Are the principles of storytelling really universal across cultures?

Take a look at your book shelf. Chances are there are European and North American authors there. Perhaps you have some Central or South American writers too. And maybe some Indian or Pakistani novels. And perhaps some Russians.

All of these authors wrote or write in the tradition of European storytelling, via colonial or cultural influence. Modern African authors writing novels, for example, have adopted this written prose text form although African storytelling traditions are primarily oral.

What most of us, at least in the western world, know about how to tell stories is influenced heavily by Aristotle’s Poetics. In this rather thin book, Aristotle describes some basic precepts of dramatic composition that continue to be circulated in creative writing classes and how-to books today.

Another strong influence on western storytelling is the protagonist/antagonist duality which arose along with Christianity. Would there be a Sauron without Satan? A Darth without the Devil? A Voldemort without Lucifer?

So what about stories that were created without any knowledge of Aristotle or Christianity? How are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different?

Let’s find out by asking …

How does classical Chinese literature differ from the western storytelling tradition?

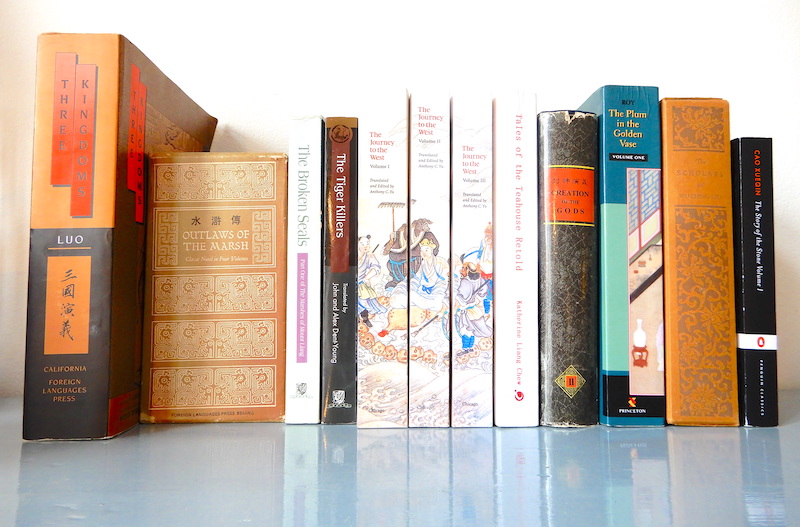

Considering the size of China and the country’s importance in world affairs, it seems quite astonishing how little-known the great works of Chinese literature are in the west – and how hard it is to actually find some of the books in our top 7 of Chinese literature.

Two reasons for this unfortunate phenomenon are:

- Chinese classical novels are almost all VERY long. Even the shortest on the list by far (The Scholars) weighs in at about 600 pages in English translation. For the others, somewhere between 1000 and 2000 pages is the norm.

- The dense network of references, allusions and intertextuality typical of the great Chinese novels is mostly lost on western readers, simply because one cannot recognise what one does not know.

That said, the various great works of Chinese literature consist of entertaining narratives with plenty of action and memorable characters. The style or storytelling is not inaccessible. The books in our list are not per se difficult to read.

China looks back on a rich tradition of storytelling, narratives, and literature. The short story form is ancient, with tales – especially of the supernatural – being collected and celebrated way before Beowulf was even born in Europe. Drama abounds, and poetry has a special significance as a way of expressing emotions. A number of substantial narrative histories written in prose were well-known to the intelligentsia of pre-modern Chinese. Furthermore, knowledge of particular texts on ethics and spirituality (for example the Confucian four books and five classics and the Daoist Tao Te Ching or Zhuangzi) was considered de rigueur for the official and upper classes.

The long-form novel came along quite suddenly just over 500 years ago. Generally recognised as the first great Chinese novel is The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which appeared around 1494 CE.

Journey to the East: 18 things to look out for when reading a classical Chinese novel.

1. Fictionality

The earlier of the books listed in our top 7 are based on existing material, in a similar way to how Shakespeare often adapted older stories and told them new. The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (14th century) is a novelisation of the Records of the Three Kingdoms and deliberately changes some details for dramatic effect. The Journey to the West (1592) is a fanciful retelling of the pilgrim’s own Records on the Western Regions, adding lots of fantastical and folkloristic elements. The exploits of the outlaws in Water Margin were based on a text history from the Song dynasty. Investiture of the Gods (1605) mixes up older elements of folklore, history, legends, and mythology.

The later Plum in the Golden Vase (1610) starts off by retelling an episode from Water Margin, which the contemporary reader was sure to recognise, but after a few chapters the storyline peels off into a new direction and the material becomes original. The Scholars (1750) tells of “types” of people (one feels not only real people but fictional characters too) but the plot lines are, while sometimes derivative, invented rather than culled from other stories. The Story of the Stone (1760) apparently has strong autobiographical elements, but the story is made up.

So we see a distinct progression towards fictionality.

2. Chapters and “Decades”

All the Chinese great classic novels are segmented into chapters. Within a novel, the chapters are generally of roughly equal length. Furthermore, they tend to show two major events each, which are referred to in the chapter title. For example:

Wang Yung Shrewdly Sets a Double Snare;

Dong Zhuo Starts a Brawl at Phoenix Pavillion

from Three Kingdoms, or

An evil demon at Black River captures the monk;

The Western Ocean’s dragon prince catches the iguana

from Journey to the West.

Not only are the chapters themselves organised according to a design principle. It is surely no coincidence that four of the seven novels in our list have exactly 100 chapters. Three Kingdoms has 120, as do the full versions of Water Margin and The Story of The Stone. The Scholars with its 55 chapters seems downright out of place by comparison.

A “major event” or narrative unit is called a mu. Two mu make up a hui, a double item chapter. Large books were printed in standard printing units called chuans – binding techniques couldn’t handle entire novels, and possibly longer stories appeared in serial form. Typically, such a bound book would contain five chuans, so an entire 100 chapter novel would mean 20 chuans, or volumes, on your shelf.

Furthermore, the internal dramaturgical logic of many of the Ming novels reveals a tendency to arrange plot arcs in such a way that they finish neatly within ten hui units. Thus it is possible to trace 10 “decades” in a hundred chapter novel, or 12 in Three Kingdoms or the 120 chapter version of Water Margin. So two chuans would often contain a more or less coherent and complete story unit, though this unit fits into the overall structure or narrative arc of the novel in its entirety too.

The discipline with which the authors maintain what are essentially structural conventions is truly remarkable, and establishes a mesmerisingly rhythmic reading experience. See 17 below.

3. Cliffhangers

Not only are the chapters rigorously organised, each one ends on an explicit cliffhanger:

Did Zhang Fei kill the Imperial Corps commander?

READ ON.

from Three Kingdoms, or

We do not know how the disciples manage to rescue the Tang Monk; let’s listen to the explanation in the next chapter.

from Journey to the West.

This design principle ensures that the novels maintain tension throughout their stupendous length.

4. Oral Storytelling Tradition

The novels arose at least in part out of an oral storytelling tradition. In China, storytellers – many itinerant – would set up at roadsides and hold sessions in which they would tell long tales. This was popular entertainment. One day’s session would end on a tense note to make sure people came back next day for the following session, which explains the strong cliffhangers and could account for the habit of making chapters of roughly equal length.

5. The Narrator

The influence of professional storytellers also goes some way towards explaining the dominant narrative tone in the classical Chinese novels, which is of an omniscient third person narrator who is discreet insofar as he or she does not take part in the action, nor is the situation of the telling of the story made explicit. There may be stock phrases akin to “gentle reader”, but on the whole, the narrator stands apart from the characters and does not draw attention to him or herself. For the reader of one of the classic Chinese novels, the experience is similar to listening to a roadside storyteller. And just as entertaining.

The great innovation came in 1760 with The Story of the Stone, the text of which is suddenly self-aware of itself as a story being told by a narrator who is not just unreliable but positively mystifying.

6. Poetry and Additional Texts

All of the novels in our Top 7 intersperse the prose narration with other text forms, especially poetry. These extra bits serve various functions, some of them quite significant. Think of the chorus in a Greek tragedy, only moreso. The inserted texts may be informative or a form of commentary. They add spice and flavour, and have rhythmic relevance. Translations that leave out these extra bits because they seem strange to western readers are missing important stuff!

Also, poetry is an important conduit for the expression of feeling. In many of the works listed above, characters at one point or another are so emotionally overcome that they write a poem. Sometimes this gets them into serious trouble later – in Investiture of the Gods a spur of the moment poem ultimately brings down an entire dynasty.

7. Transitions

Many of the works on our list, especially Water Margin and The Scholars, exhibit a bizarre and beguiling phenomenon. They concern the handover of the action from character to character, scene to scene. It seems Chinese narrative does not like cuts or breaks. Our skilled classical Chinese authors seem to have considered it naff or cheap to end a scene and have it be followed by a blank line and then have the next scene starting with different characters in a different location. Instead, they manoeuvre the characters and what they do in such a way that character X performs the action of a scene, then moves on and happens to bump into character Y (often at an inn), and then the narration follows character Y as he or she performs the action of the next scene, leaving X to go his way (though he may well turn up again later). The technique has been called “the ‘billiard ball’ shift in narrative focus, according to which we follow the course of one figure until he runs into another, whereupon the narrative then follows the new trajectory of the latter’s adventures, leaving the former in his tracks, perhaps to be reintroduced at a later juncture” (Andrew Plaks, The Four Masterworks of the Ming Novel).

The only work of western literature we can think of that follows this principle so stringently is JR by William Gaddis. But he didn’t use chapters.

8. Let there be Magic!

In the far east, the boundary between the earthly world and the other world is not as clear-cut as in the west. In stories, ghosts may appear, or protagonists might visit the underworld. There are “transcendants” with remarkable longevity as well as immortals, gods and goddesses, and heroes with special powers or weapons. All this may not seem fitting to “serious” literature for some western readers (too close to fantasy), but it happens to a greater or lesser degree in all the Chinese classics and really shouldn’t put you off reading them. Indeed, supernatural elements are integral and provide gateways to understanding profound truths about life – and death.

9. Officials and Scholars

The Chinese dynasties ruled an empire that varied in size and geographic extent over the centuries, but was always big. In order to control the empire, there was a complicated bureaucratic structure that was based on writing. Officials had to be able to read orders from the head of state, and had to write reports. Therefore literacy was a prime concern for this class in society, and for individuals a precondition for a lucrative and high-status career as an official.

In order to test literacy (through knowledge of classic Confucian texts) there was a complex examination system that endured for well over a thousand years until 1905, and which was tiered from local to regional to state exams. The significance of this system is perhaps exaggerated in literature because the people writing novels and books will probably have been part of it, in the sense that they are likely to have taken (and possibly failed and re-taken again and again) at least some of these exams. Furthermore, the audience for books – the literati – were pretty much by default also people for whom these exams were an important factor in life. Thus these exams feature somewhat more heavily in traditional Chinese stories than, say, farming.

The exams were open to males of any social class, but the privilege of a wealthy and educated family obviously made it easier to pass them. Officials are often known as scholars, and the novel The Scholars depicts this strata of society exhaustively.

10. Prevalent Themes

Two themes are found in all the great Chinese novels to a greater or lesser extent. They are:

- Loyalty and Filial Piety

- Religion and Syncretism

The relationship between the ruler and his (or in rare cases her) subjects is mirrored in the parent-child relationship as well as the host and guest relationship. The importance attached to these relationships takes some getting used to when reading the novels, for example when seating arrangements are meticulously described along with the courtesies exchanged between characters concerning where the host will sit and where the guest. Investiture of the Gods, for instance, revolves explicitly around an insoluble question of loyalty. A theme like this is, of course, not unique to Chinese literature. In Greek mythology, for example, one finds plenty of constellations of events that lead to similar moral quandaries revolving around such questions.

Classical China has three major religions that exist simultaneously and more or less harmoniously. This syncretism is very different from many other cultures, and that it is not such an easy matter is borne out by the fact that the relationship between the religions and how people deal with spirituality is a recurring theme in the Chinese novels. Journey to the West in particular deals with the co-existence of Daoism, Buddhism and Confucianism.

11. Numbers

Certain numbers seem to be hugely significant, because they recur again and again throughout all of the great Chinese novels. For example, look out for instances of 36 and multiples thereof. A few examples:

- There are 36 attacks on the Wu rebels in Investiture of the Gods.

- There are 72 sex scenes in Plum in the Golden Vase.

- There are 108 Outlaws of the Marsh.

- The Journey to the West is exactly 108,000 li (miles) long.

It is incredible how 36, 72, and 108 crops up again and again and again.

Actually, the basic number here is 9, which may be so resonant because very early Chinese settlements were organised into eight families living in a noughts and crosses style grid, the central field containing the well, dwellings, and other essentials for the community, and each of the surrounding eight fields would be cultivated by one family. Put four such niner-units together for a bigger village and you have the relationship of four to nine, 36 fields. But whether this is the origin of the prevalence of 36s is purely speculative.

The other great source of interest in regard to numbers is the vastly important I Ching, the Book of Changes, which explains the 64 hexagrams grouped into 32 pairs with 8 trigrams.

When you start looking out for any numbers mentioned in the texts (of characters, of incidents, of dumplings on a plate!), you soon come to believe that nothing that happens in these stories simply occurs because the author willed it so, but it all has some greater significance.

12. Allusions and Hidden Significances

A stairway is described as pointing to the East and a person arrives from the North. For a Chinese reader, this creates some sort of resonance in that it suggests death or a ghostly visitation. While such allusions and references are mostly lost on western readers, one nonetheless begins to feel the painstaking care with which these books are written and appreciate that nothing in them is left to chance. It all means something – which gives the books a sense of depth even when the meaning remains elusive.

Furthermore, among Chinese authors, referring to and quoting classical texts was considered erudite, to a degree that modern westerners might consider plagiaristic. The degree of intertextuality in the classical novels is higher than an average western reader could possibly hope to recognise.

Annotated translations may be preferable, if available.

13. Antagonism

In western stories over two thousand years old, be they Roman or Greek, you don’t really find goodies fighting out and out villains. Rather, characters make errors of judgement or stand for values that are in conflict with those of other characters. Ancient heroes make mistakes which may lead them to tragedy, or are simply not nice guys – Odysseus is morally dubious, Achilles is permanently in a huff. Even someone as otherwise positively connoted as Heracles murdered his wife and children. So in western storytelling, the “baddy” didn’t really get traction until Christianity spread. (For more on this, see antagonistic obstacles.)

Similarly, Chinese novels treat morality and ethical behaviour as strong and important themes, but usually without overt good versus evil in the story. Even the incredibly nasty baddy in Investiture of the Gods is no genuine villain.

14. Heroes

The term hero has somewhat different connotations in Chinese stories than to a western audience. It is used to refer to characters who choose to live a life less ordinary, but not necessarily to a protagonist of a particular story. Nor does the term perforce imply a morally superior stance. The 108 Outlaws of the Marsh are all heroes, though some of them are not particularly nice.

Perhaps, if there is less focus on an antagonist, there need also be less focus on a protagonist?

It could be said that in China the idea of striving is essentially futile, since the will of heaven has effectively preordained the success or failure of any venture. This rather weakens the point of individuals taking on great challenges or quests. Certainly classical Chinese fiction is less concerned with single heroes prevailing in the face of overwhelming odds than many western tales. In Chinese novels, heroes are rarely alone. They tend to find help in the form of a band or of allies.

Many heroes bide their time and act according to the situation, rather than pursuing a single-minded purpose. And most importantly, before taking a decision, a hero always seeks advice. Heroic is being able to tell good advice from bad and acting accordingly. In Three Kingdoms, no-one does anything without lengthy consultations beforehand. The only hero who spontaneously does as he sees fit is Sun Wukong, alias Monkey, from Journey to the West, and more often than not he gets into hot water because of it. Perhaps that is why he is such an outstanding and beloved character in Chinese literature.

Another aspect to bear in mind: Many of the great Chinese Ming era novels retell familiar stories with well-known characters. In particular Three Kingdoms and Outlaws of the Marsh feature heroes at least as well-known to the audience as Robin Hood and his merry men are in the UK and the western world. A central part of the genius of these novels is that the characters become far more complex and morally ambivalent than they had ever been in popular storytelling beforehand. Imagine Robin Hood not as a simple hero stealing from the rich and giving to the poor but with multiple dimensions and disturbing scenes of behaviour not in keeping with his persona.

The presentation of these complicated, deep, and often morally dubious heroes – their heroism deflated – is not quite like the psychological verisimilitude often sought in modern western novels, let’s say since Flaubert. Of the main characters in the novels, few (with the notable exception of Monkey) really transform or learn in the way that we recognise from modern western novels or movies, growing through revelations into more mature human beings. Nor do they stand for single emotions or behaviours in the way that, say, Achilles stands for anger in the Ilias. Instead, they display various emotional stances and sometimes it is hard to figure out their genuine motivations behind the pretences they hold up to other characters as well as to the audience. Who are these people really? How should we judge them? The interplay of the various characters in these vast novels points to the complexity of the human condition in general. The richly patterned tapestries woven in these novels reveal thought-provoking patterns of human concerns and mentalities.

Some of this artistry is perhaps due to the natural development of storytelling art. If we look at the history of cinema, the popular heroes of yore, Roy Rogers and all the rest of the “goodies”, gave way to more interesting popular heroes such as Indiana Jones, who had more quirks and flaws. In the twenty first century we have notably younger heroes and heroines, starting off with Harry Potter, and such stories make a great effort to show their heroes on the one hand as “everyman” (or woman) characters so that anyone in the audience can identify with them, and on the other as well-rounded, psychologically plausible, and interestingly flawed characters. So in a way we might assume that the heroes of Three Kingdoms and Outlaws of the Marsh have evolved into the fascinating characters they are in the novels through dozens and hundreds of retellings of the story material beforehand.

15. Cause and Effect

It has been suggested that in the far east the idea of cause and effect is not as prevalent or significant in storytelling because of the tradition of Yin and Yang and ideas of predestination. This may be something to look out for when reading.

For our part, we observe plenty of cause and effect in Chinese literature, because we clearly see consequences of character actions. With the stupendous length of the great Chinese novels, the consequences of characters’ actions may not become clear until many, many chapters later. These novels, then, are in this sense more like real life when cause and effect is not as obvious simply because of the passage of time and the many, many things that happen, which obfuscate the sense of causality modern audiences are used to in novels and films.

As in the west, a function of eastern storytelling seems to be to deal with the apparently random nature of human experience. The stories show potential causes for the things that happen to characters – whether these causes be of worldly human, spiritual, otherworldly or divine origin – and effects when they react to them.

16. Structure and the Seven Tenths Rule

Chinese novels are not averse to “long play-outs”. In typical western stories, the resolution quickly ties up all the storylines after the climax, so that the end section is usually as short as possible (with some notable exceptions such as The Lord of the Rings). This urge for a fast finish is not felt by Asian storytellers, it seems. In terms of act structure one might say that an eastern final act is typically longer than in the west.

Sometimes, instead of striving to wrap everything up in a hurry, the last act opens a whole new story arc (a phenomenon we first became aware of when we saw the classic Kung Fu movie The 36th Chamber of Shaolin). Nor is it essential that heroes survive until the end of the story – in Plum in the Golden Vase, the protagonist Ximen Qing dies in chapter 79 of 100, and none of the main characters of Three Kingdoms make it to the final chapter 120.

It may perhaps be more accurate to assume an underlying tendency to four acts in Asian stories rather than three. However, assuming that even in three act structure act 2 is divided by the midpoint into two sections, the structural difference is more one of degree than kind.

Symmetry is definitely as important a phenomenon to Chinese literature as any other stories. Again and again we see pivotal midpoints, a “watershed” in the centre of the narrative, and the mirroring in the second half of events or issues of the first half. The Three Kingdoms are established in the middle of the novel. Monkey goes back to heaven in Chapter 51 of the 100 chapter Journey to the West (humble this time, whereas in his initial visit he ruined the place). Ximen Qing acquires the aphrodisiac that will be the death of him “at exactly the midpoint of the novel [Plum in the Golden Vase], in chapters 49 and 50” (as translator David Tod Roy points out).

Furthermore, the “decades” we mentioned above, the ten chapter units of story, exhibit story arcs with midpoints too.

