The difference between a character’s goal and what the character wants.

In a story, if the treasure is what the hero wants, then slaying the dragon is the goal.

The goal is what the character thinks will lead to the (satisfaction of the) want.

Since the treasure hoard has been there for ages, there must usually be some sort of trigger for the story to get started, i.e. for the character to want the hoard now, at the time the story begins. Often, an external problem creates such a trigger. It might supply a reason why the hero needs the hoard now, something more specific than just the general sense of wanting to be rich. Perhaps the hoard isn’t the reason at all. Perhaps there is a princess in distress, which certainly adds urgency to the matter. Either way, dealing with the dragon is the goal.

If somebody says the word “goal” to you, the image that springs to mind might have to do with the ends of a football pitch. The image is valid for our storytelling purposes, since the preposition associated with a goal is “through”. With the goal marking the end of the story journey, the character will get what he or she wants by passing through the goal to the happily ever after, i.e. the want, beyond.

At least, that’s what the character believes. See below.

It is helpful to distinguish between the goal and the want. Reaching the goal marks an important point in the story, often at the midpoint or concomitant with what is often referred to as the crisis. The want, on the other hand, is not a point but a state. As such, the want is somewhat more diffuse than the goal, and not really a part of the story journey, because if and when the character has what she or he wants, the story is over.

Two Techniques

One effective technique is the following: Set up the goal near the beginning of the story. Luke Skywalker sees Princess Leia’s message and sets out to help her. Humbert Humbert sees Lolita and sets out to win her. Then let the character achieve what she or he wants at the midpoint of the story. The second half of the story is then about the consequences of having achieved the goal.

Another technique is the “false goal”. Let the character believe that the goal is what is necessary in order to achieve what the character wants. The Prince hero who sets off to slay the dragon wants wealth, power and union with the Princess. But by the time this character reaches the goal, she or he has recognised her or his weakness, and she or he learns that the goal is not really what is needed at all. For instance, if the internal problem of the Prince is hard-heartedness, when he reaches the dragon he may have a revelation and decide not to slay the dragon, but tame it and take it home in order to guard the kingdom. His mercy will so impress the Princess that she will happily marry him.

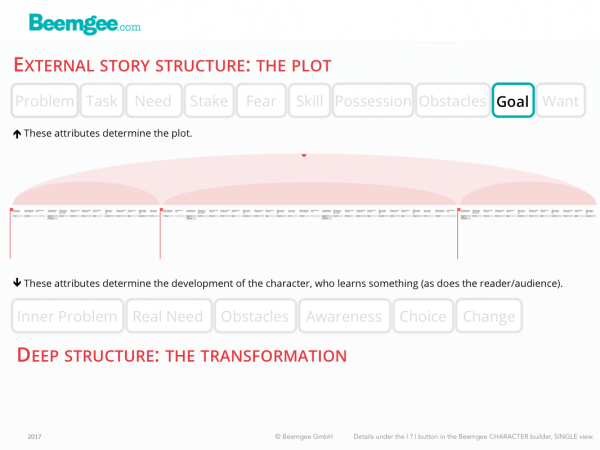

The Goal is Part of the Plot

In terms of the layers of the story, the goal is external, at the surface of the structure. It provides an explicit direction not only for the plot, but for everyone concerned: the audience or reader, the characters (especially the protagonist), the narrator, and the author. So we all know where the story is going, and the fun of it is journey. And let’s not forget that a story needs to be fun – remembering that what constitutes fun is relative to the ideal reader or viewer.

It is classic story structure to build a story by setting a goal for the character, having that character surmount obstacles on the way to the goal, and then manage to get through it (or not). The Odyssey works like this. Establishing a direction for the plot is in no way detrimental to achieving layers of meaning for the work.

A great way of creating more resonance and a deeper meaning is by showing an inner transformation in the character, beneath the surface structure of goal attainment. This may be achieved by creating an internal problem for the character, which results in the character really needing something other than the explicit goal.

If this is the case, then the character may realise upon reaching the goal that some sort of revelation, learning experience and emotional growth is required. All of that often entails that the goal loses its importance once the character has reached it.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer