Guest post by Hayley Zelda.

Hayley Zelda is a writer and marketer at heart. She’s written on all the major writing platforms and worked with a number of self-published authors on marketing books to the YA audience. She loves working with teen writers and working with schools on literacy programs.

Writing is a craft that cannot be easily taught and from a young age, many students associate writing with homework and essays. By the time high school swings around, many teachers tell me they’ve given up on getting the majority of students excited about writing.

But I believe there is always a way to motivate and inspire young minds to get excited about writing. After all, storytelling has been in existence since the beginning of the human race. And who doesn’t love stories?

If it were a simple task, I probably wouldn’t be writing a blog post about it. Through trial and error, I’ve found a number of ways to help teens have fun while writing. This doesn’t mean that every teen will fall in love with writing forever, but at least some positive association can be built with the act of writing.

Here are some of my top tips on how to get young people excited about writing.

1. Use writing prompts relevant to what young people care about.

Writing prompts are a great way to get creative juices flowing. The more relevant you make the prompt, the stronger the response you’ll get from a student. (more…)

The TOUR guides you through the main features and functions. You can turn it on and off any time in your profile settings.

On-site help wherever you are in the tool under | ? |.

(more…)

How to set and assign recurring motifs to the plot events of your story.

(more…)

Highlight and Filter Your Scene Details.

(more…)

If you dont know what your story is really about, start finding out now (and don’t stop).

By Amos Ponger

Mankind’s Stories

The human ability of creating stories and the consumption and absorption of stories are very deeply connected to the core of our civilizations. Our efficiency as a species and cooperation in all scales of human endeavor rely on our ability to tell, decode, understand, and believe in stories.

Story has been so important for mankind’s cooperation, development and the way humans have understood themselves that all of our grand evolutions and revolutions – from the agricultural, religious, economic and cultural revolutions, the invention of money and law, the renaissance and humanism, the American, French and Russian revolutions, modernism, to socialism and capitalism – have actually happened through processes of rewriting collective Story. Revolutionaries and evolutionaries from Moses through Jesus, to Buddha, have actually risen upon a grand scale transformation of how humans understand themselves and cooperate with each other. And that has been done by story. Often the seeds of politics of whole centuries had actually been sown by poets, philosophers and prophets. STORYTELLERS.

Your Story

Now, even if you don’t plan on a revolution(more…)

The Writer’s Craft Super Stack.

Here is a resource that can help you hone your writing skills.

(more…)

Set the structure markers in the NARRATIVE order, see them in both sort orders.

(more…)

Stories tend to show characters getting together.

Stories don’t get going until there are at least two characters.

That’s because the characters in themselves are not really what interests the audience. What the audience likes to experience is relationships.

At a fundamental level, there are only these three ways that people – or characters within a story – can interact with each other:

- they can cooperate

- they might oppose each other

- or they may get together

It is the complexities of these types of relationship that authors present to their audiences.

At least two of the three types of relationships are likely to be depicted in any story, cooperation and conflict. To make the story feel complete, authors especially of popular stories such as Hollywood movies often include the third type in the form of a love interest. (more…)

Three sorts of opposition, and two things to remember.

Opposition causes conflict

For any character in a story, there may be opponents, not just for the protagonist. So while the protagonist-antagonism struggle may be at the forefront of the story, actually there is a whole system of opposing forces.

Let’s examine how characters in stories work against each other.

- Opposition can come from striving for the same or for opposite ends.

- Opponents can be antagonistic or incidental.

- There are two sorts of opponents, those from without, and those from within.

Same same or different?

An author might take each character at a time and arrange their opponents, which means characters who are either trying to get to the same thing first or whose success in attaining something else would thwart the character’s efforts.

In other words, the opposition (unless it arises by chance, see below) takes the form of either competition or threat. Competition for the same goal: Who will reach the South Pole first? Threat, because the goal of the opponent is opposed to the goal of the other figure: a nature reserve or a hotel complex. Imagine this for yourself using your own example: Your opponents strive for the same goal as you, and if your competitor wins, you get nothing. So your opponents are competing with you for the same goal, for example the same person. Or your opponent wants something completely different from you, and if he achieves that, it means you cannot get what you want. The success of the opponent is therefore a threat to your own well-being.

In either case, the opposition may be … (more…)

Want to see what a completed Beemgee project looks like?

Click one of the links below.

When the project opens, feel free to drag and drop or edit whatever you want – any changes you make will not be saved. It’s the perfect way to explore Beemgee functionality. Try the FILTER function, for instance, or the NARRATIVE-CHRONOLOGY switch. Go to the CHARACTER tool, mark your favourite character and hit DEVELOP in the tool bar. Or read the STEP OUTLINE.

If you don’t have an account yet, you’ll still see all the PREMIUM features, such as STORY QUESTIONS in the STEP OUTLINE section or the detail views of PLOT events or CHARACTER sheets.

THE GODFATHER

SEA BATTLES (Look closely, you might recognise this story!)

Have a look at a list of CLASSICAL CHINESE LITERATURE. Click the NARRATIVE-CHRONOLOGY switch to see the order of appearance and the order of when the stories are set.

Or disentangle the complex chronology of THE STAR WARS SAGA. Click the NARRATIVE-CHRONOLOGY switch to see the difference between the year of production and what happened when in the story.

Finally, read THE BEEMGEE STORY as a Beemgee project. Try opening the DESCRIPTIONs per event at the bottom of the sidebar, or read it as copy text in the STEP OUTLINE section.

(more…)

Why The Hero Is Never Alone.

Allies Embody the Principle of Cooperation

Despite their complexity and diversity, there are essentially only three different kinds of human relationships.

That’s right, if you take a step back and try to categorize human interactions, you’ll find three distinct types. Biologists know this, because the principle applies to any species that lives in groups. Within the group, three types of behavior may be observed:

- individuals cooperate with each other

- individuals compete with each other

- individuals mate

Evolutionary biologists describe a spectrum of individual to group selection. Some animals will typically try to maximize their individual gain, as exhibited in behaviors such as taking the biggest share of food or the best space for offspring, without regard for other animals in the group. On the other hand, some species have evolved social organizations in which individuals may act purely for the group’s benefit rather than individual gain. Think of ants, bees, or termites.

Interestingly, on this spectrum between profit maximization and altruism, homo sapiens sit pretty much exactly in the middle. Humans are genetically programmed to selfishness, to seek what is perceived as best for oneself and one’s immediate family, and at the same time have a strong and innate instinctive and natural urge towards cooperation and social behavior – which ultimately also increases our survival chances.

Cooperation, neighborliness, charitable behavior, acts of kindness – even if they costs us, they generally make us feel better and they make life in the tribe, clan, or community so much easier. Mind you, we do like to look after number one. We’re not going to simply give up our salaries, our homes, our lifestyles. Our own needs and those of our families come first. Who is not aware of this dichotomy?

The pull in opposite directions between egoism and altruism is perhaps one of the specifics of human beings as a species that has caused us to evolve abstract thought processes as well as complex societal and cultural forms. It also sheds light on basic principles of storytelling such as conflict. (more…)

Where a character comes from may determine their values.

It is not always necessary to explain where a character comes from. Knowing their origin may not help the audience to understand a character.

But for some stories, origins can be vital.

As an example, take a contrast story like In The Heat Of The Night. Police Chief Bill Gillespie lives in the USA’s deep south and is a racist bigot. Such are his values, and for the purpose of this story also his internal problem. That he is a racist does not surprise the audience at all. It is completely credible given his origins. He comes from an area where, at the time at least, such bigotry was rife, and when the African American detective Virgil Tibbs turns up, their conflict is utterly plausible.

What we’re getting at here is that the values of a character have to be made plausible to the audience, which may be achieved by making the origins of that character explicit. In many stories, where a character comes from has to be fitting to what that character is like. Their origin produces the character’s values.

Setting, Origin, and Story World

Are we talking about setting? Well, only to an extent. (more…)

By Lucia Tang.

Lucia is a writer with Reedsy, a marketplace that connects authors with editors, designers, and marketers. In Lucia’s spare time, she enjoys drinking coffee and planning her historical fantasy novel.

Whether we’re piecing together the timeline for a homicide or puzzling out the intricacies of Newtonian mechanics, cause and effect are crucial to how we make sense of, well, everything. Of course, I say “we” loosely. As writers, most of us won’t actually be catching killers or solving the coefficient of fiction. But still, stories are no exception to this rule: without cause and effect, they fall apart.

At the end of the day, writers should have as tight a grasp on causality as any detective or physicist. It doesn’t matter if you’re working on a doorstopper to rival War and Peace, or a breezy picture book for baby bookworms: you’ll need to craft a storyline that makes sense. This makes your readers want to spend time in the world you’ve created — and ensures they’ll leave it feeling enlightened and satisfied.

Of course, you can get there haphazardly, writing juicy scenes as they come to mind and attacking the chaos of your draft with a merciless red pen. But if you want to save time during the editing process, keep cause and effect in mind as you plot. (more…)

Six Suggestions to Beat the Block.

By Silvia Li Sam

By Silvia Li Sam

Silvia Li Sam is a storyteller, blogger, writer, and marketing expert. She has built communities of millions of people in education, tech, and non-profit. You can see some of her storytelling credentials on Medium at silvialisam.com, or connect with her on her LinkedIn.

What’s worse for an aspiring writer than to sit in front of their laptop with every intention of writing a great story, only to discover you can’t think of a single idea?

Don’t worry: we’ve all been there. All you need is a dash of inspiration, and you’ll be penning that story – or that novel! – in no time.

But how can you brainstorm great ideas? In this article, we’ll give you a few tips to battle writer’s block and never lose to it again!

1. Write down everything that comes to mind!

You might be asking yourself, “What am I supposed to write about? I don’t have any ideas!”

Don’t worry, the objective here isn’t writing anything exceptional, it’s just getting rid of the white page sitting in front of you. So type into your computer (or write down if you still use a pen and papers) anything you can think of. (more…)

It’s a bundle, and you’ll be laughing.

This is something we haven’t done before.

The Writer’s Craft Super Stack is a collection of digital tools, training, and resources that should help you improve your writing. In it you will find ecourses, ebooks, printable workbooks, access to 7 world-class pieces of software (yes, including Beemgee Premium), and lots more. (more…)

Beemgee helps authors develop their narrative material. The founder explains the benefits to authors and publishers.

By Tom Tivnan.

(more…)

(more…)

Why a Picture Book Manuscript Always Benefits From Systematic Planning

by Vincent Teetsov

Residing at the crossroads between songwriting, picture books, and non-fiction with a cultural focus, Vincent Teetsov is a communicator with the ambitious goal of inspiring the world to innovate and live meaningfully through multimedia creations. Since 2013, he has released several music albums and books, relating to topics of history, language, and the passage of creativity through time. This has been particularly impacted by his time living across the United States, Italy, and the UK. Since 2015, he has collaborated with illustrator Laani Heinar in creating the children’s stories, comics, and songs for Pumpkin and Stretch.

You can follow Vincent’s latest activity on Instagram here: www.instagram.com/pumpkinandstretch/ and here: www.instagram.com/vincentteetsov/.

Squeezing 90,000 Words Into 1,000

Admittedly, there is less text in a picture book than you will find in a novel. In a picture book, printing specifications typically dictate that there should be 32 pages. This even number allows for the story’s pages to be folded up neatly into a single stack, called the ‘signature’. After printing, the signature is then cut and bound together. Novels have less specific requirements.

With these differences in length, sometimes outsiders to the process of writing will assume that creating a picture book is easier. This is compounded by the fact that most picture books are written for children and use simpler language. Actually, it’s even harder to get this language right than when writing for adults. (more…)

What does meaning mean? When is a tale meaningful? A few perspectives on imbuing your plot and characters with a subtext.

It’s no mean feat to make your audience feel they have learned something through your story.

Meaning is that which is intended or understood. The audience draws significance, relevance or profundity out of a story when it understands the deeper implications, reasonings and causes behind it. The meaning of a story depends on the standpoint. An author may mean something different from what the audience understands.

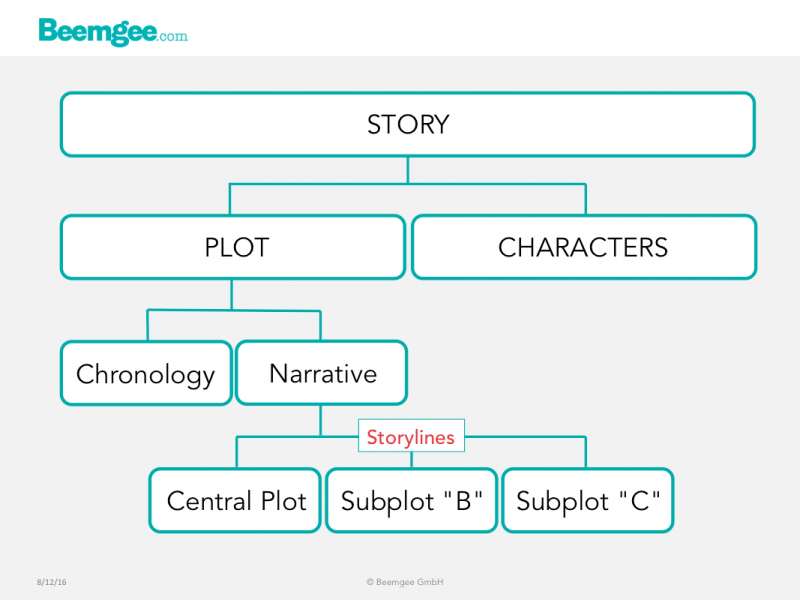

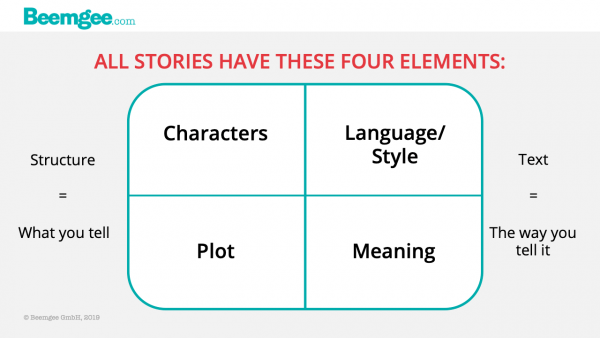

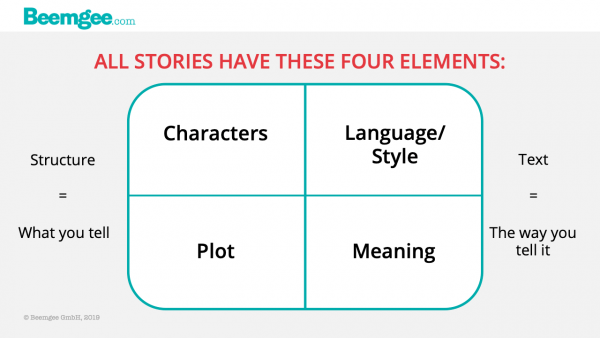

Let’s try to unravel this tricky but essential element of stories. We have noted that stories cannot help but exhibit four distinct elements:

- Characters

- Plot

- Style (aka language, or “voice”)

- Meaning

The interplay of characters and their actions form the plot, and all this is brought into a story structure, or narrative. Since there is always an author writing the novel or a team of people making the film, their stylistic choices determine the language of the work. In this post, we’ll skim the surface of the fourth element. Meaning is, of course, a broad term for something very hard to pinpoint.

We could add more story elements to the list. For instance, we have claimed that there is No Story Without Backstory. Furthermore, since the characters act within a time and place, there is always a story world. And in order to make the audience understand all this, there is always some measure of exposition. Then there is change or transformation, cause and effect, etc.

Let’s break down how we might look for the meaning of a story. (more…)

If a story is your original idea, then the copyright to it is by default yours.

However, copyright is a complex legal issue we cannot hope and don’t even want to explain properly here.

Each country has its own copyright laws. Also, copyright usually doesn’t apply until there is a pretty concrete manifestation of a “work”. It is easier to establish the copyright of the text of a novel than of the story the novel recounts. A story idea or even a fairly detailed outline may not qualify for legal copyright. But if you have a project in the form of a detailed outline which has a date to it, you have at least a way of asserting your moral rights to the intellectual property. (more…)

How does a publisher decide which manuscript to publish?

Nicole Boske heads the editorial team at Impress and Dark Diamonds, imprints of Carlsen Verlag.

Nicole Boske heads the editorial team at Impress and Dark Diamonds, imprints of Carlsen Verlag.

Even as a child I tried to discover the magic behind the printed word, and I knew my dream job before I started studying German. I always wanted only one thing: to help great novels find a home – in the hearts of their readers.

In the summer of 2014, my wish became reality. Under the shining grey sky of Hamburg I started as an editor for Impress and Dark Diamonds, both imprints of the famous publishers Carlsen Verlag [German publisher of the Harry Potter books]. As programme manager, a position I assumed in December 2018, my responsibilities also include planning and finalizing the programme and ultimately deciding which novels will be published. A pleasure as well as a challenge. We can’t publish all the manuscripts submitted to us, even if there’s an enormous amount of passion behind every single one of them.

But how exactly do we make a programme?

(more…)

Archetypal Antagonism in Documentary Film and Fiction

by Amos Ponger of Mrs Wulf Story Consulting

Stories are intricate mechanisms

Documentary film is a powerful genre that draws much of its energy from the material of real-life action. Consuming documentaries, we as spectators often ignore the fact that documentaries, like fiction, are a constructed clockwork of storytelling. Since the digital revolution, the amounts of raw material for documentary productions have probably grown tenfold, shifting much of the dramaturgical construction work to the editing room. Dealing with hundreds of hours of material you may say that 90 percent of the editing work in documentary film is “finding the story“, discovering what your story is about.

One issue editors often encounter while working on the narratives of documentary films is that many directors tend to neglect the importance of understanding and designing their antagonist or their antagonistic powers, the Antagonism.

Sure, you love your protagonists. You identify with their strivings and journeys, and you as a storyteller have probably given a lot of thought to making them appealing to your audience, giving the audience someone they can identify with. Your protagonists may be an inspiration to you, or you may yourself strongly identify with them, you may share or appreciate some of their characteristics and values.

At the same time you have probably not given your Antagonist/m the same attention. Have you? (more…)

In recent years, scientists have been writing books about the reasons why we tell each other stories.

Neurobiologists have discovered that when a person is immersed in a story, their brain patterns are similar to what they would be if that person were actually performing the actions they are reading about or watching. So if a recipient is emotionally engaged in a story, they are essentially “living” it – at least in terms of the brain patterns. The excitement is real, the fear, the empathy, the arousal. See Boyd, 2009, or Gottschall, 2012*.

Simulation

This has given rise to the analogy of the flight simulator.

Stories are everywhere. We create and consume them from an early age. Homo sapiens have done so for millennia – our modern media are a result of our ancient need for stories. We have been telling them to each other ever since we, as a species, have been human. It’s what homo sapiens do. It’s a defining characteristic. What evolutionary biologists call an “adaptation”.

That means there is a reason for us to tell stories: They help us survive. (more…)

What is the difference between commissioning editors, developmental editors, and line editors?

Photo by Patrick Tomasso on Unsplash

Let’s look at what each do to see the differences between the three different kinds of editors. And then find the other editorial task they all have in common.

The Commissioning Editor

An example (more…)

Virtual Reality technology (VR) has fascinating effects on storytelling.

Photo by NeONBRAND on Unsplash

The VR viewer wears special goggles and occupies a space within a virtual holodeck, which is created by two diagonally opposing little boxes shooting lasers out at right angles. The viewer can move within this virtual space, which might be the stage for a story. The goggles will show the viewer whatever program is loaded, Matrix-like. The 360° view is created quite conventionally, by filming a location in all directions, the camera at the centre, pointing outwards and panning all the way round.

So far, so good. It gets more interesting when such virtual locations are populated.

For VR, actors are filmed not with one or two cameras from a couple of angles, but with 40 or more cameras from all angles, the cameras all pointing inwards with the actor at the centre. The resulting 40 or more images are stitched together. The VR goggle wearer can therefore walk around the actors and see them from the front, from behind, from any angle. The actor was never at the location, but is superimposed into the virtual space (this already happens in conventional film with green screen technology).

What you get is the viewer as a ghost, moving about the story stage and around the characters at will. The effect is like intimate theatre. (more…)

by Amos Ponger

A pledge to transformational storytelling

Working for over 20 years as an award winning film editor and story consultant, Amos Ponger studied film science, cultural sciences, art history and multidisciplinary art sciences at The FU Berlin, Humboldt University Berlin and the Tel Aviv University. He has a Master’s degree from the Steve Tisch School of Film in the Tel Aviv University, worked as an editing teacher in two Israeli film academies, is senior advisor to our story development tool Beemgee.com, and recently co-founded the story consulting service Mrs Wulf. Book his services directly here.

The Transformational Process of Creating a Great Story

We all know that creating a great story is a process that can sometimes take many months and even years to fulfill.

If you talk to professional writers they will probably tell you that they have complex relationships with these processes of writing. Involving dilemmas, fear and joy, suffering and excitement. And that these self-reflexive processes are also processes of self-exploration.

Yet many writers, scriptwriters, filmmakers tend to put a lot of energy into their external journey towards completing their story, focusing on drama, act structure, “cliff hanging”, while neglecting minding their own internal processes on their journey.

What many film and story editors encounter while working with directors and writers is that authors and directors tend to have a very strong drive. They endure months in writing solitude, or filming in deserts, storms, war zones, perhaps even putting themselves in danger in order to realize their artistic vision. Yet at the same time very often they have a remarkable incapability of explaining WHY they HAVE to do it, and can only do so in very vague terms. (more…)

How narrative structure turns a story into an emotional experience.

Image: Comfreak, Pixabay

Storytelling is a bit of an overused buzzword. While we are all – by dint of being human – storytellers, how aware are you of the principles of dramaturgy? What exactly constitutes a story, in comparison to, say, a report or an anecdote?

And just to be clear, the following is not a story. It’s an how-to article.

Whatever the medium – film or text, online or offline –, storytelling has something to do with emotionally engaging an audience, that much seems clear. So is a picture of a cute puppy a story? Hardly.

Stories exist in order to create a difference in their audience. Stories always address problems and tend to convey the benefits of co-operative behaviour.

While there simply is no blueprint to how stories work, let’s examine the elements that recur in stories and try to find some patterns.

Who is the story about?

All stories are about someone. That someone does not have to be a person, it can be an animal (Bambi) or a robot (Wall-e). But a story needs a character. In fact, all stories have more than one character, with virtually no exceptions. This is because the interaction between several characters provides motivation, conflict and action.

Moreover, stories usually have a main character, the figure that the story seems to be principally about – the protagonist. It is not always obvious why one character is the protagonist rather than another. Is she simply the most heroic? Is she the one that develops most? Or does she just have the most scenes?(more…)

Antje Tresp-Welte is the winner of the Your Perfect Plot challenge set by BoD and Beemgee.

In her guest blog post, she gives frank insight into her writing process and her experiences with Beemgee.

Short stories were child’s play

Short stories were child’s play

When something intrigues me, I spin a story out of it. Until a few years ago I wrote mostly fairy tales, short stories for adults, poetry and stories for younger children, some of which were published in magazines. My story about a bad-tempered spectacled snake was published as a little book, “Charlotte and the Blue Lurker”. For all these stories I only sketched a few thoughts as planning and then wrote them down relatively quickly.

By now, book projects fascinate me too. Currently they are crime novels and fantasy for children from 8 or 10 years.

Long takes longer …

During a holiday at the North Sea I had the idea for my first crime novel. In it, the protagonist, an eleven-year-old very imaginative boy with a penchant for drawing, not only saves his grandma’s tea room from demolition, but is also involved in a mysterious story about a pirate who died long ago. I developed the original idea into a plot at a seminar for authors. I found the topic so great that I couldn’t wait to start writing it. Beforehand, I made notes on the individual characters and considered important cornerstones of the plot with the help of the hero’s journey. I started off with a great momentum and was soon able to read the first chapters to my son. Unfortunately his comment was, “Mama, that is much too long!”

… not to be longwinded

My two test readers came to a similar conclusion and I too had noticed that it somehow “grated”. I wasn’t really getting to the point. Was it due to my preliminary planning? Was it not detailed enough? I dived into the text, shortened passages, removed individual characters and worked out others more precisely. This changed entire storylines. At the same time my story gained more (narrative) speed and I found the tone for the language. (more…)

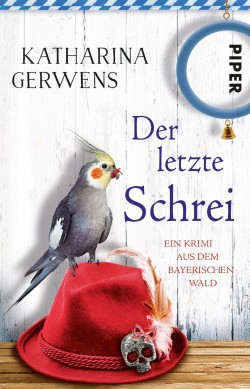

The first novel to state in black and white that the author worked with Beemgee.

This is certainly not the first book for which our author tool was used. But it is the first time that an author explicitly mentions Beemgee in her acknowledgements. Thank you, Katharina, we’re glad you use Beemgee during your story development!

All The Rage – Der letzte Schrei

All The Rage – Der letzte Schrei

published by the renowned Piper Verlag (Bonnier group)

Susanne Pfeiffer has recently joined the Beemgee team. She interviewed her friend Katharina Gerwens for us.

Beemgee: Congratulations, Katharina! It’s always great when you can hold your own book in your hands … How many novels have you published so far?

Katharina: This is my eleventh regional thriller published by Piper. Soon I’ll make it a dozen ….

Beemgee: I think ALL THE RAGE is a really good thriller title! You like double meanings. – But I want to get at something completely different: You know my foible to start every book by reading the acknowledgements – and here it says, last but not least, you worked on the plot with BEEMGEE! How so?

Katharina: Because for me any support I get is worth mentioning! I have asked so many people in my field about all sorts of things, and in these conversations new aspects have always emerged – the least I can so is say thank you! ALL THE RAGE is, by the way, the first book in which I worked with Beemgee – and it was a great help to me. (more…)

Reflections on dialectically guided writing, or: Can dialectics help us tell better stories?

Guest post by Richard Sorg.

Guest post by Richard Sorg.

Prof. Dr. phil. Richard Sorg, born in 1940, is an expert in dialectics. What is that, and what does it have to do with my novel? Well, “All great, moving and convincing stories are inconceivable without the central significance of the contradictions and conflicts that represent the driving energy of movement and development.” This puts us in the middle of dialectics. And of storytelling.

After studying theology, sociology, political science and philosophy in Tübingen, West Berlin, Zurich and Marburg, Richard Sorg taught sociology in Wiesbaden and Hamburg. His book “Dialectical Thinking” was recently published by PapyRossa Verlag. (Photo: Torsten Kollmer)

Ideas that contain a potential for conflict.

Sometimes there is a single but central chord at the beginning of a piece of music, even an entire opera, which is then gradually unfolded. Its inherent aspects, harmonies and dissonances emerge from the chosen, sometimes inconspicuous beginning, undergoing a dramatic, conflictual development, so that a whole, complex story emerges at the end of the path of this simple chord after its unfolding. This is the case, for example, with the so-called Tristan chord at the beginning of Richard Wagner’s opera “Tristan und Isolde”, a leitmotif chord that ends with an irritating dissonance.

The beginning of a story is sometimes an idea, an idea which you may not know how to develop. But some such ideas or beginnings carry a potential within them that is capable of unfolding and which holds unimagined development possibilities. ‘Candidates’ for viable beginnings – comparable to the dissonant Tristan chord mentioned above – are those that contain a potential for conflict or contradiction within. But it can also be a calm with which the matter is opened up, a calm that may then prove to be deceptive. We also find something similar in some dramas, for example with Bertolt Brecht.

And with that, we are already in the middle of dialectics. (more…)

See what’s new and track the continuous improvement of the Beemgee storytelling tool in these release notes.

2023

Podcast: The Beemgee Guide to How Stories Work

2022

Performance and security improvements

Payment update (now possible to pay in US Dollar or Euro)

2021

April: Updated system notifications | Improved logic in the global menu

2020

December: Cork board style view of plot event cards | Color picker for plot event cards | Choose to show or hide id and sort order numbers on plot event cards | Improvement of the PDF plot export | Categorisation of the plot attributes into scene info, structure, and process related attributes

June: Improvement ALL STORIES functionality | Layout optimisation of PDF exports | Premium PLOT attributes Dramaturgy, Hero’s Journey (new), Hero’s Journey (classic), Plot Beats, Story Anatomy, Audience’ Journey | Premium STEP OUTLINE attributes Author, Copyright holder | Premium PITCH attributes Genre, Audience, Similar to …, Period setting, Synopsis, Blurb in the STEP OUTLINE section

2019

November: Set Project Permissions (Premium) | Guest mode shows all features

May: Copy projects to create versions or drafts of stories (Premium) | Revised Tour

April: Export .rtf text documents (Premium) | Reorganisation of FREE feature set | Referral function

January: New servers (more…)

Stories are driven by yearning.

In order to get somewhere, there has to be a current position and a destination. Stories fundamentally describe a change of state – things are different at the end of the story than at the beginning. Hence a story has a starting point and a final end point, a resolution.

But that’s not enough. There has to be fuel, energy to power the motion between the one position and the other. In stories, this driving force is the motivation of the characters.

Motivation is so important to storytelling that we are going to look at several aspects of it. We’ll break it down into what we call the wish, the want, and the goal, all of which are interlinked but also distinct from each other. Here in this post, we’ll deal with the wish.

A wish is inherent in the character from the beginning. We might call it a character want, as distinct from a plot want (which we deal with elsewhere).

Some examples: (more…)

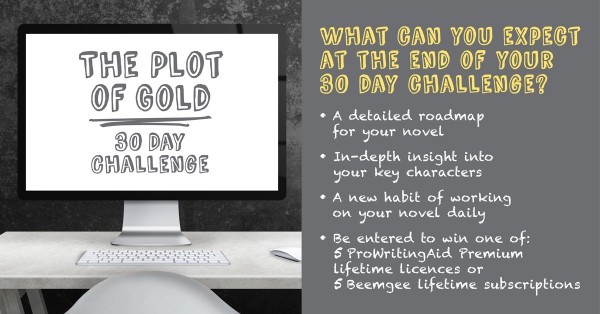

Beemgee and ProWritingAid are proud to announce the runners up and winners!

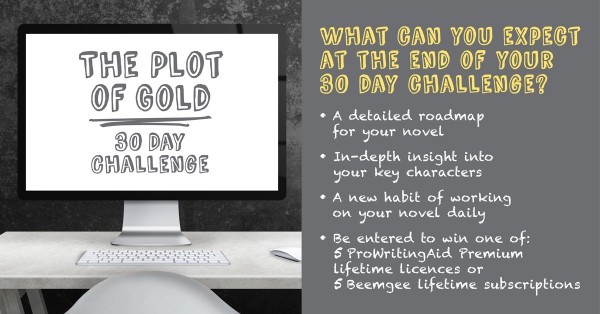

Every three days participants of The Plot of Gold Challenge received assignments per e-mail. Within thirty days, authors of fantasy, historical fiction, romance, and pretty much any other genre or style you can think of had complete outlines of their stories. Many submitted these to The Plot of Gold Competition.

Choosing the winners was much harder than the judges had imagined, since the standard of the entries was very high across the board. Thankfully, the PDF exports of the many Beemgee projects we received provided thorough insight into the nature of each story, including its strengths and weaknesses.

(more…)

“Where’s the story set?”

The answer provides many clues about the story in question. While we tend to ask “where”, the setting actually encompasses somewhat more than location.

In Film, the term location is generally used to refer to scenes that are shot outdoors rather than on a sound stage or in the studio. In the specific context of filmmaking, the word “setting” is often used in scripts is a hyper-ordinate term to refer to both types of shooting, indoors in a controlled environment and out “on location”.

But for stories in general, the concept of setting refers to rather more. Let’s find out how setting relates to

- time

- genre

- story world

- premise

Time

Each Star Wars story reminds us of the setting before it even starts: “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”. In being reminiscent of “once upon a time”, the famous opening establishes that the setting is essentially a fairy tale with spaceships.

“Middle-earth” is a valid answer to the question of setting for The Lord of the Rings. One might be tempted to explain that Middle-earth is a fictitious realm, maybe say something about how its quasi-medieval technology relates to the actual Earth’s history, or possibly mention the connection to the Midgard of Norse mythology.

So in addition to describing physical space, both these examples of setting contain hints and associations about the time when the events of the story take place. (more…)

Beemgee has come a long way. The features so far:

General

Free –

- FREE registration: Log into your account with your e-mail address and password.

- My Stories: Unlimited number of projects.

- Tour: Turn the guide to Beemgee’s basic functionality on or off at your leisure.

- Context-Sensitive background information on aspects of storytelling | ? |: On-site explanations and advice about each specific aspect of story development.

- “More About …” Buttons: Context-specific links to in-depth articles on each specific aspect of story development.

- Retractable Tool-Bar: Keep your workspace uncluttered by closing the tool-bar.

- Autosave: Project saves automatically after every change.

- Simple-Share: Share your story with your co-author, editor, producer, etc. (Attention: Working on one project simultaneously from several devices may lead to input loss – Beemgee always saves the newest version of the project).

- Work Offline: Continue working on your project even if you lose the internet connection (free features only) – the project will sync when you are back online.

- Language Switch: Use the tool in English or German.

Premium –

- Premium Registration: See and adjust your account and billing information.

- Copy stories to create versions (drafts).

- Permissions: Set a project to private, view-only, or can edit.

- Detail Views: See detail views of character sheets, pot events, and your step outline.

- Export PDFs: Character Sheets, Plot, Step Outline, Project – with selections for narrative/chronology, all attributes or input only, etc.

- Export RTF text files to re-import in writing software for treatments or as manuscript document.

CHARACTER

(more…)

(more…)

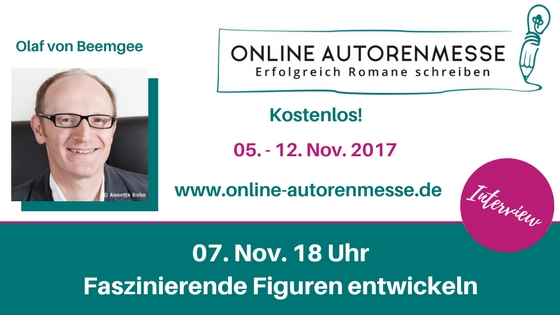

If you speak German, this online congress could be for you!

From the 5th through to the 12th of November, bestselling authors and experts from all fields of storytelling and (self-)publishing are giving advice, knowledge and tips on everything to do with writing and selling novels and stories.

It’s all free on www.online-autorenmesse.de.

Beemgee is taking part too. Hear what we have to say about how to create compelling characters on the 7th of November at 6 p.m. CET. Click the banner to register for free to the online author fair:

ProWritingAid teams up with Beemgee to run the 30 Day Plot of Gold Challenge

To enter, click here: Plot of Gold.

What do we mean when we talk about story structure?

A story is a complex entity comprising many interrelating parts. The author imposes some sort of organising principle onto the material, turning the story into a narrative. The result of this forming or shaping of the material is the story structure.

Certain structural markers are so explicit that the audience is aware of them, such as chapters in novels. Elizabethan plays are typically divided into five acts. A film script is broken down into acts, sequences, and scenes.

The beat is the smallest unit of story, below the scene in the structural hierarchy. It is the space between an action and the reaction it causes within a scene.

- Beat

- Scene

- Sequence

- Act

- Story

A plot event is not part of this traditional hierarchy, being more of a meta-unit somewhere between beat and scene.

Scenes and acts are defined in screenplays, like chapters in novels. But stories have structures that are not usually made obvious or explicit.

Beats

There are two different understandings of the term beat.

A scene may be broken down into beats – marked only by the moments when the mood or relationship the scene describes changes. Two characters are having a conversation, character A says something which makes character B react in a different way from what A expected – that’s a beat.

The term beat is also sometimes used when marking such changes on a bigger scale, across an entire narrative. Some screenwriters work with so-called beat sheets; in the Beemgee outlining tool, the plot event cards are perfect for creating beat sheets, since each card is designed to stand for one plot event. In a beat sheet, a beat is one unit of plot. If you think of narrative as a chain of events, then each beat is a single link. In one school of thought, a Hollywood movie is ideally constructed of exactly 40 such beats. (more…)

BoD and Beemgee are looking for heroes!

Click here to take part in the competition!

Archetypal Storytelling – Triggering Emotions

Free talk on how stories are structured to make us feel a certain sequence of emotions.

DATE AND TIME

LOCATION

UPDATE: The winner is … Call for story outlines by Beemgee, Ink-it and CONTEC México 2017.

This is Yolanda Prieto Pardo, whose story outline LOS ALTOS VUELOS DE JOSEFINA was chosen in the Fiction without Friction contest we ran with Contec México and Ink it. She has won a lifetime subscription to Beemgee Premium. Furthermore, our friends at Ink it will publish the novel online all over the world in 85 countries.

Congratulations Yolanda!

The CONTEC/Beemgee “Fiction without Friction” call for stories

Many innovations relevant to authors of stories and “content” apply to publication and distribution. However, digital aids can also help creators right from the moment they have their first ideas.

With Beemgee.com, fiction authors have a tool that helps them organize their plots and develop their characters. When it comes to pitching the work to a publisher, a Beemgee project provides a powerful supplement to the traditional exposé.

For publishers and other content disseminating organizations, Beemgee is a new tool that increases productivity during the evaluation process and considerably improves the workflow between author and editor/producer/publisher.

To showcase this new approach, CONTEC and Beemgee are running a call for stories, which the ebook platform ink-it is supporting.

Turn your story into a book for sale in over 40 online stores! (more…)

Author and creative writing teacher Jesse Falzoi was born in Hamburg and raised in Lübeck, Germany. Back in the nineties, after stays in the USA and France, she moved to Berlin, where she still lives with her three children.

She has translated Donald Barthelme stories into German. Her own stories have appeared in American, Russian, Indian, German, Swiss, Irish, British and Canadian magazines and anthologies. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Sierra Nevada College.

Her new book on Creative Writing is released end of May 2017.

At the age of twenty-one I quit university and bought a one-way ticket to San Francisco, USA. I wanted to get far away from my first attempts to grow up. I wanted to get away from a frustrating relationship and boring courses and everything that was pushing me to take life more seriously. I didn’t have any plans what I would be doing in San Francisco but I had the address of an acquaintance I had made a year before. I went on a journey that was physical in the beginning and became more and more spiritual during the process. I bought a return ticket in the end and went back to my hometown just to pack my suitcases for good; I’d be staying in Germany, but I wouldn’t be staying home.

(more…)

The process of writing is unique to each author.

There is no right or wrong way to write a work of fiction. Perhaps the main thing is to just sit down and get on with it.

Many authors start by writing the beginning of the story and working their way through to the end. This seems intuitive, as it mirrors the way narratives are normally received – from opening to resolution. Furthermore, it allows a development of the material that feels natural, beginning probably with a setting and a character or two and growing in complexity as the story progresses.

But this isn’t the only way to get a story written. The author is not the recipient, after all. The author is the creator.

Creative habits seem to differ according to medium. Most screenwriters spend a lot of time working out the intricacies of plot and complexities of character before beginning to actually write the screenplay. Some novelists, on the other hand, seem to require the writing process in order to get to grips with the material. For such authors, the act of working on text is so intimately intertwined with the craft of dramaturgy that the shaping of the story has to be performed simultaneously with the writing of it.

Flow

In some cases, a writer might have a fairly clear idea in mind where the story is headed, or already be aware of certain key scenes that ought to be included. In others, the author may not know how the story ends(more…)

From the point of view of one of the founders.

Hello there,

I’m Olaf. Despite my name, I’m British, but I moved to Berlin in the 90s. Until a couple of years ago I worked for big German publishers. Like (I suspect) many people in publishing, I harbored the secret desire to be an author. Such was my ordinary world.

One day I met my friend Amos for coffee. He is a filmmaker, and we spoke about a movie he was working on as well as the novel I wanted write. We discovered that we knew of no online tools conceived to help authors structure and outline their plots. This was the inciting incident for my own story.

After I had spent a few days ruminating, I noticed that I had a clear idea of what I expected of an outlining tool. So I started researching what was on the market. And I found … nothing. At least nothing that came close to what I saw in my mind’s eye.

So I went to Robert, whom I knew professionally and respected for his integrity and acumen. I told him I was thinking of a web-based software for authors, but that I would only conceive it if he would be my partner.

To my delight, he needed merely a few days to agree. Our journey had begun. (more…)

The logline is probably the hardest sentence to write.

The logline sums up a story in one sentence. This sentence should be memorable and clear, which means it is unlikely to be much longer than thirty words or to have complex syntax.

Once your reader has read your logline – or your listener heard it –, they will ideally know the following about your story:

- who it is about

- what the central conflict or main problem is

- what the most important characters do in the story

- why they do it, i.e. what their motivations are

- how they do it

- where all this happens, i.e. what the setting is

- when it happens, i.e. what the period is

The first of these points even counts double – since usually the logline should convey not only who the main protagonist is, but also what antagonism she faces.

What’s the logline for?

The purpose of the logline is to pitch your story.(more…)

Conflict is the Lifeblood of Story.

In real life, conflict is something we generally want to avoid. Stories, on the other hand, require conflict. This discrepancy is an indicator of the underlying purpose of stories as a kind of training ground, a place where we learn to deal with conflict without having to suffer real-life consequences.

In this post we will look at:

- An Analogy

- Archetypal conflict in stories

- Conflict between characters

- Conflict within a character

- The central conflict

Along with language (in some form or other, be it as text or as the language of a medium, such as film) and meaning (intended by the author or understood by the recipient), characters and plot form the constituent parts of story. It is impossible to create a story that does not include these four components – even if the characters are one-dimensional and the plot has no structure. However, it is formally possible to compose a story with no conflict.

It just won’t be very interesting.

In terms of narrative, conflict is presented as a series of confrontations of increasing intensity. If there are no confrontations – no battles of wits or fists, no crossing of swords or sparring with words – there is little to hold the audience’ attention. To create confrontations, there must be at least a of conflict of interest between the characters.

Conflict does not occur at particular points in a story. It permeates the whole of it. It expresses the values transported by the story’s theme. It creates at least two options of choice, both of which must appear to some extent reasonable and justifiable to the protagonist, particularly at the moment of crisis.

(more…)

Beemgee is holding free coaching sessions for authors at the Leipzig Book Fair 2017.

Submit your story outline by the 18th of March 2017. All you have to do is send us your Beemgee project. You stand a good chance of winning one of our 8 coaching slots of 40 minutes each!

We’ll give you free advice, tips and tricks about your story structure that will help you make your plot more dramatic and your characters more engaging – in person, live at the fair. Our help will focus on how you want to develop the material, whatever the genre or format.

What you have to do to win this prize:

Outline your story as a Beemgee project. It doesn’t matter whether you do this with a FREE project (TRY FOR FREE on www.beemgee.com) or with a PREMIUM account. Your content may be in English or in German. Your outline must have:

Send us an e-mail including the link to your project and your name to: story@beemgee.com. Alternatively, send the e-mail directly out of the web-app using the share function. (more…)

Blogposts and articles by Beemgee

Right here is where we list articles we publish on platforms and websites other than our own.

Writers Write | The Pros (& Cons) of Outlining

CONTEC México | “Fiction without Friction” Call for Story Outlines

Alliance of Independent Authors advice center | How to create better plots by concentrating on the characters

Alliance of Independent Authors advice center | How to structure archetypal stories: Putting your readers’ emotions first (more…)

The step outline is the scene by scene (step by step) account of what happens in the story.

Like a textual storyboard, the step outline presents the narrative in its entirety – without actually being the narrative. It is a complete report of the story – in the present tense! – that describes every plot event.

Cause and Effect

The step outline therefore makes one of the most important principles of storytelling very clear, cause and effect.

Apart from the kick-off event and the closing event, every plot event fulfils two functions, at least to an extent:

- It is a precondition of events that follow it in the narrative

- It is an inevitable consequence of events that have preceded it in the narrative

The step outline should make it easier to understand how the individual events relate to each other in this chain of cause and effect. The step outline may thus be read as the author’s construction plan of the narrative.(more…)

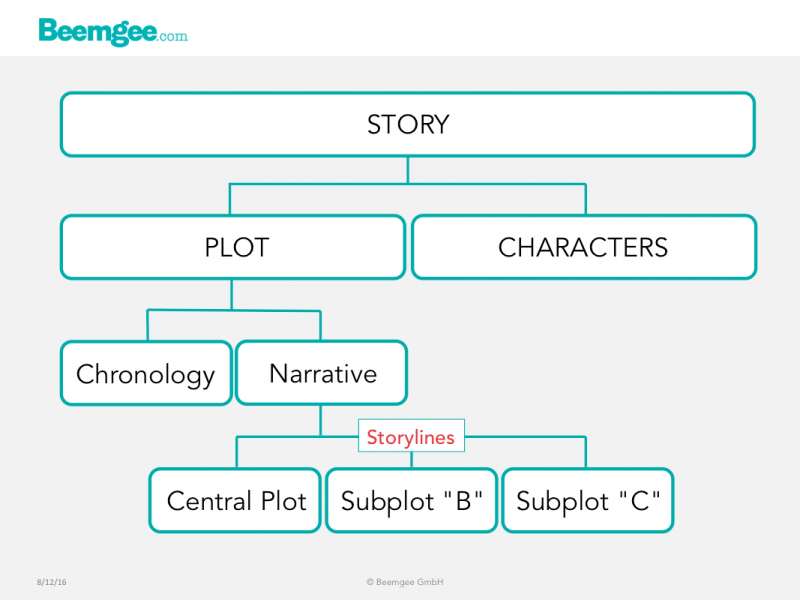

A plot arises out of the actions and interactions of the characters.

On the whole, you need at least two characters to create a plot. Add even more characters to the mix, and you’ll have possibilities for more than one plot.

Most stories consist of more than one plot. Each such plot is a self-contained storyline.

The Central Plot

Often there is a central plot and at least one subplot. The central plot is usually the one that arcs across the entire narrative, from the onset of the external problem (the “inciting incident” for one character) to its resolution. This is the plot that is at the(more…)

The term motif refers to any recurring element – in storytelling as in music or other arts.

Examples of elements that turn up repeatedly within a whole are an image on a tapestry or a particular sequence of notes in a symphony. The dispersal of these elements creates a pattern. It is therefore part of the artist’s craft to have some sort of design principle determine this pattern.

What motifs do

Motifs do not make a plot. But since they make patterns they are part of the structure of a story. And they help add a layer of meaning.

In other words, if a motif is present excessively in the first half of a story, and hardly at all in the second, then the author had better be aware of a reason for this uneven distribution. The distribution – the pattern – carries meaning to the audience. Remember, the audience yearns for meaning, is always striving to understand what the story is trying to convey at any given point. This demand for some sort of raison d’être for each element of a story, or for a sense of order within the whole, may well be unconscious to the audience much of the time, but ultimately the experience of the story is more satisfying when the audience can work out reasons and meaning.

In stories, motifs can be almost anything. Objects, actions, metaphors, symbols, colours, or images can be motifs. What defines an element as a motif is the systematic deployment within the story rather than the thing itself.

How motifs work

Motifs work best when(more…)

By Silvia Li Sam

By Silvia Li Sam

Nicole Boske heads the editorial team at

Nicole Boske heads the editorial team at

Guest post by Richard Sorg.

Guest post by Richard Sorg.