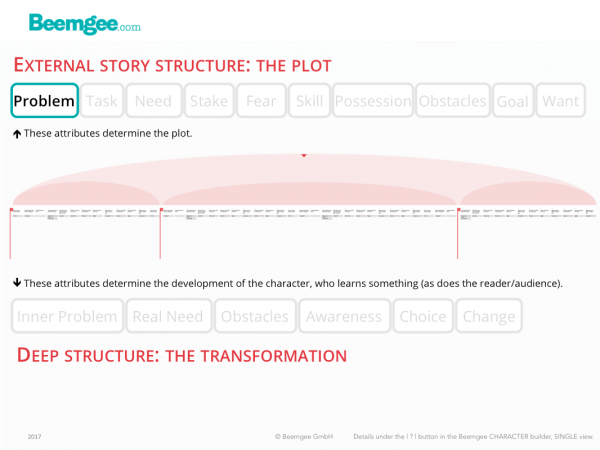

External Problem

In stories, characters solve problems. This is the basic principle of story.

Problems come in all shapes and sizes. What’s more, in storytelling they come from within and without. The problems that come from within are hidden, internal, and it is quite possible for a character not to be aware of them. They are typically character flaws or shortcomings.

But they are not usually what gets the story going. Most stories begin with the protagonist being confronted with an external problem.

The external problem of the main character triggers the plot. It is shown to the audience as the incident which eventually incites the protagonist to action.

In some genres this is easy to see. In crime or mystery fiction, the external problem is almost by definition the crime or mystery that the protagonist has to deal with. So at the beginning of the story there is a murder, the detective is called in to investigate and solve the crime. The case of the murder is the external problem – it has nothing to do with the protagonist until the call to investigate it. In adventure or quest stories the external problem is usually the task of attainment of a precious thing (the Lost Ark, the Maltese Falcon), or the destruction of a dangerous one (the dragon, the ring in Lord Of The Rings). So the external problem arises when the protagonist is assigned a mission to find, protect, accompany, destroy, etc. something or someone either valuable or dangerous.

By suggesting the story question, the external problem on the level of plot sets up what the story is about. Will Indiana Jones find the Lost Ark? Will Sam Spade retrieve the Maltese Falcon? Will Marty make it Back to the Future?

While in other genres the external problem may not be as sensational or spectacular, there is nonetheless likely to be one. Meeting a potential partner might be the external problem in a love story.

We are defining the external problem per character, so it is not completely synonymous with the term inciting incident, which is usually used to pinpoint one particular scene in the narrative. It is quite possible, even likely, that different events present the external problems of various characters. For example, in The Godfather, the external problem for the Godfather is conveyed in the scene of his meeting with Sallozzo. For Tom, the moment comes when he is kidnapped. For Sonny it is when he gets the phone call about the shooting. For Michael it is when Kay points out the headline in the newspaper to him.

Wanting the Solution

The external problem creates a desire in the character, i.e. to solve the problem. That’s why it is necessary as a component of story: to provide the reason for the story to begin now. The external problem acts as trigger, or starting gun, for each character. In many cases, the concept of external problem is directly related to the scene that is often called inciting incident. In this sense, the external problem is the prime mover of the plot of the story. It is the first domino that falls, the first cause of a string of events that affect the character.

That plots are built around the external problem is not new, by any means. It’s classical. Odysseus’ problem is that he is lost. Oedipus’ problem is the plague, which he learns was sent by the gods because of an unsolved murder.

The external problem causes the character’s motivation, i.e. to solve the problem. The protagonist wants a situation which is freed of the problem, which typically means reaching a goal. Attaining the goal will, in the character’s mind, solve the problem. In many stories, the goal is reached near the end of the story. What happens at the goal is the story’s climax.

But in some stories, the goal is reached much sooner, perhaps round about half way through. Then the story becomes about the consequences for the character of attaining the situation he or she wanted. This can mean that the external problem is replaced by another, often its opposite. Stories that work like this are said to have a midpoint or peripeteia. Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex works like this, so does Nabokov’s Lolita, or the oldest of the Star Wars movies.

However soon the protagonist’s problem is solved, each major character must have his or her own problem in order to create conflicting interests. In some cases, the problem and resulting want may be the same for several or all characters. Almost everyone in Raiders Of The Lost Ark wants the Ark, in the same way that the Maltese Falcon is the object of desire for each person in that book and film. Whether the characters have the same or different problems, the most important thing in the story is that the wants resulting from their respective problems result in conflicts of interest between the characters.

Why? Because conflict is a driving force of stories. Where does it come from? It boils down to the external problems the characters have. That’s why it is important for the author to be aware of each major character’s external problem at an early stage in the creative process of thinking up a story.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer