Frankfurt Book Fair 2016

One of the world’s largest events in publishing.

From the 19th till the 21st of October 2016, Beemgee will be quite active at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Come see us! (more…)

From the 19th till the 21st of October 2016, Beemgee will be quite active at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Come see us! (more…)

This blog is about storytelling and story development. We examine how fiction works and what stories really consist of, concentrating especially on plot and character development. Many of the posts are inspired by functions and features of our outlining software. It’s all about the craft of creating stories. (more…)

However, this way of categorising types of opposition is not equivalent to internal, external and antagonistic obstacles. Any of the three kinds of opposition listed above may be internal, external, or antagonistic. It depends on the story structure.

External opposition

In any story, the cast of characters will likely be diverse in such a way as to highlight the differences and conflicts of interests between the individuals. In some cases, certain roles may be expected or necessary parts of the surroundings, i.e. of the story world. In the story of a prisoner, it is implicit that there will be jailors or wardens, whose interest it will be to keep the prisoner in prison, which is in opposition or conflict with the prisoner’s desire for freedom.(more…)

In the western world, crime fiction – mystery, thrillers, suspense, whodunnits, etc. – makes up somewhere between 25 and 40 percent of all fiction book sales. Why is the crime genre so popular?

Crime is fascinating, to be sure, because most of us don’t commit it. But the popularity of the genre has little to do with crime per se. It has far more to do with the very essence of how storytelling works.

In this article we will be looking at:

Crime fiction exhibits most clearly one of the fundamental rules of storytelling: cause and effect. In crime fiction,(more…)

Photo by Jack Moreh on Freerange

But “hero” is a word with adventurous connotations, so we’ll stick to the term protagonist to signify the main character around whom the story is built. Sometimes it is not so easy to know which is your main character.

Generally speaking, the protagonist is the character whom the reader or audience accompanies for the greater part of the narrative. So usually this character is the one with most screen or page time. Often the protagonist is the character who exhibits the most profound change or transformation by the end of the story.

Furthermore, the protagonist – and in particular what the protagonist learns – embodies the story’s theme.

For simplicity’s sake, let us say for the moment that in ensemble pieces with several main characters, each of them is the protagonist of his or her own story, or rather storyline. Since the protagonist is on the whole a pretty important figure in a story, there is a fair bit to say about this archetype, so this post is going to be quite long.

In it we’ll answer some questions:

Some say the protagonist should be the most interesting character in the story, and the one whose fate you care about most.

But while that is often the case, it does not necessarily have to be true.

These do not have to be spectacular action events – they can be internal psychological events if your story is about a man who does not leave his room, or spiritual events if you are recounting the story of Buddha sitting beneath the tree. But events there must be if there is to be a story.

In this post we’ll discuss –

Events in a story are effectively bits of knowledge the author wants to impart – in a particular order, the narrative – to the recipient, i.e. the reader or audience. The story is told when all the pertinent knowledge has been presented, when all the bits of information necessary for the story to feel like a coherent unity are conveyed. An author(more…)

We have discussed time a great deal in this blog. Of course, the spatial dimension may be just as relevant.

We may distinguish between the overall story world location and specific locations. By story world we refer to the overall setting and logical framework of the story. This is always unique to the story, although that becomes most obvious in stories set either in a fantasy world (like The Lord Of The Rings) or in stories that have a setting tightly bound to a geographical feature, such as Heart of Darkness, Apocalypse Now, or Deliverance. In each of these latter examples, a river – and the journey up or down it – provides the story world. Yet story world is more than just physical location. It describes an entire environment, including the ethical dimensions. Consider Wall Street or The Big Short, stories that describe a “world” where making money comes first.

The setting is usually established in the first part of the story, and the rest of the story should be true to what has been set up at the beginning.

Within the entirety of the “world” come the specific locations(more…)

This may seem like a silly question. How long is a piece of string, right? And the simple answer is:

There are norms that have developed over time, and which are more or less inculcated into us due to our exposure to stories in their typical media. Back in the 1970s or 80s a music album contained a total of about 40 minutes of sound, because that is as much as would fit on a long-playing vinyl 33 rpm record, approximately 20 minutes on either side. With the advent of the CD, suddenly musicians felt the artistic need to create albums that were twice as long.

You’d think that stories wouldn’t be subject to such constraints because the carrier media for stories are more flexible. However, when it comes to moving pictures at least, what is typically considered a fair attention span to expect the audience to tolerate does seem prone to popular beliefs by industry players in the respective markets. For example, a typical feature length film is roughly two hours long. This is practical because cinemas can comfortably manage two screenings an evening. If the film is good enough, it could of course easily be longer, but at some point viewers become restless and need an intermission.

A typical two hour-ish movie has between forty and sixty scenes. Formatted according to industry standards, a screenplay has approximately as many pages as the finished movie would have minutes. In terms of plot events, some people in Hollywood believe that a commercial movie should have exactly forty (which in Beemgee’s plot outlining tool would mean exactly 40 event cards).

Content and form may be mutually determined, to some degree at least. A short story is usually considered such if it has less than 10.000 words. By dint of its length, a short story probably concentrates on one character’s dealing with one specific issue or occurrence, and is unlikely to have subplots or multiplots (that is, be about more than one protagonist).

Short stories are great practice for writers cutting their teeth. Our friends at the self-publishingschool have gathered 11 Easy Steps for Satisfying Stories.

A piece of written prose fiction between 10.000 and 50.000 words is often considered a ‘novella’. This is a sort of hybrid between the short story and the novel. The narrative of a novella is likely to cover more ground – that is, relate a longer and more complex set of events – than a short story simply because it is longer than a short story. But to state that a novella perforce has more depth or more action than a short story would be a meaningless generalization. What is likely is that the focus in a longer narrative such as a novella is on a string of occurrences (or chain of events, i.e. causally linked events) rather than the story revolving around the meaning and effects of a single occurrence. (more…)

These obstacles come in various forms and degrees of magnitude. And they may have different dimensions: they may be internal, external, or antagonistic.

Often the obstacles that resound most with a significant proportion of the audience are the ones that force the main characters to face and deal with problems within themselves, in their nature. In other words, with their internal problem.

Internal obstacles are the symptoms of the characters’ flaws or shortcomings, i.e. of the internal problem. The audience perceives them in scenes in which the character’s flaw prevents her progress.

Not every story features characters with internal problems. An internal problem is not strictly speaking necessary in order to create an exciting story.

But it helps.

The Emotional Truth

An internal problem makes the character appear fallible – and thus more credible, more human, more like us. Internal problems are invariably emotional and private. They express(more…)

Dialog enlivens stories. But dialog in stories is very different from real spoken language. It conveys information that the audience needs to know in order to understand the story as well as the characters – the one speaking the lines as well as the one reacting to them.

There is the rule of thumb that it’s better for the author to use action to explain things or move the plot forward than dialog, at least in film. Certainly, when the author makes characters say things solely to convey some bit of knowledge to the audience or reader, the lines tend to feel false. That’s a form of exposition, explanatory stuffing. If in doubt, leave it out. You’ll be surprised how much the audience understands even without explanations.

On the other hand, Elmore Leonard noted how readers don’t usually skip dialog. People like dialog. Dialog can be exciting. Dialog can be action. So authors had better know how to write it.

Here are seven things you ought to consider about every single line of dialog you put into your characters’ mouths. We’ve created this free table to help you. Feel free to download, use and share it.

1

If you’re writing(more…)

Determining the emotional core of a character in a story may lead to a clearer understanding of that character’s behaviour, i.e. their actions.

What we’re getting at here is essentially a premise for creating a story. We have noted that if you plonk a group of contrasting characters in a room – or story-world –, then a plot can emerge out of the arising conflicts of interest. If you’re designing a story, one approach is to create the contrasts between the characters (their essential differences of character) by giving each character a core trait or emotion. One character may be frivolous, another penny-pinching. One may be fearful, another cheeky.

You might object: Isn’t that a bit one-dimensional? Aren’t characters with just one core emotion flat?

Not necessarily. Focusing on one core emotion is not a cheap trick. It is as old as storytelling.

Ancient(more…)

Guest Post by Connor Rickett, 05/06/2015

Connor Rickett is a former professional scientist, current professional blogger and writer, travel enthusiast, lover of learning, and reluctant participant in social media. He is currently in the early stages of fortune and fame: debt and infamy.

Check out Cities of the Mind, his site for writers and freelancers looking to get better at what they do!

The Problem

All too often, the working writer finishes a draft of a story or book, only to find big stretches falling flat. There’s just something missing. It happens to published authors, too; I think of it as the “Second Book Curse”. This is where the writer has built a character, and things just work out a little too well for them. Sure, they’re challenged, put in mortal danger, thrashed a little bit, but, somehow, the tension from the first novel is gone. Most good writers seem to figure this out, and coming roaring back in the third book. Or maybe you just never read the ones who don’t.

But why does this happen? And, more importantly, how can you avoid it? (more…)

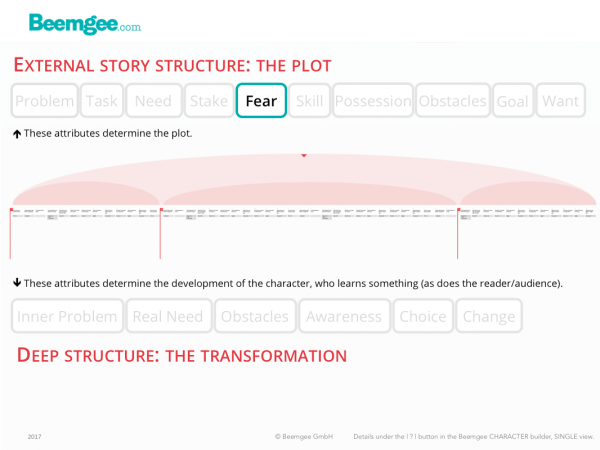

If a character in a story has loved ones, losing them is an even stronger fear.

A story engages the audience or readers more strongly when there is something valuable at stake for the character, such as his or her own life or that of a loved one. So giving a character a universal fear is usually a good place to start.

Giving a character a specific fear to overcome requires this information to be placed early in the narrative. The fear is then faced at a crisis point in the story, usually the midpoint or the climax.

Characters can have specific fears. A fear which is specific to one character must be set(more…)

Presumably your emotional reaction would be stronger if the child fell off the boat. Because you know that the child’s life is at stake. The first situation is not life-threatening, the only thing at stake is the dryness of the man’s clothes and his self-esteem.

The degree you care about events that happen to people, and to yourself, is directly related to what’s at stake. This applies as much to fictional characters as in the real world.

Hence it is immensely important for storytellers to(more…)

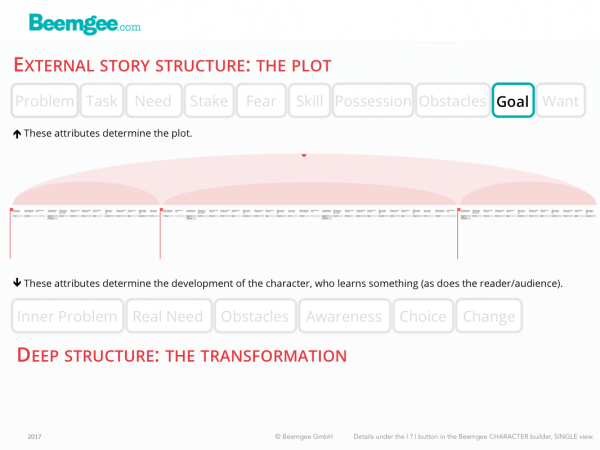

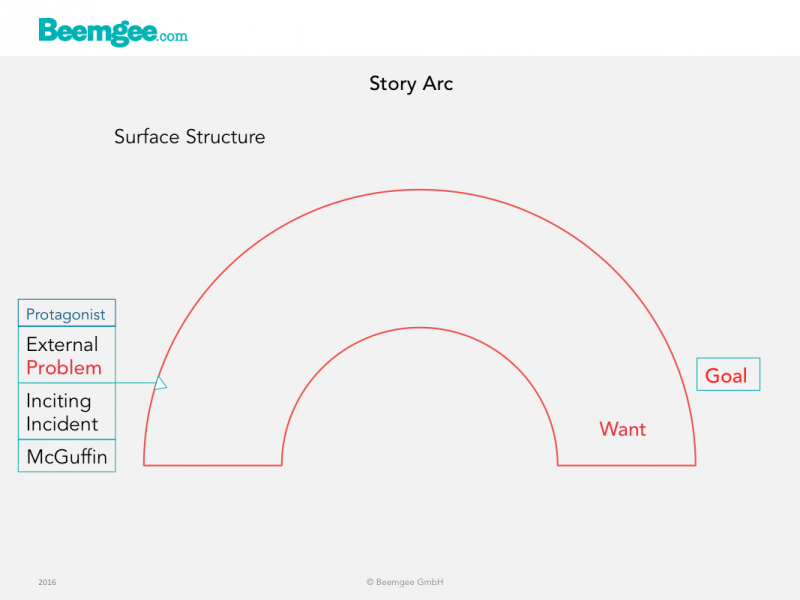

The goal is what the character thinks will lead to the (satisfaction of the) want.

Since the treasure hoard has been there for ages, there must usually be some sort of trigger for the story to get started, i.e. for the character to want the hoard now, at the time the story begins. Often, an external problem creates such a trigger. It might supply a reason why the hero needs the hoard now, something more specific than just the general sense of wanting to be rich. Perhaps the hoard isn’t the reason at all. Perhaps there is a princess in distress, which certainly adds urgency to the matter. Either way, dealing with the dragon is the goal.

If somebody says the word “goal” to you, the image that springs to mind might have to do with the ends of a football pitch. The(more…)

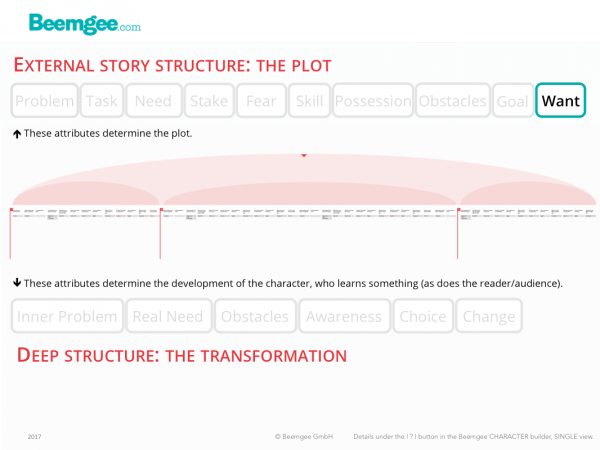

We can distinguish between two different types of want:

Marty McFly wishes to be a musician (character want). He also wants to get Back to the Future (plot want).

The wish or character want is a device which adds cohesion to the story, usually in the form of the set-up/pay-off. Marty is seen at the beginning of the film practicing the guitar; at the end of the film he plays at a concert. A character-inherent wish is a useful technique to make the character clearer to the audience, but it is not essential to composing a story.

Indispensable is what we have called the plot want. As a result of the external problem – the trigger event that sparks the chain of cause and effect which the bulk of the plot consists of –, the character feels an urge, which provides the motivation for the character’s actions in the story.

The want is the state for which the character strives, and is distinct from the goal.

In this post we’ll be talking about active vs. passive characters, motivation, the difference between a want and a goal, a couple of writer traps to avoid, and contradictory wants.

Characters have to be actively acting of their own volition. The want has to be urgent and strong enough for them to do things. If the want is missing or too weak, the character will lack motivation and appear passive. A passive character is usually not interesting enough to hold the audience’ or readers’ attention.

Why is this so?

Evolutionary explanations of stories attempt to shed light on the phenomenon. When characters react to events rather than cause them, they appear weak, as victims in a chaotic, uncontrolled world. Which means that there is not much we can learn from them. Humans try to see cause and effect in everything, not just in stories. And humans experience stories physically and emotionally (our hearts beat faster, our palms sweat), so there is really not much difference between how we experience a story and real life. Since we learn from experience, we instinctively prefer stories which provide us with experiences that benefit us in some way. In stories we vicariously experience or practice primarily social problem-solving, without suffering real-life consequences. We tend to learn more when we experience stories of self-motivated problem-solving.

There is a good reason for that cliché about actors always asking about their motivation. It is motivation that prompts the characters in a story to do the things they do. Stories seem to work best not only when characters are active rather than passive, but often when they have comprehensible reasons for their activity.

The reason for what a character wants is usually comprehensible for the audience or reader because of the external problem. In simple terms, the character wants to solve the problem. Take the Cinderella story as an example. Her problem is that she is bound to the stepmother and her two nasty daughters.

In other words, the want is a vision the character has of his or her situation without the problem. Hence what the character wants is actually a particular state of being. Such a state might mean being in a position of wealth, power or respect, or being in a happily ever after relationship. Cinderella wants merely to be free of her involuntary servitude, if only for a little while.

This makes the want distinct from the goal, which is the specific gateway to the wanted state of being, as perceived by the character. A story usually sets up a goal the character needs to reach or attain in order to achieve the want. In Cinderella’s case, it is attending the ball.

So, a story has its characters pursue their wants. These different wants oppose each other, causing conflicts of interest. The conflicting wants make the characters active, and the audience/readers like stories about actions, that is, about characters who do things.

Sounds simple.

And yet frequently stories seem to mess up on this vital point.

Next to passive characters without a strong enough want, lack of clear motivation is a huge writer trap. It is possible to write a whole story full of characters who are reactive instead of active, or who do things of their own volition but without that volition being clearly recognisable to the audience/reader. It is perhaps even tempting to write stories like that, because they seem more lifelike. In real life, people do not necessarily have distinct goals. Often, our wants are vague and not clearly definable. What about writing a realistic story about a character with a general sense of dissatisfaction, who, like so many of us, has lost sight of any clear objective in life?

It’s doable, certainly. But the audience/readers will probably start to look for the specific want of such a character. They would probably begin to expect the story to be about this character’s search for a clear objective in life. That might be the want the audience would tacitly ascribe to the character.

And if the story does not bear such motivation out, the risk is significant. Because stories in which the audience does not understand what the characters want lack emotional impact.

A way of adding psychological depth and emotional complexity to characters is to give them several and even contradictory wants. Gollum in Lord Of The Rings wants the ring. Yet a part of him also wants to give up the ring and help Frodo. Next to solving the case, Marty Hart in True Detective wants to be a good husband and family man, but he also wants affairs with other women. That’s three wants for one character.

A want is not merely a yearning, it is an expression of values. What a character desires shows the audience something about that character. In this sense, two contradictory wants provide the basis for a powerful scene of choice. At a crisis point, the character may face a dilemma and have to choose between two courses. Both might lead to some state the character desires, but these desires prove to be mutually exclusive. For the audience, which choice is the right one might be obvious – they will be rooting for the character to go one way. But for the character there may be a strong pull the other way. The final choice shows the character’s moral fibre – and often expresses the story’s theme.

Is it really always absolutely necessary for every character to have a clearly defined want?

Not entirely. Because, of course, there are exceptions.

In certain cases, the author might deliberately obfuscate the why of a character’s actions in order to inject mystery. Not knowing something keeps the audience/reader guessing and turning the pages or not switching the channel. Usually this mystery is cleared up at some point. The audience tends to expect that. Which implies that even if the want was not made clear to the audience early in the story, it was there in the character nonetheless – and certainly the author was aware of it.

Injecting mystery by keeping character motivations hidden is not in itself a writer trap. But nearly. When tempted to use such a device, an author should at least consider if it would not actually be more interesting for the audience to know the character’s motivation.

Having said that, there are rare cases where a character’s motivation does remain unexplained. And those cases can be powerful. Especially when it’s a baddy we don’t understand.

Think of Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello, who is simply bad to the bone and we’ll never really know why. Shakespeare – deliberately, one presumes – gives no hint as to what Iago hopes to achieve by ruining Othello. Shakespeare might easily have given Iago some clearly understandable motivation, such as revenge of a past wrong, envy of Othello’s success, desire to usurp Othello’s position, lust for Desdemona. But he didn’t. And Iago is one of the most superb villains ever.

Another possible exception are (fiction) memoirs in the first person, such as David Copperfield, The Catcher in the Rye, Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March, or William Boyd’s Any Human Heart. In such stories, the effect of the narrator telling his or her own story creates a disparity between the time of the story told and the implicit future time of the act of telling. The narrator is relating a past from the perspective of an older self. This older self has reached a state of being which is different from that of the character being told about – the narrator is wiser than his or her younger self. This creates an effect for the reader: the reader wants to know how the character reach this older, wiser state. With this device, it is possible to make character wants less obvious or direct and still maintain an emotional drive to the story.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about a character’s want is how it stands in conflict with what that character really needs.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Click to open a new story project:

So the old storytelling adage. What does that mean, exactly?

In this post, we’ll consider:

The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

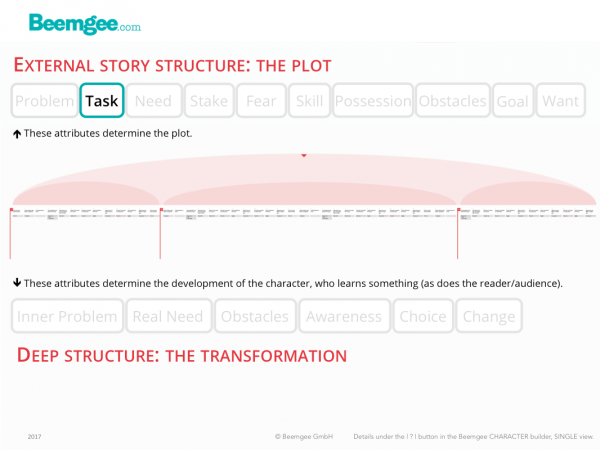

More or less explicitly, the main character of a story is likely to have some sort of task to complete. The task is generally the verb to the noun of the goal – rescue the princess, steal the diamond. The character thinks that by achieving the goal, he or she will get what they want, which is typically a state free of a problem the character is posed at the beginning of the story.

The action is what, specifically, the character does in order to achieve the goal (rescue the princess, steal the diamond). In many cases, this action takes place in a central scene. Central not only in importance, but central in the sense of being in the middle.

Let’s look at some examples. (more…)

The task is the more or less explicitly defined mission a character sets out on in order to reach the goal and thereby solve the external problem.

Many of the major characters in a story will have something to do, which may result in them getting in each other’s way.

Task as Function

In a story, more or less everyone has a task. What characters do in a story defines them and determines their roles and narrative functions in the story. In this sense, it is an antagonist’s task to get in the way of the protagonist; an ally’s task is to help the protagonist; a mentor’s task is to advise the protagonist and set them on their way.

But while all that is true, it isn’t really what we mean by task.

Task as Action

The characters’ actions make them who they are. To define a character’s task is to state clearly what that character has to achieve in the story. It is the action that leads to(more…)

Easy to spot McGuffins are the Ark of the Covenant in Raiders Of The Lost Ark, the statuette in The Maltese Falcon, private Ryan in Saving Private Ryan, the ring (more specifically, the act of its destruction) in Lord Of The Rings. Note how in these examples, the McGuffin is in the title of the story. The McGuffin is embedded in the narrative structure and becomes what the story is about, on the surface at least.

Typical genres that have McGuffins are comedy, crime, adventure, fantasy and other quest stories. But conceivably, a dressed up McGuffin might be found in any genre.

Nor does a McGuffin have to be an object. It could be a person or a quality. In a story of several characters vying for the love of one other character, that love might be considered the McGuffin. A place might become a McGuffin too – consider the role of the planet Earth in Battlestar Galactica.

In terms of narrative structure, a McGuffin occupies the(more…)

Convictions and beliefs are effectively values put into words. They lead to a rationalised intellectual stance and can be the basis for lifechoices and actions. A set of beliefs or convictions is the articulated version of a character’s values or emotional stance.

Consider story’s predisposition for cause and effect. If we understand the belief-system or intellectual stance as the effect, the value-set or emotional stance is the cause. Now, it may be nit-picking to make the distinction between felt values and stated beliefs. But then again, it might be quite helpful to see by what line of reasoning a character justifies his or her behaviour.

The effect can be powerful when there is a discrepancy (i.e. conflict) between what the character thinks is the reason for his or her actions and the real reason. When the audience or readers see that the words and thoughts of a character do not match with what that character is actually motivated by, the irony can be a satisfying story experience.

By emotional stance we mean a value-set. This is particularly important when one considers that often stories show value-sets in conflict. The protagonist and in particular the protagonist’s journey to recognition and change may represent certain values. These will be in direct contrast to the antagonist’s values. The theme of the story presents one value-set as preferable over the other.

In many stories, the protagonist starts out with a value-set that is warped or flawed. Their real need is to become aware that their value-set is harmful or negative, probably ultimately selfish, and find a way to gain new values that are more social, cooperative and selfless. For the purpose of such a story, the values are initially expressed in the internal problem and by the end have gone through a change.

Values do not emerge in a vacuum, they are instilled by environment or culture. Stories exhibit cause and effect, and the values of each of the characters are no exception. The audience looks for the causes of a character’s emotional stance. By the very nature of emotions and values, their causes can be hard to pinpoint – while at the same time being somewhat obvious. In stories, at least.

Furthermore, values are emotional and therefore exist before they are articulated. A character becomes conscious of a value-set in the form of a system of beliefs. The beliefs are articulated by the character as convictions, and are determined by inner values. In some cases, the stated beliefs may actually be in conflict with the character’s deeper values, of which the character may not be entirely aware. Values tend to feel right to the individual, though they may actually be wrong for the larger community or society.

A character’s values have to be plausible to the audience, which may be achieved for instance giving the characters appropriate social backgrounds or origins and making these explicit. In many stories, a character’s upbringing or their origin is named or described in order to explain their emotional stance.

Alternatively, values may be caused by certain specific events in the history or background of a character, conveyed as backstory in the narrative. A particular circumstance, possibly a trauma, leads the character to feel a certain way about life and the world.

In historical stories the time-setting is particularly challenging in terms of the emotional stance of the characters. Much popular historical fiction may justly be termed anachronistic in that it has characters – especially female protagonists! – exhibiting values and beliefs which do not fit into the time. For example: In the Middle Ages, the advent of humanism had not occurred yet. There had been no Renaissance, no Descartes, no Kant, no French Revolution and no American Constitution. Where is a character in the Middle Ages supposed to get ideas, values and convictions from that today we take for granted? Ideas about inalienable rights such as liberty and equality or concepts such as individualism. People in the past had different values and belief systems from people today, and it is almost impossible to put ourselves in their shoes. Historical fiction that does not at least implicitly deal with this challenging issue is more likely to be clichéd and trivial.

Which does not mean that trivial historical stories can’t be wildly entertaining with strong emotional impact. After all, modern stories address the audience of today. It means simply that an author usually has some sort of attitude to the issue.

Photo by Wonderlane on Unsplash

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Already using the author tool? If not, try it here:

Much of the craft behind fabulation has to do with structuring the story being told, the construction and organisation of its narrative. Many authors design this construction first, before filling the first page with text. The process of planning how the story works is known as outlining.

There are significant benefits to outlining. For one thing, going through this process usually entails fewer rewrites later. When the author knows the direction of the storyline, it is easier to keep all its threads under control while writing. Without this direction, there is a danger of losing the plot half way through.

Stories have structure. (more…)

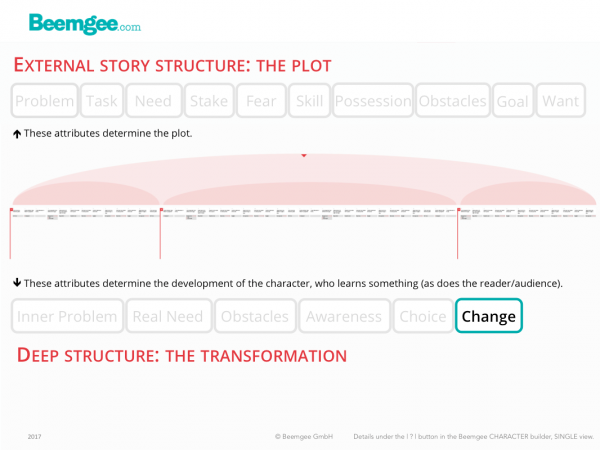

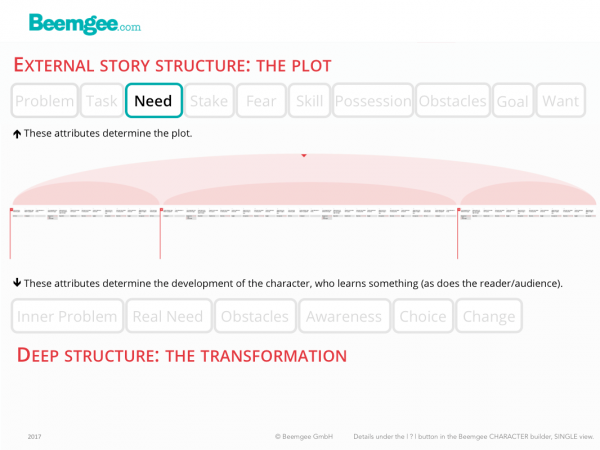

A story, pretty much by definition, describes a change. Indeed, every single scene does.

At the very least,

We have said before that a protagonist is usually wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. We have seen that this has something to do with the want, which – whether the character achieves it or not – is usually only attainable by causing a change. Often the change involves the character’s solving the internal problem, so the change takes place within the character. This involves the recognition of the necessity for change, i.e. the acceptance of the real need, and the struggle to achieve it. So all the incidents and events in the plot, the hindrances and obstacles the characters deal with, are in themselves not so very interesting. What interests the audience more is how these events and obstacles change the character.

Having said that, a story may well show no more change than the solving of an external problem. A story world is disturbed, but at the end returns to a similar state. For instance in a detective story, where the crime is solved but the protagonist does not really develop.

Characters don’t change in a vacuum. They learn through interactions with each other. Relationships cause change. In many stories, subplots will tell of the characters that surround the protagonist, and their changes and developments may well cast light on various aspects of the story’s theme. Or perhaps the story is an ensemble piece, where it is not easy (or even necessary) to identify a main protagonist. Or it is a romance, or buddy-story, which apparently has two main characters. Whichever – some level of change usually occurs in all the main characters as a result of how they interact with each other.

There is, by the way, one often neglected archetype who also typically changes. This role is sometimes referred to as foil. We call it the role of the contrastor. The contrastor mirrors and contrasts the protagonist, like Han Solo to Luke Skywalker in Star Wars or the mother to the boy in Boyhood.

Quite possibly, the entire story-world may be different by the end of the story than it was at the beginning. Story-world as a concept refers to the scope of the world presented in the story, so if the field of action of the characters is small, the story-world is small too. If the story is an epic, the story-world will be big, a version of an entire world.

As an aside on this last point, consider the classical genres. Epics – again, almost by definition – describe a change in a whole world. In a way, so does tragedy, for at the end of the tragedy the world will have lost one or more of its population, since tragedy deals with the change from life to death.

Comedy seeks to describe a different fundamental change in the story-world. The typical structure of comedy, whether we are talking about Aristophanes or modern TV sitcoms, has a stable situation at the beginning which is disturbed by some event or problem. The disturbance causes first a lot of messy but generally non-life-threatening chaos which is resolved by a return to the original undisturbed situation. Even if the main characters end up married, for example, the story-world is brought back to its stable state.

The very serious point of comedy is to demonstrate a fundamental truth: the cyclical nature of change in the universe. Spring always returns, no matter how bleak the winter. Day always comes, no matter how dark the night. Change does not have to be final. Change can be cyclical. Change is life.

The most fundamental change that stories tend to describe is one of recognition of truth. What is not known at the beginning of the story is recognised and thus becomes known at the end. This is obvious in crime stories, but holds true for almost all other stories too. The story therefore amounts to an act of learning. Often the learning curve is observable in the protagonist, who tends to be wiser at the end than at the beginning.

But the point is really that the recipient, the reader or viewer, is actually the one doing the learning – through experiencing the story.

The audience changes.

At least, that’s the general idea. The story provides a physical, emotional and intellectual experience – physical when your heart beats faster or your palms sweat, emotional when you feel for the characters, and perhaps intellectual too if the story gives you pause for thought. If the story achieves none of these responses, then it has failed. An experience, again pretty much by definition, changes you. We learn through experience; so if you have changed, chances are it’s because you have learnt something.

Hence it is not only within the story that a change takes place. It takes place outside of the story as well, in the recipient.

Within some stories one may argue that no real change occurs – Alice does not obviously change due to her experience in Wonderland. But the reader has been taken on a wild journey, and the experience is likely to have left some sort of mark.

How does a story provide an experience?

By allowing the recipient, the audience or reader, to understand and feel change and transformation throughout the story. Every scene describes a change. The entire narrative shows a difference between the “before and after”. Stories have a tendency to symmetry: The beginning of the story makes clear what the state of the protagonist or the story world is before the story journey commences, and the end of the story has a corresponding scene or event that shows what the state is after.

For the author, then, the task is to clearly know the state of things for the protagonist, the cast of characters, the story world, and the audience at the end of the tale, and the state of things at the beginning of the tale. The greater the contrast, the better. Once these two points of reference are known, the author works out the many steps needed to get the protagonist, the cast of characters, the story world, and the audience from one state to the other.

There is a paradox here. The change that occurs is also an expression of new equilibrium. At a very basic level, story structure can be described as follows:

So change is all-pervasive in stories, within them in the form of character development, and without in the form of audience understanding. And that is not even to consider the transformational power of telling a story, when the act of telling the story brings about change in the author.

Read here how change is important for every single scene, though we prefer to call them plot events.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Not developing your story yet? Click here:

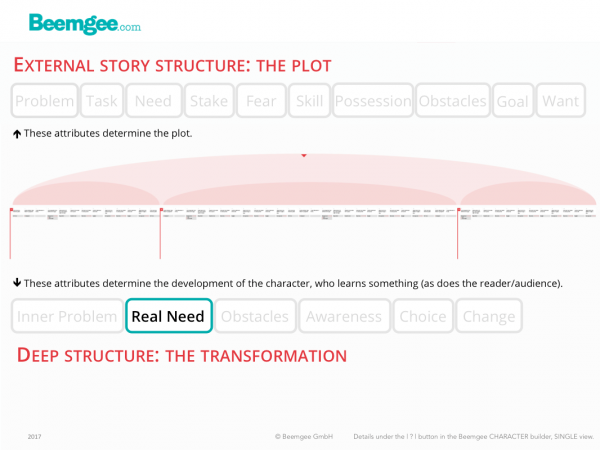

Characters display flaws or shortcomings near the beginning of the story as well as wants. What they really need to do in order to achieve what they want is likely to be something they need to become aware of first.

The real need relates to the internal problem in the same way the perceived need relates to the external problem. The character has some sort of dysfunction that really needs to be repaired.

That means the audience or reader may become aware of a character’s real need long before the character does. Most stories are about learning, and learning entails the uncovering of something previously unknown. So the real need of a character is to uncover the internal problem, to become aware of their flaw.

A character may be unaware of their real need because they are suppressing a secret from their past. Something they did (better than something that happened to them) causes shame or guilt and they therefore hide it from themselves. To get over this, they must achieve some sort of healing. The trick is to dramatise such inner conflict through plot events.

To recap: The usual mode in storytelling has a character consciously responding to an external problem with a want, a goal, and a number of perceived needs. Unconsciously, that character may well have a character trait that amounts to an internal problem, out of which arises that character’s real need – i.e. to solve the internal problem.

So if a character is selfish, the real need is to learn selflessness. If the character is overly proud, then he or she needs to gain some humility. In the movie Chef, the father neglects his son emotionally – his real need is to learn to involve the child in his own life. The audience sees this way before the Chef does.

Even stories in which the external problem provides the entertainment – and with that the raison d’être of the story – may profit from(more…)

The outward needs of a character – things she needs to acquire or achieve in order to reach the goal – divide the story journey into stages.

In storytelling, characters usually know they have a problem and there is usually something they want. They tend to set themselves a goal which they believe will solve their problem and get them what they want.

In order to get to the goal, the character will need something. Some examples: If the goal is a place, a means of transportation is necessary to get there. If we can’t rob the bank alone, we’ll have to persuade some allies to join our heist. If the goal is defeating a dragon, then some weapons would be helpful. If magic is needed, we’ll have to visit the magician to pick some up.

While the perceived need might be an object or a person, it usually requires an action. We’ll need a car, so do we buy one or steal one? We’ll need a sword, so do we pull one out of a stone or go to the blacksmith? If we need help, who do we ask and how do we talk them into joining us? We’ll need magic, but how do we find a magician? Ask an elf or go to the oracle for advice?

So, once the goal is set, a vision of the way to reach it opens up to the protagonist – and with that to the audience/reader. At the very least, the first step of the way presents itself. All this is what the character is conscious of.

In other words, the character forms a plan.

The plan is communicated more or less explicitly to the audience. The anticipation of how things will not go quite according to plan is part of the pleasure. There must always be surprises in store for the characters as well as for the audience.

The perceived needs are (more…)

To be fair, this question is a relatively new one for authors to ponder. In the pre-modern age, authors just grabbed their quills and started writing. But as novels became more sophisticated, technical questions became more explicit and relevant. Narrative voice – the matter of who is talking here, or what is this text we’re reading purporting to be – is a factor at the latest since James Joyce’ Ulysses and all the self-aware post-modern novels that followed. Previously, there had already been a difference between author and narrator. When in a novel by Charles Dickens you, dear reader, are directly addressed, then already there is some sort of discrepancy between the person saying “dear reader” to you and Charley Dickens the man. But this discrepancy didn’t become a popular topic to construct stories around until the twentieth century.

Anyway, while not a traditional archetype, and in many cases not even a participating character, the narrator is never really quite the same entity as the author either.

To begin with the basics, the standard narrator types are:

In film, first person and third-person limited effectively amount to the same thing: the audience gets one person’s perspective on the story per shot or scene (there is also the first-person “point of view” camera angle, but rarely is an entire film presented that way). In prose, first and third person is the difference between “I did this” and “she (or he) did that”. This is a stylistic choice. In the sense of what the narrator knows and tells, there is not necessarily much difference.

But potentially there is big difference between narrative stance. A narrator who is limited to reporting in third person on only one character can do so “close” or “from a distance”.(more…)

In storytelling, discrepancy between a character’s awareness and the awareness-levels of others is one of the most powerful devices an author can use. “Others” refers here not just to other characters, but to the narrator and – most significantly – to the audience/reader.

Let’s sum up potential differences in knowledge or awareness:

In this post, we’ll concentrate on the first point: Awareness of the internal problem. We’ll break that down into

Becoming Aware – the importance of the revelation (more…)

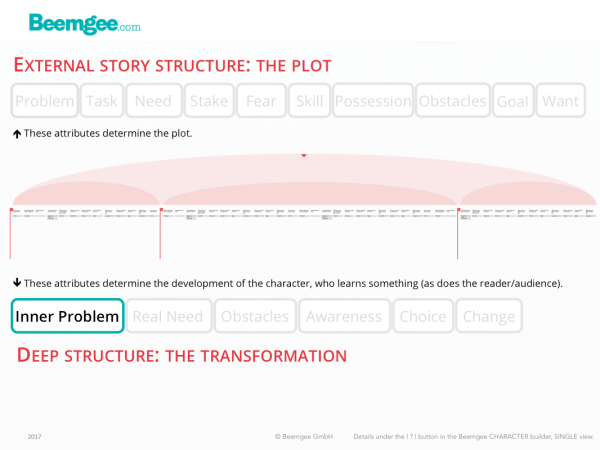

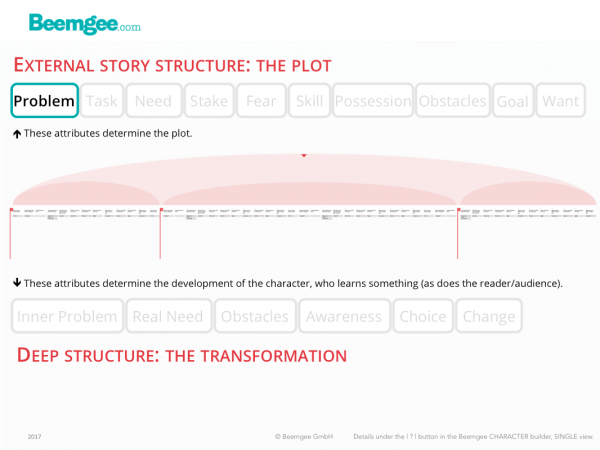

While the external problem shows the audience the character’s motivation to act (he or she wants to solve the problem), it is the internal problem that gives the character depth.

In storytelling, the internal problem is a character’s weakness, flaw, lack, shortcoming, failure, dysfunction, error, miscalculation, unresolved issue, or mistake. It is often manifested to the audience through a negative character trait. Classically, this flaw may be one of excess, such as too much pride. Almost always, the internal problem involves egoism. By overcoming it, the character will be wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. Thus the character must learn cooperative behaviour in order to be a mature, socially functioning person.

The inner problem is the pre-condition for the character’s transformation. It is the flaw, weakness, mistake, error, or deficit that needs to be fixed. In other words, it shows what the character needs to learn.

Internal problems may be character traits that cause harm or hurt to others. They cause anti-social behaviour. And internal problems can also harm the character. They can be detrimental to his or her solving the external problem.

From Lack of Awareness to Revelation

While the external problem provides a character’s want, i.e. motivation, the internal problem provides the need.

The audience sees the flaw before the character does. The character is blinkered, has a blind spot. She first has to learn to see what the audience already knows. (more…)

Problems come in all shapes and sizes. What’s more, in storytelling they come from within and without. The problems that come from within are hidden, internal, and it is quite possible for a character not to be aware of them. They are typically character flaws or shortcomings.

But they are not usually what gets the story going. Most stories begin with the protagonist being confronted with an external problem.

The external problem of the main character triggers the plot. It is shown to the audience as the incident which eventually incites the protagonist to action.

In some genres this is easy to see. In crime or mystery fiction, the external problem is almost by definition the crime or mystery that the protagonist has to deal with.(more…)

With a well-rounded cast of characters, the plot will almost take care of itself. A story gets energy from the dynamic that occurs between the all the characters in it. The interaction between the characters is fueled by contrast, motivations, and conflict. Put a bunch of characters in a room – i.e. on a stage, between the covers of a book, between the first and last shots of a movie – and the plot is likely to emerge on its own. As long as there are contrasts between the characters and their motivations, conflict will arise.

So how does an author cast the characters that bring the story to life?

First of all, one character is rarely enough. Almost all stories need several characters. Even Robinson Crusoe couldn’t hold out alone. It’s the interplay between characters that creates interest. For interplay, read conflict.

Conflict in storytelling does not mean fights and battles. It means a conflict of interests.

Characters become characters because they have interests. Their interests make them do what they do, and this doing is what drives the plot.

What does that mean?

It means characters are motivated. They(more…)

To state its theme is one way of describing what a story is about. To start finding a story’s theme, see if there is a more or less generic concept that fits, like “reform”, “racism”, “good vs. evil”. The theme of Shakespeare’s Othello is jealousy.

Once this broadest sense of theme is established, you could get a little more specific.

The theme is the expression of the reason why THIS story MUST be told! The theme of a story holds it together and expresses its values.

Theme may therefore be seen as an implicit message. But make sure that the message remains implicit, allowing the audience to understand it through their own interpretation.

Since a theme is usually (though not always) consciously posited by the author, it has some elements of a unique and personal vision of what is the best way to live. At best, this is expressed through the structure of the story, for instance by having the narrative culminate in a choice the protagonist has to make. The choices represent versions of what might be considered ways to live, or what is “right”.

But beware! This is a potential writer trap. See below.

How story expresses theme

Theme is expressed, essentially, through the audience’s reaction to how the characters grow. A consciously chosen theme seeks to convey a proposition that has the potential to be universally valid. Usually – and this is interesting in its evolutionary ramifications – the theme conveys a sense of the way a group or society can live together successfully.(more…)

While plots may be “archetypal” when they exhibit certain forms, in this post we are concerned with character archetypes.

In modern storytelling, to consider them as archetypes might suggest a bit of a corset, perhaps even a straightjacket for the characters. For today’s author, to present a character as an archetype does not seem conducive to achieving psychological verisimilitude.

But an archetype is not the same as a stereotype. An advisor or mentor does not need to be a wise old man like Obi-Wan Kenobi. And an antagonist does not need to be a baddy.

Consider archetypes as powers within a story. Like planets in a solar system, they have gravity and they therefore exert force as they move.

Archetypes denote certain general roles or functions for characters within the system of the story. There is ample room for variation within each role or function. Boundaries between one archetype and another may be fuzzy. And it is possible for one character to stand for more than one archetype.

Archetypes Through The Ages

In storytelling, people use the term Point of View (or PoV) to refer to different things. We’ve narrowed it down to four definitions:

The entire Star Wars saga is, in very general terms, told from the point of view of the two characters that have least status: the robots C-3PO and R2-D2. They are not present in every single scene, but they are part of the overall course of events – and in a ironic tip of the hat to their function of providers of overall point of view, George Lucas has C-3PO relate the entire story so far to the Ewoks in Return of the Jedi.

George Lucas borrowed the idea from Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress, which tells a story of generals and princesses from the point of view of two peasants. These two are involved in the action, but understand less about what they see going on than the audience does.(more…)

In the beginning, before audience or readers are emotionally involved and concerned about the fates of the characters, the danger of them turning away from the story is greatest.

Now, there’s more to a beginning than the kick-off event. While being an attention grabber, the entire first section of a story also has to establish the following:

That sounds self-evident, but all the elements needed to answer those three points amount to an awful lot of information. And at this stage, the audience or readers are not yet patient or forgiving, because they are not yet emotionally hooked.

In this post we will:

Who/what/where

Narrative is the choice of which events to relate and in what order to relate them – so it is a representation or specific manifestation of the story, rather than the story itself. The easy way to remember the difference between story and narrative is to reshuffle the order of events. A new event order means you have a new narrative of the same story.

Narrative turns story into information, or better, into knowledge for the recipient (the audience or reader). Each story event is a unit of knowledge the audience requires.

A narrative is paradox, because it seeks to convey truth by hiding it. A storyteller arranges the items of knowledge in such a way that they are revealed gradually, which implies initially obscuring the truth behind what is told. Such deliberate authorial obfuscation creates a sense of mystery or tension, and creates a desire in the audience to find out what is happening in the story and why. In this sense, a narrative is effectively the opposite of an account or a report.

A report presents information in order to be understood by the audience immediately, as it is being related. A neutral, matter of fact presentation probably maintains a chronology of events. It explains a state of affairs blow by blow, and aims for maximum clarity at every stage. It seeks to convey truth by simply telling it. While the point of a narrative is also that the recipient perceives the truth of the story, in a narrative this truth is conveyed indirectly. Narrative is therefore responsible for how the recipient perceives the story.

In this article we’ll look at

First, let’s state some basics as we understand them here at Beemgee: a story consists of events that are related by a narrator; events consist of actions carried out by characters; characters are motivated, they have reasons for the things they do; there is conflict involved; one and the same story may be told in different ways, that is, have varying narratives.

Note that we are talking here about narrative in the dramaturgical sense – not in the social sense. Like the term “storytelling”, the word “narrative” has become a bit of a buzzword. We are not referring here to open “social narratives” such as “the American narrative”. For the definition and exploration of such collective narratives, see our article in The Bigger ‘Narratives’ of Society. Here, we are pinpointing the use of the term primarily for storytellers creating novels, films, plays, and the like. Such works tend in their archetypal form to be closed narratives with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

A narrative may present the events of the story in linear, that is to say chronological order or not. But the story remains the story – even if it is told backwards.(more…)

Narrative is the order in which the author presents a story’s events to the recipient, i.e. the audience or reader. Chronology is the order of these events consecutively in time. Some people use terms from Russian Formalism, Syuzhet and Fabula, to make the distinction.

A chronology usually has less emotional impact than a narrative – essentially a chronology is recounting a report whereas a narrative is telling a story. In a chronology, the plot events are lined up in temporal sequence. You could say “and then” between each event. In a narrative, the emotional effect is closely related to the causality implied by the arrangement of the events. Between each event you could say, “because of that …”.

Narrative therefore carries with it the implication of understanding. The juxtaposition of events, for example, will create associations in the audience’ minds that lead to possibilities of interpretation. While a chronology may explain things, it is in itself inherently neutral. Narrative on the other hand is an arrangement that is usually consciously made by an author who intends something by the particular arrangement, and which, independently of author intention, is subject to interpretation by recipients.

While the convention in most storytelling is linear, i.e. to relate the story’s events consecutively in time (chronologically), we as audiences and storytellers are also very used to narratives that move certain events around. An event may be moved forward, meaning towards the beginning of the narrative, perhaps even to be used as a kick-off. Or possibly events may be withheld from the audience or reader and pushed towards the end, perhaps to create a reveal late in the narrative for a surprise effect – though this technique often feels cheap. Also, an author may use flashbacks to insert backstory events from the past, the past being all relevant events that take place before scene one in the narrative.

As authors, when we begin composing a story, we(more…)

We’ll talk here about describing events, since the usual term scene is more general and has different meanings for different media. Furthermore, a scene may conceivably contain more or less than one entire event.

An event in a story requires three elements: characters, function, and (perhaps most importantly) a difference between expectation and result.

In describing each plot event, it is useful to consider the six wh- questions as a guide: Who does what to whom, where, when and why? With this approach, each plot event gains its own logline, which is a good exercise since it forces you as an author to figure out just what dramatic function each plot event has in the context of the overall narrative.

Viewing the overall narrative, certain plot events can function as beats. More on this structural function of plot events here.

Characters causing events make story. As(more…)

Do you really consciously control what comes out of your fingers onto the page?

Even when writing happens “naturally”, while the words are pouring forth, the author is probably already performing a first level check that precedes the more detached and critical control of rewriting. If you want to make yourself more conscious of this process, consider putting an imaginary parrot on your shoulder every time you sit down to write.

![]() A parrot?

A parrot?

Well, the creature of your choice. At Beemgee, it’s a parrot.

The parrot reads what you write as you write it and squawks a running commentary into your ear. It might commend a good sentence or it might censure. It might suggest alternative words or phrases. It may like or hate a paragraph.

The parrot has three main hobbyhorses: relevance, surprise, and recognition.

Relevance – (more…)

If you’re thinking about composing a story, you will probably have some characters in mind that will be performing the action of the story. In stories, action and actors (in the sense of someone who does something) are pretty much the same thing looked at from two differing perspectives, as we have noted in our post Plot vs. Character.

The most obvious difference between characters in stories and people in real life is that story characters tend to be driven. Narratives tend to be more compelling when the characters they describe are highly motivated. Rarely in life are our wants, goals, and perceived needs as clear and powerful as for characters in stories. Our real lives tend to drift rather than head in a specific direction; it is often in retrospect that we ascribe direction when we try to understand our lives by putting them into narratives. Historical personages who seem to demonstrate drive and direction (and have perhaps become historical personages because they had these qualities) make for more interesting biographies than people whose motivations were less strong.

Another aspect that sets characters in fiction apart from people in life is that characters tend to fulfil narrative functions in their story. People, on the other hand, live their lives by acting naturally according to the dictates of their personality. A story is a more or less enclosed unity, while an individual’s life is part of a greater whole. Only in retrospect do we sometimes overlay a narrative onto the biography of an individual – because we tend to feel happier when we perceive structure or direction in the lives of others or indeed our own. We can extract more meaning out of a life that can be told with structure and direction. In fact, there is no way of recounting a person’s biography without making choices concerning structure. If we’re honest, even the choice of which events to relate and how to relate them injects a fair amount of fiction into the story of a life, especially when that life is our own as we tell it to others or ourselves.

Many stories focus primarily on one protagonist. In fiction at least, the protagonist is often wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. The(more…)

For some people, plot is like a dirty word. They prefer their stories to concentrate on character. Or premise. Or language. It is action movies or thrillers by Michael Crichton or Robert Ludlum that have plots.

At Beemgee, we believe that the four pillars that hold a story up are plot, character, meaning, and language – with conflict as girders. Every story, no matter how “good” or “bad”, exhibits all four of these pillars. No story can really go without any one of them. Not to mentions aspects like story world, backstory, or exposition.

We have not found a single work of fiction in any medium or genre that does not have a plot. Ulysses has a plot. The Sound And The Fury has a plot. Even some of the most famous attempts in literary history to shun plot, such as I Am a Cat by Soseki Natsume or Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne, did not manage to avoid describing events and characters. Their language might be beautiful and to an extent their premise is the attempt to shun plot. But nonetheless, the stories describe events, things happen in an order, the authors made conscious decisions about the sequence in which to relate the occurrences. To what degree the narrative is structured in these books may be topic for debate, but if we consider plot to be simply a sequence of events, then no story can go entirely without it and still be considered a story.

There is an intimate relationship(more…)

That is, next to impossible.

Backstory is the stuff that went on before the story begins, or more precisely, before the kick-off event in scene 1. As such, backstory might better be called “pre-story”. It is a necessary component of any story.

After all, the characters come from somewhere – they have pasts, they have histories. These histories have shaped them into who they are, which determines their actions now, in the time of the story. These actions are the source of the events of the story. So some part of the characters’ histories will be relevant to the story – and this bit of information or knowledge needs to be passed on to the audience or reader. That’s why so many stories have “campfire scenes”, a moment of calm usually near the beginning of the second half during which characters recount stories of their pasts to each other. (more…)

One recognizable convention from film is what we might call the kick-off event. It is the opening scene, the very first item in the narrative. This is not to be confused with the inciting incident.

We’ll refer to the kick-off event as the initial scene, and whatever the medium – page, stage, or screen – it ought to capture the audience’s or reader’s attention.

The kick-off event can be drawn from virtually anywhere in the event chronology – like a “capsule” of plot pulled out from the narrative (more on that below). It may open up some questions to arouse our curiosity, or tell us something about a major character that will become relevant much later. It can throw the audience or reader, the recipient of the story, in medias res, straight into the middle of an exciting event. Or it can build up slowly to set the scene and establish a mood.

This first event(more…)

We look for the person or thing responsible for any action or phenomena we experience; we seek to ascribe “agency” to what we perceive. What this means is that when we notice that something happened, we tend to look for the cause of the event. This probably has a simple evolutionary explanation. If we hear a rustle in the bush behind us, we immediately turn around to see what moved. This reflex is a safety mechanism to detect threats. Before homo sapiens lived in houses, the individuals for whom this reflex worked most efficiently probably lived longer, and thus had better chances of passing on their genes. The point is, we assume that something or someone caused the phenomenon (the rustle) and seek to attribute it to an agent. If we are sitting in our living room and hear a floorboard creak in the hall, we would want to know what caused it too.

This safety mechanism has all sorts of ramifications. It influences(more…)