A Character’s Plan or Perceived Needs

A character with a goal needs to do something in order to reach it.

The outward needs of a character – things she needs to acquire or achieve in order to reach the goal – divide the story journey into stages.

In storytelling, characters usually know they have a problem and there is usually something they want. They tend to set themselves a goal which they believe will solve their problem and get them what they want.

In order to get to the goal, the character will need something. Some examples: If the goal is a place, a means of transportation is necessary to get there. If we can’t rob the bank alone, we’ll have to persuade some allies to join our heist. If the goal is defeating a dragon, then some weapons would be helpful. If magic is needed, we’ll have to visit the magician to pick some up.

While the perceived need might be an object or a person, it usually requires an action. We’ll need a car, so do we buy one or steal one? We’ll need a sword, so do we pull one out of a stone or go to the blacksmith? If we need help, who do we ask and how do we talk them into joining us? We’ll need magic, but how do we find a magician? Ask an elf or go to the oracle for advice?

So, once the goal is set, a vision of the way to reach it opens up to the protagonist – and with that to the audience/reader. At the very least, the first step of the way presents itself. All this is what the character is conscious of.

In other words, the character forms a plan.

The plan is communicated more or less explicitly to the audience. The anticipation of how things will not go quite according to plan is part of the pleasure. There must always be surprises in store for the characters as well as for the audience.

Stages and Obstacles

The perceived needs are external insofar as they are plot requirements to solving the external problem. There are two things to note about all this. Firstly, the character is aware that she or he will first do this, may then do that and possibly the other after that. Secondly, we are setting up stages or legs of the story journey – for the character, for the audience/reader, and for the author to write.

The story therefore consists, on the surface at least, of the main character reaching the goal by going through several stages of a journey. The story journey is the way to the goal, which involves the character overcoming obstacles on the way. Each stage of the journey contains at least one obstacle. And typically, the obstacles get harder and harder to overcome as the journey goes on.

Quest and heist stories tend to announce many of the stages of such a story journey in advance, including the needs the characters perceive. Often this announcement of what is to come makes the story world feel more believable, because some of its components have been set up before they are actually reached. In The Lord Of The Rings, the journey the characters must set out on and some of the troubles they will encounter on the way are literally mapped out before they set off. In Ocean’s Eleven, the audience is presented the plan of how the robbery will be carried out, or at least part of it, before watching this set of actions being performed. The fun is seeing what goes wrong and not according to plan. In many other genres, the stages of the journey may not be announced in such a direct way, and may come as a surprise as much to the characters as to the audience. But there is always a succession of perceived needs.

Another example: Crime fiction and mysteries typically have an investigator finding out the truth behind the case. If it is a detective story, there will be many suspects to interview. Usually, after the mission is set it will be clear who at least the first person on the list to visit is. That’s the first perceived need.

Surface Structure

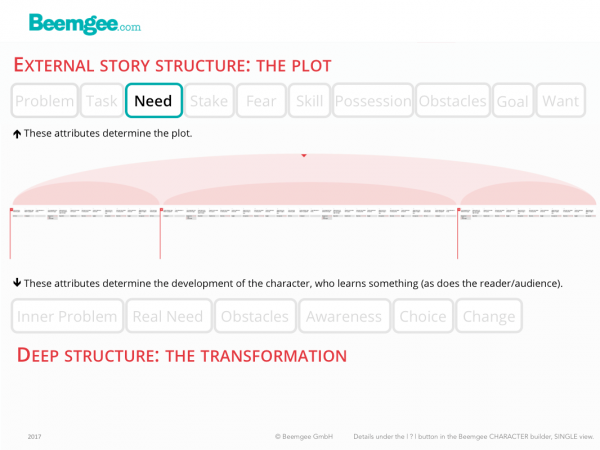

We have suggested that the story journey – the plan, the chain of perceived needs that is the way to the goal – is part of the surface structure of the story. Surface essentially means what the main character is conscious of. Beneath the surface, there may be a whole load of other things going on, starting with the internal problems of the characters. Of course, the author may be interested in exploring all sorts of other fields of meaning, using devices such as metaphor, allegory, symbolism, etc. In terms of dramaturgy, the surface structure amounts to plot and the deep structure to character development, i.e. what the character learns and how she changes because of this.

In other words, the surface structure is not necessarily what makes the story interesting. Nonetheless, every story needs such a surface structure. In order to make a story deep and meaningful, you must have the story. Once the author has that, she or he is able to imbue the plot and the actions of the characters with all sorts of depth and resonance. But without characters doing things, and through these actions forming a plot, the text will remain just that: a text. Such a text might be an intellectual masterpiece. But it won’t be an emotionally engaging story.

To add a deep structure to a story, it helps if the characters have emotional needs.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Already using the author tool? If not, try it here: