Why Is Crime Fiction So Popular?

Detectives and other investigators abound on our TV and cinema screens.

In the western world, crime fiction – mystery, thrillers, suspense, whodunnits, etc. – makes up somewhere between 25 and 40 percent of all fiction book sales. Why is the crime genre so popular?

Crime is fascinating, to be sure, because most of us don’t commit it. But the popularity of the genre has little to do with crime per se. It has far more to do with the very essence of how storytelling works.

In this article we will be looking at:

- Cause and Effect

- Agency

- The Whydunnit

- The Narrative Principle

- Why Some People Don’t Like Crime Stories

- The Search For Truth, or Gaining Awareness

- How Crime Is Like Comedy

Cause and Effect

Crime fiction exhibits most clearly one of the fundamental rules of storytelling: cause and effect. In crime fiction, you notice more than in other genres that every scene must be justified – each plot event must have a raison d’être within the story, because the reader or audience perceives every scene as the potential cause of an effect that comes later.

Even if a plot event turns out to be a red herring, then that herring is placed there for a purpose – i.e. of misleading the reader/viewer. And that is the point. Every scene has a recognizable purpose. In all fiction, scenes with no purpose might best be expunged. In crime fiction scenes with no purpose are least forgivable.

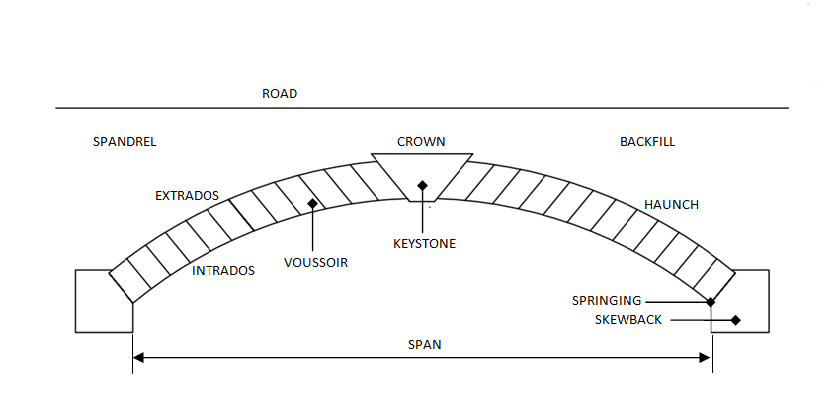

Picture an arched bridge. You know, the type the Romans built. Every stone is held in place by the other stones. Take away only one stone, and the whole structure falls to pieces.

Source: http://jaysromanhistory.com/romeweb/engineer/keyarch.gif

Source: http://jaysromanhistory.com/romeweb/engineer/keyarch.gif

Source: http://3.bp.blogspot.com/bridge.png

Fiction is a bit like that. Each scene supports the others, and an extra scene, a superfluous one, doesn’t have a place – or involves subtly changing all the others, just as you would have to adjust the shape of the other stones in the arch bridge if you were to add one more. Nowhere do you see this effect more clearly than in crime fiction. Crime fiction is cause and effect storytelling at its purest.

Agency

The universe has this law of cause and effect. But we as humans cannot really see it in action, because the universe is far too vast and complicated. We try to attribute causes to everything we experience, but mostly that is speculation. In other words, we seek agency – we look for the agent (the active or efficient cause, the person or thing responsible) of any actions we perceive. In real life, our judgments are often fallacious: we suspect far more specific agency than there actually is. The reason is a simple safety mechanism. It is safer to assume there is a specific threat (a sabre-tooth tiger behind the bush) than accept that the agent of a phenomenon might be so general as to be meaningless (the wind caused the rustle in the bush). Stories teach us to look for agency. In stories we are used to finding out who the agent of a phenomenon was – and nowhere more so than in a crime story. The whole story is built around discovering who committed the crime. So if stories exist in order to teach us something that will help us to survive – the evolutionary theory of why we humans love stories so much –, then crime stories do that with particular efficiency.

The Whydunnit

We don’t just look for meaning behind random phenomena by attributing agency. We look for meaning behind what people do. We think that what others do is motivated, that there are reasons behind their actions and possibly aims that might not be obvious. We are so attuned to living in social groups that trying to second guess why others in the group do what they do is something we do instinctively. We can’t help it.

Indeed, we tend to assume that people have motivations similar to our own. It is hard for us understand people who are, for example, less conscientious than ourselves – or more so. To understand the motives of the people around us is a very human need, we do it in order to be able to navigate our social environment. Crime fiction provides a sort of playing field to practice this skill. Because the interesting thing in a crime story is not really who did it, but why they did it. It’s rarely a whodunnit, more of a whytheydunnit. At the end of a crime story, the motive of the criminal must nearly always be revealed.

The Narrative Principle

Structurally, crime fiction is the purest genre. In classic crime fiction the narrative principle is particularly clear. The external problem as inciting incident is most obvious: the crime. The crime is external to the investigator’s life – until the investigator receives the call to investigate it. So the investigator is set a task, given a mission. The story sets up directly what the investigator wants: to resolve the crime. The investigator perceives the need to follow the first of the chain of clues that leads to solving the crime – that is the job, it’s what investigators do. The goal is to apprehend the criminal, that is the quest, achieving it will satisfy the want. An external problem, a call, a task, a want, an external need, a goal. All the elements of storytelling, all that the surface structure of any story exhibits – in crime fiction none of this is buried, it is not indirect, it’s not possible to overlook these elements, either as a reader or indeed as an author.

Why Some People Don’t Like Crime Stories

Probably the main reason some people don’t appreciate the crime genre is because it concentrates so expressly on the surface structure. What crime stories often don’t exhibit so meaningfully is the deep structure – not the internal problem and the real or emotional need of the main character, nor the change, the emotional development or growth of that character. In crime fiction, the resolution of the quest for the truth behind the mystery set up at the beginning of the story – the answer to the story question “whodunnit”, i.e. “who committed the crime?” – often takes the place of character development. For some people, that is not enough. That’s why crime fiction is often considered “lightweight” in comparison to more “literary” stories.

The Search for Truth in Stories

Consider this: All art, like all science and all religion, is in its very essence the search for truth. Truth about the human condition, what it is like to be living as a person in this world. In no genre is a search for truth more explicitly the subject matter. Who committed the crime? The whole story revolves explicitly about solving this problem, finding the truth of who or what is behind the mystery.

Because the whole point of any story – as with any art – is truth-seeking, when it is so direct as in crime fiction, the story is easier to consume, less demanding than stories that are not so obviously and directly about truth-seeking. That explains the apparent paradox of why reading about gruesome murders is somehow relaxing.

A search for truth culminates in a gaining of awareness. One of the secrets of how to compose great stories is conceiving the moment of revelation – the scene in which the penny drops for the audience –, and structuring the rest of the architecture of the story around that fundamental scene. The entire narrative is designed to lead stringently to the moment in which the audience is to have the aha-effect. This gasp, this “oh yes” in the audience, is achieved by various dramatic techniques, such as “planting” and “foreshadowing”. For the audience, it is one of the most satisfying moments of consuming a story. A novel, film, or tale around the campfire that does not have such a scene is less likely to be well-received. This general rule of thumb is true for stories ancient and modern, from any and all cultures, and irrespective of the medium in which they are told. And crime fiction follows this rule more distinctly than any other genre, because a crime story inevitably moves towards the scene in which the audience gains awareness of the truth behind the mystery. In the end, the audience must know whodunnit and why.

The interesting twist in crime fiction compared to other genres is that the protagonist of a crime story often does not exhibit change. In most stories, the main character learns something and grows emotionally – is a changed person at the end of the narrative. That cannot be said for most detectives in crime stories. This is due to a large extent to the pragmatic necessity of keeping the investigator as a consistent character for the next books in the series, the next episodes of the TV show. But it is also because the discovery of what was hidden, the revelation of truth, takes place in the audience notwithstanding. The effect necessary for the reader or viewer to feel that a story is satisfying, the effect of perceiving a change from the situation set up at the beginning to the situation at the end, happens with the “aha”-effect of finding out who the murderer is, rather than with seeing, aha, the character has grown.

How Crime Is Like Comedy

Comedy is an expression of the cyclical nature of life. Spring comes every year after winter. The sun rises after every night. This is one of the very deepest and most basic realities we are aware of as part of the human condition. This reality is structurally expressed in comedies – and in crime stories.

The other great fact of the human condition is death. Mortality is one of the deepest topoi of stories. Tragedy is the classical genre that deals with it most explicitly.

And of course crime fiction in its subject matter deals with death too. So crime fiction has deep similarities with two of the oldest and most classical styles of storytelling, comedy and tragedy. And therefore expresses almost everything there is to express through storytelling.

No wonder crime fiction is so popular.

Find out more about the Beemgee story development tool in this brief video: