Real Need: the Emotional Need of a Character

In most stories, what a character really needs is growth.

Characters display flaws or shortcomings near the beginning of the story as well as wants. What they really need to do in order to achieve what they want is likely to be something they need to become aware of first.

The real need relates to the internal problem in the same way the perceived need relates to the external problem. The character has some sort of dysfunction that really needs to be repaired.

That means the audience or reader may become aware of a character’s real need long before the character does. Most stories are about learning, and learning entails the uncovering of something previously unknown. So the real need of a character is to uncover the internal problem, to become aware of their flaw.

A character may be unaware of their real need because they are suppressing a secret from their past. Something they did (better than something that happened to them) causes shame or guilt and they therefore hide it from themselves. To get over this, they must achieve some sort of healing. The trick is to dramatise such inner conflict through plot events.

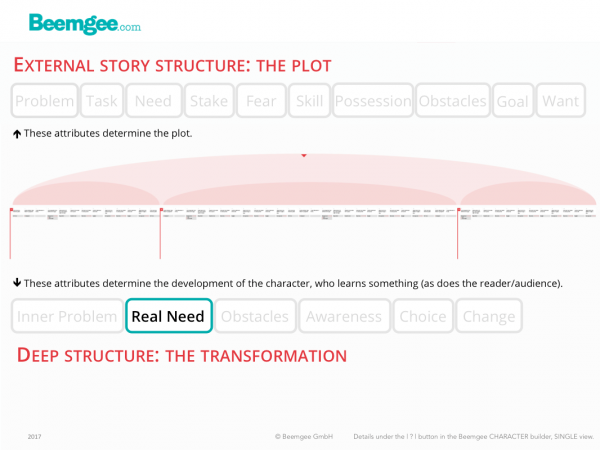

To recap: The usual mode in storytelling has a character consciously responding to an external problem with a want, a goal, and a number of perceived needs. Unconsciously, that character may well have a character trait that amounts to an internal problem, out of which arises that character’s real need – i.e. to solve the internal problem.

So if a character is selfish, the real need is to learn selflessness. If the character is overly proud, then he or she needs to gain some humility. In the movie Chef, the father neglects his son emotionally – his real need is to learn to involve the child in his own life. The audience sees this way before the Chef does.

Even stories in which the external problem provides the entertainment – and with that the raison d’être of the story – may profit from a sub-layer of internal problem and real need. It is not vital to enjoying Raiders Of The Lost Ark, but notice how at the beginning of the story, Indiana Jones fervently believes the obstacles to his gaining the treasures he seeks are due to mechanical trickery (“hocus pocus”), whereas at the end he recognises that there are indeed spiritual powers beyond his secular world-view (“Don’t look!”).

Revelation

There is a strong connection, then, between the real need and self-revelation. If a character must repair a fault in his or her character, the fault must first be recognised. Often this occurs at the midpoint and is typically acted upon just before the goal – indeed the act of learning to accept the real need might make the goal redundant. The character makes amends for the fault – in the above examples, through an act of selflessness or by being humble – and as a reward gets what he or she wants, often not via the goal but by a route the character had at the beginning of the story not foreseen. Of course not, because the character at the beginning of the story had not recognised the internal problem and therefore could not know his or her real need. By the very end of the story, the character has grown. The real need is no longer there.

This is all neat, satisfying – and often conventional. We all know popular novels and Hollywood films that work this way. Which is absolutely fair enough.

But writer trap: Self-revelation with immediately positive results can quickly seem like a cliché. The technique seems to lead too easily to the happily-ever-after, and has inherent dangers like moralising. Heavy-handed use of the real need may lead an author to ascribe simplistic psychological causes to what the audience or reader is intended to perceive as a character flaw. Sidney Lumet describes such an obvious or clumsy backstory trauma as ‘the rubber ducky’ moment, when a character lost their rubber ducky during childhood and that is presented as the reason for their shortcomings.

There are Alternative Needs

For instance, it might make for a good story if the character is not able to get what he or she really needs. In stories that do not end quite so happily-ever-after, there is often a scene that corresponds to the self-revelation or the crisis moment of choice. It is when the audience or reader recognizes that the character will not get what he or she really needs. Often this audience epiphany must be provided by another character’s act of recognition, as in The Godfather, where Michael’s wife Kay has the door shut in her face, and she provides the point of view. In that moment, she realizes – and her face shows it to the viewers – that Michael has not been able to achieve his need, the need to escape from the family business. Quite the contrary.

Another way of avoiding the self-revelation writer trap is by basing the internal problem on a mistake rather than on a character flaw. Note that a mistake is something the character did, so it is active, rather than a trauma, which is often caused by something that happened to the character, and is therefore passive. If something the character did once upon a time (i.e. in the backstory) resulted in the current mess (i.e. the external problem), the real need may well involve recognition of this past act as having been a mistake. But there may be nothing the character can do about it now. If the character once made a mistake, it’s up to the gods and the author whether any atonement will bring redemption. May ancient classics hinge on mistakes, such as the story of Oedipus Rex.

And indeed, who says the character wants to be redeemed? Perhaps such a character will happily continue in their incorrigible way, and burrow him or herself into our collective consciousness as an unforgettable fictional character. Not every character must grow in order to be memorable. In cases where fictional characters do not change and grow, it is usually us, the readers or audience, that do the growing. Such characters tend to be revealed slowly, in stages, so that while they have not altered, our perception of them has, because by the end of the story we know more about them than at the beginning, and thus we have learnt something about ourselves. Consider Ishmael and Ahab in Moby Dick.

And finally, there is a form of need that provides a) an impetus for the character’s behaviour, and b) a reason for the audience to care. What a character cares about makes us care for the character. When a protagonist reacts emotionally to a circumstance, we see that this character has an inner life, and therefore relate to this character on an emotional level. For example, in Aliens, the second movie in the franchise, Ripley has been persuaded to return to the planet on which her crew originally found the nasty beast because the planet has since been colonised by ‘terraformers’ and there has been no signal from the colony for a while. The plot is well underway and Ripley and the rescue mission have discovered that the colony is ruined and there are now very many aliens there. Then Ripley finds a survivor, a young girl who calls herself Newt. From that point on, it is more than just a matter of survival for our heroine Ripley. She now has the emotional need to protect and rescue this child. That gives the narrative drive of the story a huge boost – now it is more important still to the audience that Ripley succeed, because she has to save Newt. It is implied that the real reason for Ripley’s emotional connection to Newt is due to a backstory concerning the loss of her own child, and the implication alone is more powerful than a complete explanation. The audience feels it, but how aware Ripley is of this cause for her feelings towards Newt remains unstated.

In any case, an emotional need in a main character provides some level of deeper psychological, emotional or moral meaning below the surface structure of plot. So this real need of a character provides a basis for a story’s “deep structure”, and tends to bring on the change that forms the emotional core of the story.

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer