A Brief Guide to Storytelling Essentials

How narrative structure turns a story into an emotional experience.

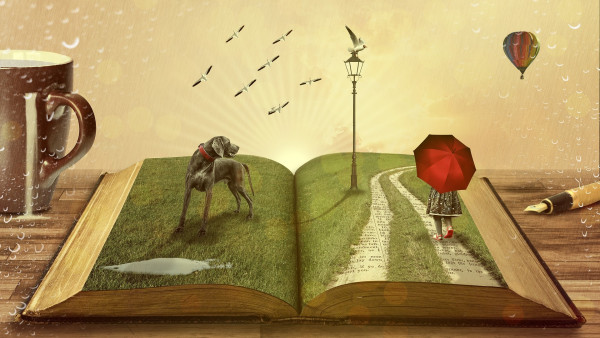

Image: Comfreak, Pixabay

Storytelling is a bit of an overused buzzword. While we are all – by dint of being human – storytellers, how aware are you of the principles of dramaturgy? What exactly constitutes a story, in comparison to, say, a report or an anecdote?

And just to be clear, the following is not a story. It’s an how-to article.

Whatever the medium – film or text, online or offline –, storytelling has something to do with emotionally engaging an audience, that much seems clear. So is a picture of a cute puppy a story? Hardly.

Stories exist in order to create a difference in their audience. Stories always address problems and tend to convey the benefits of co-operative behaviour.

While there simply is no blueprint to how stories work, let’s examine the elements that recur in stories and try to find some patterns.

Who is the story about?

All stories are about someone. That someone does not have to be a person, it can be an animal (Bambi) or a robot (Wall-e). But a story needs a character. In fact, all stories have more than one character, with virtually no exceptions. This is because the interaction between several characters provides motivation, conflict and action.

Moreover, stories usually have a main character, the figure that the story seems to be principally about – the protagonist. It is not always obvious why one character is the protagonist rather than another. Is she simply the most heroic? Is she the one that develops most? Or does she just have the most scenes? If the protagonist is the character the audience identifies with best, does that mean that she is the one most similar to the audience? Then what about American Psycho, or stories that are successful across cultural or temporal boundaries? How similar are you to the ancient Greek hero Hercules?

Even more tricky to pin down is the concept of the antagonist. This is the central opponent of the protagonist, who actively seeks to thwart our heroine. It’s worth remembering that the concept of the “baddy”, along with the idea that heroes and heroines are good and fight against villains who are bad, is not inherent to storytelling. The Greek myths, for example, do not feature goodies versus baddies. Rather, Greek heroes have moments when they do bad things. Hercules even killed his wife and children. How’s that for antagonistic?

So it helps to think of antagonism as a force, a power within the story, rather than necessarily as an evil character. And here is an important takeaway: the clearer and stronger the antagonism in your story, the more powerfully your protagonist will engage your audience emotionally.

Spoiler alert! WHAT stories are really about

To jump ahead (spoiler alert!): Every story shows change. If the protagonist or the situation (the world in which the story is set) has not changed by the end of the story from how the audience perceived it at the beginning of the narration, then there is no story. Change is a defining characteristic of stories.

Change requires development, the process of turning from one state to another. There are usually key moments in the narrative that mark stages of this development, the most important having to do with degrees of awareness.

Hence protagonists tend to develop in stories. How or why? To keep it short, in order to learn. On the whole, in most any story you can think of, the main character will be wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. She has learnt something. She has gained awareness.

Usually the qualities the character has learnt demonstrate that the co-operative principle of interaction between people is more likely to be successful. That’s one reason the goodies tend to win – the baddies are selfish; and the heroine overcoming her own selfish impulses leads to her achieving what she wants.

“Now wait a minute!”, we hear you cry. What about those stories in which the protagonist is not wiser at the end, has either not changed or indeed has changed for the worse?

In such stories the point tends to be that the audience recognises this lack or fault in the protagonist. The audience does the changing.

While composing a story it is easy to forget that the real point of ANY story is not just to show a protagonist learning, it is that the audience learns.

Characters, change, learning – What else?

Okay, so a story must have characters with problems who learn something and thereby develop and change. All this brings about that the audience has an emotional response. What else?

The more you think about a story as a sequence of events, the narrative chain that is the plot, the more you may realise that each plot event comes about due to specific character motivations. So whether your character is a victim, hero, or antihero, it pays to think deeply about the factors that determine the character’s motivation.

Developing the characters is key for conceiving a compelling story, because the characters’ motivations determine their actions, and these form the plot. Take the time to determine and understand your characters motivations!

And don’t forget that the audience has to care about them! Make them human, which means not too perfect and not too flawed. Think up a specific scene which is designed to show the character as someone worthy of the audience’ attention – and later worry. Then make sure that there is something at stake for this character, meaning the character has something important to lose if she fails to reach her objective.

More ingredients

So, to cut a long story short, here is a list of ingredients for a powerful story:

- Characters

- Problems

- Motivations

- Stake

- Conflict

- Actions

- Development

- Revelation

- Learning

- Change

We could say much about each of these concepts. To keep it brief, let’s concentrate on the most important point of all, the revelation.

We’ve implied revelation already, every time we mentioned recognition and awareness. To solve a problem, you first have to recognise it. Becoming aware of a solution is a form of revelation. To set up the revelation effect in a story, you need a couple of way stations in the plot.

You first determine a character and find her problem. Then you develop the character. For instance you must make clear to the audience what this character wants! A clear character-want makes it so much easier for the audience to emotionally engage with that character – so be sure your protagonist’s yearning is absolutely explicit!

Character development determines their actions, the things the characters in the story do (because, for example, they want something). These actions form the plot – the chain of plot events forms the narrative.

The narrative is designed to highlight the development. It therefore leads to a point of revelation. The effect is easiest to see in crime fiction, where the whole story leads up to the big reveal of the “whodunit”.

As we said earlier, the real revelation takes place in the audience! That means, when you are composing your narrative, think about the scene which will be the penny-dropping “aha-moment” for your audience.

Wrap the story up by making clear what it is you intend the audience to learn through this story, either by showing how the protagonist has learnt it, or by conceiving the story in such a way that the audience can nod their heads and think, “yeah, I got it!”.

The Whole Story

Three more concepts are extremely important for creating a story with emotional impact:

- Symmetry

- Cause and Effect

- The double layer of plot and transformation

1. Symmetry

Much overlooked is the phenomenon that enduring stories exhibit a tendency to symmetry. The end mirrors the beginning. Actually much more than that – in the middle is a pivotal event. Every scene after the middle might have a corresponding scene in the first half.

This structural precept connects closely with the technique of planting or foreshadowing, otherwise known as creating set-ups and pay-offs. A similar idea is expressed in the notion of Chekhov’s Gun.

2. Cause and Effect

Unlike in real life, in great stories every event is visibly und understandably the effect of a preceding event. The scenes are linked by causal connections. Describing a report or chronology you might say events are linked like this, “And then this happened, and then that happened”. But in a narrative, the events are linked for reasons, “Because of that, this happened, and because of that, something else happened.”

3. The Double Layer

The surface layer is the plot. This is built dramaturgically on what the character WANTs, what goal is set, what is needed in order to continue the journey towards that goal. It’s all about the task or mission, and what the characters DO.

The deeper layer concerns the character’s NEED, what their internal problem is, when they recognise it, and how they change as a result of learning this new sense of awareness.

Capture your audience’ attention by all means (for instance with a picture of a cute puppy), and then tell them a story. Stories that engage audiences emotionally …

- show a protagonist’s world (the setting) and a problem,

- define motivations such as a want as well as an opposing antagonism,

- feature a causal sequence of actions leading to clearly defined points of revelation,

- convey a transformational development which ends in your audience having learnt something,

- in the best case cause the audience to experience a change within themselves.

After you’ve gone to all that effort to tell your audience your story, reward them with a satisfying end.

Protagonists

So to get more practical, how does all this apply to charities and non-profits?

The reason a non-profit organisation wants to tell stories is likely to be to raise awareness for a particular issue or problem and awaken the desire in the audience to do something about it – or most probably help the organisation do something about it, for instance by donating money to it.

So the organisation has essentially these types of protagonist to choose from:

- A victim of an injustice – a person who suffers due to a problem the organisation seeks to address. Example: Oxfam or Unicef show a drought, famine or war victim.

- The helper in the field – a person from the organisation actively doing something to right a wrong. Example: Doctors Without Borders practicing medicine in areas without health care infrastructure.

- The donor. Another way for a non-profit organisation to compose a story designed to encourage people to donate is to show the positive change that people who donate can bring about.

Non-profits tell their stories to the people out there in order to raise awareness, i.e. for them to learn. The effects of this new awareness should be so strong that the audience feels compelled to do something, for example to donate. Show or at least clearly imply the change that an action by the audience, such as making a donation, will bring about.

The process of character development is akin to how some marketers might formulate personas for their target groups. There are a few tools out there to help you, such as www.beemgee.com. While the wording is designed for authors and novelists, the principles can be easily applied to stories told by charities for fundraising.

For an NGO or non-profit that relies on donations from the public, storytelling is part of the communications strategy. Indeed, the way the entire organisation is perceived by the public is as a narrative.

If you’re a fundraiser conceiving a thirty second ad or a blog post, an entire campaign or a simple project description, bear in mind the storytelling pattern we’ve outlined above. Show your audience the difference they can make by supporting your cause.