Very interesting, and connected with the idea of the long play-out or long final act, is the seven tenths rule. This phenomenon seems to be a Chinese special. Around seven tenths of the way through, something highly significant happens. In The Scholars, the high point of scholarly virtue is the building and consecration of the temple, which happens in chapters 36 (!) and 37 of the 55 chapters. Translator David Tod Roy points out that The Plum in the Golden Vase is divided into ten units of ten chapters each, with a twist or new development “usually in the seventh chapter, to culminate in a climax in the ninth chapter”. We see that the death of the protagonist in chapter 79 therefore adheres to the structural design.

17. Episodic or Repetitive

Chinese novels are sometimes criticised for being episodic, instead of having a clear plot throughline or story arc. Nonetheless, there is usually – as we have shown above – a design principle at work which, when you take a step back and review the overall story, demonstrates a high degree of structural organisation, foreshadowing, parallelism, and especially symmetry.

The ten chapter decades sometimes echo each other, with a later decade bearing a resemblance to a former one, but this time gaining in meaning or significance because of the existence of the former one. Furthermore, there are often recognisable “capsules” of plot, more or less self-contained stories spanning two, three, or four subsequent chapters. These “episodes” are distinct enough that they may be found as dramas or short stories in their own right (see 1, fictionality, above), much in the same way as Greek hero cycles such as the Iliad spawned plays built around specific events taken from the grander narrative. Next to the possible parallelism of decades, such capsules may be found to resemble each other and gain meaning with each new variation of a motif, theme, topos, or pattern of action. Recurrence is part of the design principle.

Episodes are therefore not just strung together haphazardly. There is nothing haphazard whatsoever about any of the great works of classical Chinese fiction. Consider an analogy from landscape painting: A single mountain may be brought into relief in the composition of a painting by placing another mountain behind it. The foreground gains clarity through the background. By retelling a similar story in another “capsule” with different protagonists, the novels take the time to represent another perspective, as if showing the background mountain in the foreground this time. Readers end up comparing – and understanding the nature of mountains much better than if they had seen only one.

18. Variations on a Theme: Cyclical Parallelism

One of the reasons for the criticism that Chinese stories are supposedly episodic is surely a failure or refusal to recognise the importance of cyclical narrative structure. For example, the story of one character may be very similar to the story of another character told in later chapters, capsules, or decades, but with subtle variations. Such recurrence of motif or action is not laziness on the part of Chinese authors, but is deliberate and conscious, and may serve various functions in terms of how the story is understood. The parallelism in terms of story content adds meaning, while in terms of structure (the chapters and decades) creates an astonishing rhythmic effect.

The idea that narratives are cyclical is nothing new to modern western writers and readers. For instance, the Hero’s Journey paradigm prescribes the “return” to the origin. The long Chinese novels add cycles within the greater cycle, which western audiences accustomed to “direct” and “straight-forward” narratives (directly back to the point of departure) may initially find dizzying.

However, this kind of structural device is found in some well-known western stories too. Stephen King does the same kind of thing in some of his longer novels, for example in It.

Consider an analogy from another art, music: In Chinese novels recurrence and cyclical structure is as par for the course as are variations on a theme in western symphonies by the likes of Bach or Beethoven. “Units” or “capsules” of plot are like movements in which themes can recur.

It seems that in Chinese fiction, a straightforward story arc is just too simplistic to cast valuable or meaningful light on the complexities of universal human existence.

Different, different, but same!

So are there differences between the western and eastern storytelling traditions? Certainly. But with the spectrum of fiction so huge, with so many stories of either tradition displaying such a wide variety of styles and topics, to concentrate on the supposed general differences would belittle the worth and value of the works of both Asian or European literatures.

Suffice it to say that looking to the east there is a world of literature as yet waiting to be discovered by most western readers. We can learn from the great eastern novels not only for the sake of the works themselves, nor even merely in the sense of what we may learn about the people of a continent which in the global geopolitical context today is simply important. We can also look at these great works of classical Chinese literature and see if there is anything we might learn about telling our own stories.

So which classical Chinese novels should you read? See our Top 7 here.

Test drive the Beemgee author tool now: