Antagonistic Obstacles – Does Your Story Really Need Them?

When the bad guy makes the hero’s journey difficult.

Let’s say your hero or heroine is a falsely accused fugitive from the law. While on the run, every policeman or government agent is effectively an antagonistic obstacle. This is particularly the case if there is a specific character who represents the state and whose mission it is to catch the heroine. This detective or agent casts out the net to catch the fugitive, using all the instruments of the state at his or her disposal in order to actively thwart the heroine’s escape.

Or maybe your story is about a soldier behind enemy lines on a mission to find and destroy (or steal) the enemy’s new super weapon, or perhaps rescue an important person who has been captured. Any enemy soldiers the hero encounters are, of course, obstacles. One could say that they are external obstacles if they just happen to be there, like a patrol unit. But if there is on the enemy side a character who is aware of our hero’s approach and is actively seeking to stop him achieving his mission, then the soldiers and/or henchmen this character sends out to find the hero are not external obstacles but antagonistic obstacles.

As we have said before, this division into three classes of obstacles – internal, external, and antagonistic – is not cut and dried and need not be followed too strictly. But differentiating between the different kinds of obstacles a hero or heroine must face while designing and planning your story can lead to a more exciting plot, simply because you can disperse the obstacles systematically within the story journey and have all the different kinds of obstacle build up to a great crescendo at the climax.

Antagonism and Protagonism

The best antagonistic obstacles are visible and physical aspects of the main character’s dark shadow or polar opposite. The final great confrontation at the crisis towards the end of the story will likely feature a great final obstacle which may be antagonistic, and overcoming it will also mean overcoming the internal obstacle. So the antagonism is bound together with the protagonist’s inner problem.

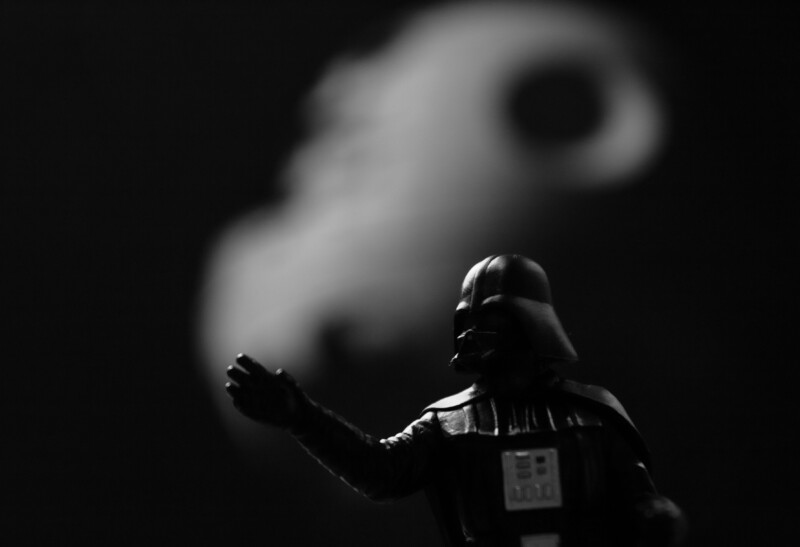

Protagonism represents a force or power in the construct of the story, usually in the form of one central character or hero – the protagonist. Protagonism has an equal and opposite force called antagonism. This power is often manifested in one main antagonistic character, who may have helpers or henchmen in the same way the protagonist has allies. So in Star Wars, Darth Vader is the antagonist, and the stormtroopers Luke Skywalker keeps bumping into are antagonistic obstacles. The greatest antagonistic obstacle is the Death Star. It is the sign of Darth’s concentrated power, is a physical manifestation of antagonism, and its destruction is the culmination of the quest. Once Luke has managed this feat, he has effectively come of age.

Telling It Differently

The common aspect of two opposing forces in conflict at the heart of so many stories of the western world often gives rise to the somewhat simplistic good guy versus bad guy story design. Contrary to popular belief, conflict between good versus evil is not archetypal storytelling and not a paradigm necessary to follow in order to create emotionally effective stories. As we’ve said elsewhere, if we didn’t have the concept of the Devil, we wouldn’t have Darth Vader. Good versus evil is as old as Christianity, but nowhere near as old as storytelling. If you look at stories from cultures with no contact to Christianity, you do not find the good versus evil paradigm.

Greek and Roman myths do not have good guys and bad guys. The Iliad describes neither the Greeks nor the Trojans as the goodies or the baddies. Achilles, Agamemnon, and Odysseus and Hector, Priam, Paris or Aeneas all have flaws, they make terrible mistakes, but unlike in so many war stories of the 20th or 21st centuries, it doesn’t occur to Homer to give one side the moral upper hand and make the other morally reprehensible. Neither the Greeks nor the Trojans are villains. The point of the story is not to root for the good guys and be cheered up when they win.

The pre-modern stories of China or Japan are full of conflict, but they don’t have overt good guys battling against evil bad guys. When you look at stories from the eastern world, only modern ones under the influence of Hollywood use the good vs bad paradigm. Watch the films of Studio Ghibli, such as My Neighbor Totoro, Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, or The Boy and the Heron, and see if you can find an antagonist. Is there some bad guy actively setting up obstacles for the hero? Not really.

Pixar learned from Ghibli. The success of Pixar Animation Studios quite probably has as much to do with their realisation that stories can work without antagonism and antagonistic obstacles as with their skill in digital animation. Who is the antagonist in Finding Nemo? We may not like the dentist or his daughter, but they are surely not arch villains. Toy Story, WALL-E, Cars and many more Pixar films manage to avoid baddies and the antagonistic obstacles they create.

Depending on the story, external and internal obstacles may be quite sufficient.

Image by Piotr Makowski on Unsplash

Click to develop a better story: