Scene Type: Midpoint, the Pivotal Scene in Your Story

The midpoint is structurally the most significant point in a narrative.

Given that stories have a tendency to symmetry, the centre of a narrative should mark the zenith of the story arc, and with that, the pivotal point of the story.

So, to get to (mid)point: What happens in the middle of a story?

Here are some typical midpoint events:

- Something searched for is found (Star Wars IV, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lolita)

- A hidden truth is unveiled (to the audience, at least) – if not yet understood (Matrix, Pride and Prejudice, The Gruffalo)

- A dramatic event thwarts all plans made hitherto (James Cameron’s Titanic)

The centre of the narrative may be the discovery of something missing – in crime stories a vital piece of the puzzle may be revealed here (either to the audience or to the audience as well as the protagonist).

In any genre or dramatic category, the midpoint may be a moment of truth. This might be just a clue for the audience or perhaps an initial revelation of the true state of things.

If a character realises or finds out something that has so far been hidden, then this is the point at which the character begins to gain awareness. This counts in particular for the recognition of the character’s own internal problem. From here on the story might possibly lead up to a moment of choice at the crisis, when it becomes clear to the audience whether the character has learnt from this new awareness or not. In other words, the real need begins to overcome or supplant the character’s initial want due to what happens at the midpoint.

Some well-known examples of the midpoint

In the famous children’s book The Gruffalo, the mouse invents the creature of the title on the spur of the moment in order to scare off first a fox, then an owl, and finally a snake. In the middle of the story the mouse discovers that the Gruffalo does indeed exist. Thereupon the mouse meets (this time accompanied by the Gruffalo) the snake, the owl, and the fox – in reverse order! Perfect symmetry. The truth is revealed in the middle.

The midpoint is powerful and can swing the story into a new direction. Hamlet realises in the middle of the tragedy that Claudius did indeed murder his father. He takes action – and kills Polonius through a curtain.

The goal may be achieved at the midpoint. Indiana Jones finds the Lost Ark in the middle of the story; Humbert Humbert gets Lolita for himself when her mother dies in the middle of the story; Luke Skywalker rescues Princess Leia in the middle of the original Star Wars story. In these examples, the second half of the narrative deals with the consequences of the protagonist having attained the initial goal.

While a midpoint can be so subtle you might miss it (like Princess Leia saying to Luke Skywalker, “Aren’t you a little short for a Stormtrooper?”), in some cases the scene might be designed to be particularly memorable. The fully grown Alien in Alien doesn’t appear in all its horror until the middle of the movie. In The Godfather, it is Michael assassinating the competing mafia don along with the corrupt Police Chief. In The Godfather II, the midpoint is decidedly less spectacular but just as significant: Michael realises that his brother Fredo has betrayed the family. The consequence of this realisation only becomes apparent to the audience at the end.

The central fact of the story of the Titanic, the single most important action or event of this story, is that the ship hit an iceberg. When James Cameron made his film about the Titanic, he put the central event in the centre of the narrative.

So the midpoint marks the most significant point of change, a point of no return. After this, life cannot be the same for the protagonist, not until a new order is established at the end of the story.

After the midpoint, the forces of antagonism gather strength and close in.

The midpoint in theory

Given its striking significance, surprisingly little is made of the midpoint in narrative theory.

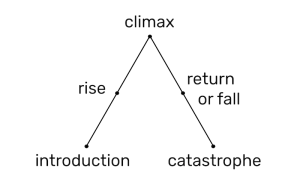

Gustav Freytag calls the midpoint the “climax”, but nowadays that term is generally used to refer to the final confrontation between protagonist and antagonism that typically occurs towards the end of the narrative. In Freytag’s terminology, the section of narrative after the “climax” is “falling action”, because he called everything that leads up to the midpoint “rising action”.

Gustav Freytag calls the midpoint the “climax”, but nowadays that term is generally used to refer to the final confrontation between protagonist and antagonism that typically occurs towards the end of the narrative. In Freytag’s terminology, the section of narrative after the “climax” is “falling action”, because he called everything that leads up to the midpoint “rising action”.

Freytag’s pyramid is more famous today than his novels, and to an extent it corresponds to the currently fashionable image of the “story arc”. An arc obviously heads downwards after its zenith, but Freytag calling it “falling action” seems counter-intuitive, since the build up to the final confrontation or dénouement feels much more like rising tension. After all, the midpoint escalates the action. Freytag’s unfortunate terminology may be one reason why he is now mostly relegated to academia.

How Checkov’s Gun relates to the midpoint

So, authors composing stories do well to consider which important scene or action is pivotal to the plot or provides the audience with a new understanding of the story. If you’re planning a plot, determine this one scene of greatest significance and place it as close to the exact middle of the narrative as you can.

Then consider all the scenes to the left and right of it, and see how they relate to each other. Arrange the scenes in such a manner that the scenes in the second half correspond to equivalent scenes in the first half. This achieves symmetry in the story.

The technique of foreshadowing or planting (also know as set-up and pay-off) is one of the most emotive of dramaturgical devices. Audiences react more strongly to dramatic events when they have been foreshadowed. And foreshadowing works particularly well when symmetry is taken into account.

So if you have 100 scenes, make sure scene 50 (or thereabouts) is highly significant. And if in scene 90 a gun is fired, see if you can plant that gun in scene 10.

Header photo by Ashish Rangwala from Pexels

Freytag’s pyramid by SinjoroFoster – Own work, CC0

Put the midpoint in the middle of your story: