chronological order or not. But the story remains the story – even if it is told backwards. And that’s the easy way to remember the difference between story and narrative: if you reshuffle the order of events, you are changing the narrative – the way you tell the story –, and perhaps its premise too, but you are not changing the story itself.

The Components of Story

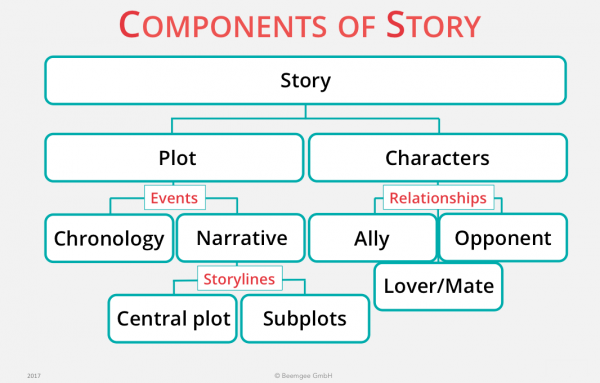

A story’s events may be arranged as chronology or narrative. That’s why there is a switch between the two in the Beemgee plot tool.

Let’s take “Story” as the hyper-ordinate term. Every story features characters that do something, and the total of these actions constitutes the plot. Plot consists of things that happen, i.e. events. These may be sorted into two different orders, the chronological sequence in time, and the order in which the author chooses to relate them, which is the narrative.

A story may furthermore consist of two or several plots or subplots – let’s call these storylines – which tend to meet and intertwine.

The events are what the characters do. They do these things because they are in interaction with each other. The interactions are linked to motivations. Essentially, the ensuing relationships can be boiled down to three different categories:

- the characters cooperate

- the characters are in conflict or oppose each other

- the characters get together, form a unity

Text Types That Describe A Story

One and the same story can be represented by different text types:

- Story

- Step Outline

- Treatment

- Synopsis

- Logline

All of these may be ascribed to the same work. They are different expressions of the same material.

The logline and the synopsis describe the story without telling it, in a sentence or a couple of paragraphs respectively. They are typically included in project proposals or exposés.

The treatment is a summary of the plot, including some of the most important events, but not all of them. Such a brief version of the story describes the same story as the full or finished version, but since this short version does not include the same (amount of) events, it is not the (same) narrative.

Both synopsis and treatment (and in extreme cases perhaps even the logline) may point out how the narrative works, especially if it is not chronological, but neither actually contains the narrative of the story because neither includes a description of each and every event.

The step outline describes all the events of the story in narrative order, as a sort of shortened meta-version of the story itself. While a logline, a synopsis, a treatment, a step outline, and the finished work may all refer to the same story, only the step outline and the finished work can express the same narrative of that story because they contain the same events without leaving any out. And as liars know, leaving out bits of information can change the narrative.

Author Choices: Genre and Point of View

An author has choices. Many, many choices. As we have seen above, an author has to decide on the narrative to be able to relate the story she has chosen to tell.

Furthermore, the choice of genre influences the reception of the narrative. The same events can be turned into, say, a comedy or a thriller. Here the execution, the manner in which the story is presented, determines how it is understood. Consider these examples: Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove and Sidney Lumet’s Fail-Safe use dissimilar narratives to tell similar stories that make comparable points about the threat of nuclear war and how it may come about. Or consider the novel Lolita – the story of the character Lolita would likely be salacious told by a lesser writer than Vladimir Nabokov.

Perhaps the greatest influence on the way a story is perceived by the audience or reader is the author’s choice of Point of View (PoV). Point of view describes from which character’s perspective the story is presented to the audience. Hardly any other author choice has as significant an effect on the narrative as point of view. Telling the same story from the various points of view of the participating characters creates differing narratives. This is the famous Rashomon effect, named after the 1950 film by Akira Kurosawa, which was based on a story by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa. Four times the same occurrence is shown, but as recounted by the four participants. The four narratives have very different effects on the audience’ understanding of the truth of what actually happened.

Such differences in understanding arise from the different motivations behind each character action, which we perceive differently due to the other point of view. Furthermore, one character may do something because she wants a particular result, but another character may ascribe completely different motivations to the same action, or observe different consequences to those actions. Even if the arrangement of the events is changed only very subtly, the chain of cause and effect is changed by the difference in point of view.

Causality in Narrative

A chronology is essentially a list of events. It implies temporality. Between each event you could insert the words “and then”. The aim of a chronology is to report what happened, so it is essentially neutral. But as humans, our minds will look for reasons why the events happened – the chronology might yield such interpretations or it might not. The juxtaposition of two scenes might seem to us to create meaning – when the audience experiences something and then the story cuts to another scene, the audience will be looking for the connection.

A narrative deliberately exploits the audience’ tendency to look for connections and figure out significance. Narrative implies causality. In a narrative you could insert between events the words “because of that …”. A narrative is an attempt at explanation by an author, as well as an act of interpretation by the audience. It carries meaning or a message (usually in form of a theme), which is brought home to the recipients or audience because they experience the narrative on an emotional level.

How and why things occurred, and how events relate to each other, is what our minds are unceasingly trying to figure out. We look for agency and causality. As such, narrative is not only the choice of an author, but is a technique our minds use in order to seek to understand our perceptions of a complex world – be it a story world or the real world. When we frame and shape our perceptions into a narrative, we reduce the feeling of living in a chaotic world and thereby have a greater feeling of control – because there is perceivable causality.

So could one argue that story is tantamount to truth in that it ultimately remains equivocal? Is story, like truth, an illusion created by narrative? We’ll leave you to ponder.

Related functions in the Beemgee story development tool:

Plot Outliner