Mastering Non-Linear Narratives in Modern Storytelling.

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.

In an era where storytelling transcends traditional boundaries, non-linear narratives have emerged as a potent device in the hands of a skillful storyteller. At once complex and captivating, these narratives challenge the time-honored sequence of beginning, middle, and end, engaging audiences with their intricate tapestries of time, memory, and perspective. From the labyrinthine plots of modern novels to the time-bending twists in contemporary cinema, mastering non-linear narratives demands a particular set of storytelling skills. In this article, we delve into the mechanics and artistry that enable modern storytellers to navigate the twists of time adeptly.

Defining Non-Linear Narratives

Non-linear storytelling is characterized by a plot that doesn’t follow a direct causality pattern, a chronological sequence of events, or both. It often involves flashbacks, flash-forwards, and other temporal leaps that demand a higher level of engagement from the audience as they piece the story together.

The Mechanics of Time Manipulation

Mastering the non-linear form requires a deep understanding of the story’s timeline. A storyteller must know the chronological sequence of events, even if the audience will never see the story this way.

Crafting the Jigsaw

In building a non-linear story, think of the narrative as a jigsaw puzzle. Each scene is a piece that, when connected to the broader picture, contributes to the overall story. The order in which these pieces are revealed is crucial in developing suspense, mystery, and dramatic irony. (more…)

Some theorists have posited that stories are all about problem-solving. And certainly – as we have seen – problems are at the very core of story. So by giving the audience a chance to vicariously experience protagonists dealing with problems, a story is in effect a sort of playground or simulation where we can experience what potential problems and solutions feel like – but without any real-life consequences.

An important consideration here is cause and effect. In real life, what we experience has so many causes that it is well-nigh impossible to accurately pinpoint them all. We constantly feel the effects, but it’s hard to pinpoint all the causes. Nonetheless, we really like to have explanations for what’s going on, it gives us a greater sense of control over our own lives. As a species, we seek agency, we’re always looking for what caused something to happen, for the why behind things being as they are. We find it very confusing when we don’t know the reason for the events we live through, and we build elaborate mental constructs to explain to ourselves the world as we perceive it. In this context, we sometimes speak of “narratives”.

In stories, every scene must be the result of a preceding plot event. As we have said before, in between each plot event of a narrative you should be able to place the words not “and then”, but “because of that …”. (more…)

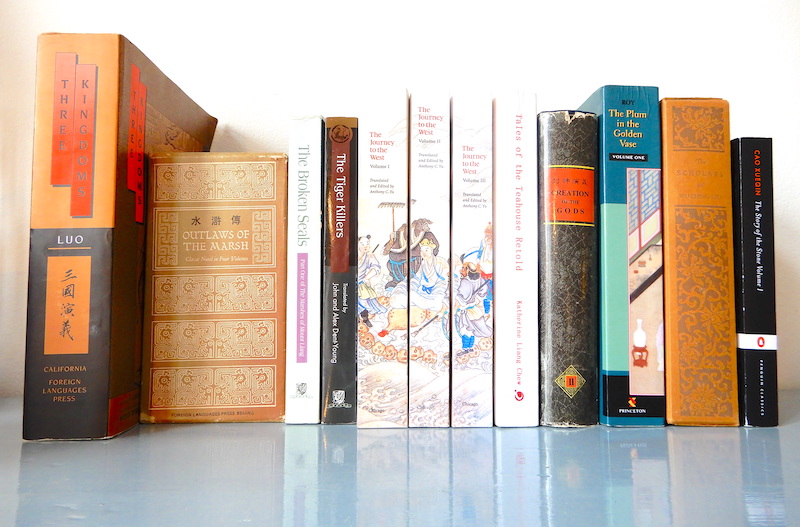

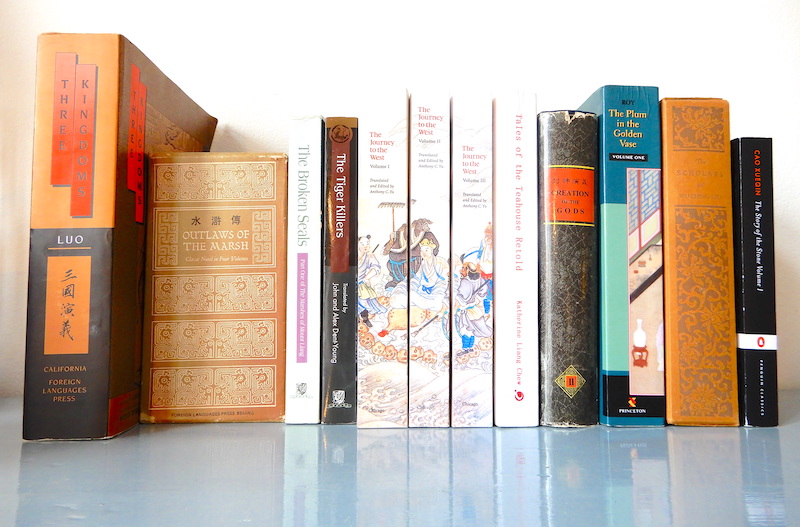

Take a look at your book shelf. Chances are there are European and North American authors there. Perhaps you have some Central or South American writers too. And maybe some Indian or Pakistani novels. And perhaps some Russians.

All of these authors wrote or write in the tradition of European storytelling, via colonial or cultural influence. Modern African authors writing novels, for example, have adopted this written prose text form although African storytelling traditions are primarily oral.

What most of us, at least in the western world, know about how to tell stories is influenced heavily by Aristotle’s Poetics. In this rather thin book, Aristotle describes some basic precepts of dramatic composition that continue to be circulated in creative writing classes and how-to books today.

Another strong influence on western storytelling is the protagonist/antagonist duality which arose along with Christianity. Would there be a Sauron without Satan? A Darth without the Devil? A Voldemort without Lucifer?

So what about stories that were created without any knowledge of Aristotle or Christianity? How are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different?

Let’s find out by asking … (more…)

There are two definitions of story beat. Both of them refer to a change.

One use of the term beat refers to the subtle change in the dynamic of a relationship that a line of dialogue brings about in a scene. There are usually several beats within a scene, each a marker for pushing the scene forwards dramatically.

The other meaning of the word beat in storytelling applies to changes in the plot brought about by scenes. A plot is a succession of events linked causally, a narrative chain of cause and effect. One event effects a change, determining what happens in subsequent scenes. Writers might arrange these events on a board or “beat sheet” during the planning phase. (more…)

Why The Hero Is Never Alone.

Allies Embody the Principle of Cooperation

Despite their complexity and diversity, there are essentially only three different kinds of human relationships.

That’s right, if you take a step back and try to categorize human interactions, you’ll find three distinct types. Biologists know this, because the principle applies to any species that lives in groups. Within the group, three types of behavior may be observed:

- individuals cooperate with each other

- individuals compete with each other

- individuals mate

Evolutionary biologists describe a spectrum of individual to group selection. Some animals will typically try to maximize their individual gain, as exhibited in behaviors such as taking the biggest share of food or the best space for offspring, without regard for other animals in the group. On the other hand, some species have evolved social organizations in which individuals may act purely for the group’s benefit rather than individual gain. Think of ants, bees, or termites.

Interestingly, on this spectrum between profit maximization and altruism, homo sapiens sit pretty much exactly in the middle. Humans are genetically programmed to selfishness, to seek what is perceived as best for oneself and one’s immediate family, and at the same time have a strong and innate instinctive and natural urge towards cooperation and social behavior – which ultimately also increases our survival chances.

Cooperation, neighborliness, charitable behavior, acts of kindness – even if they costs us, they generally make us feel better and they make life in the tribe, clan, or community so much easier. Mind you, we do like to look after number one. We’re not going to simply give up our salaries, our homes, our lifestyles. Our own needs and those of our families come first. Who is not aware of this dichotomy?

The pull in opposite directions between egoism and altruism is perhaps one of the specifics of human beings as a species that has caused us to evolve abstract thought processes as well as complex societal and cultural forms. It also sheds light on basic principles of storytelling such as conflict. (more…)

Where a character comes from may determine their values.

It is not always necessary to explain where a character comes from. Knowing their origin may not help the audience to understand a character.

But for some stories, origins can be vital.

As an example, take a contrast story like In The Heat Of The Night. Police Chief Bill Gillespie lives in the USA’s deep south and is a racist bigot. Such are his values, and for the purpose of this story also his internal problem. That he is a racist does not surprise the audience at all. It is completely credible given his origins. He comes from an area where, at the time at least, such bigotry was rife, and when the African American detective Virgil Tibbs turns up, their conflict is utterly plausible.

What we’re getting at here is that the values of a character have to be made plausible to the audience, which may be achieved by making the origins of that character explicit. In many stories, where a character comes from has to be fitting to what that character is like. Their origin produces the character’s values.

Setting, Origin, and Story World

Are we talking about setting? Well, only to an extent. (more…)

By Lucia Tang.

Lucia is a writer with Reedsy, a marketplace that connects authors with editors, designers, and marketers. In Lucia’s spare time, she enjoys drinking coffee and planning her historical fantasy novel.

Whether we’re piecing together the timeline for a homicide or puzzling out the intricacies of Newtonian mechanics, cause and effect are crucial to how we make sense of, well, everything. Of course, I say “we” loosely. As writers, most of us won’t actually be catching killers or solving the coefficient of fiction. But still, stories are no exception to this rule: without cause and effect, they fall apart.

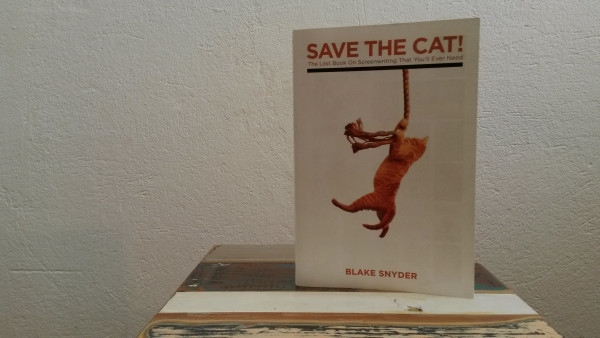

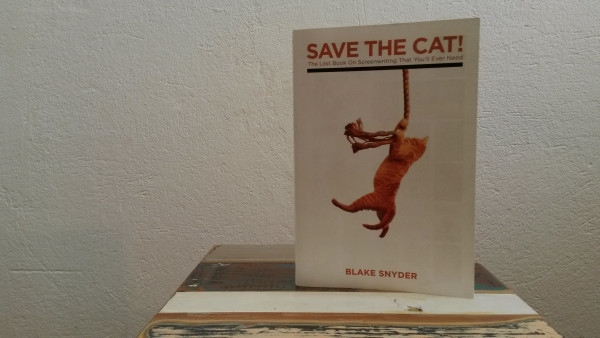

At the end of the day, writers should have as tight a grasp on causality as any detective or physicist. It doesn’t matter if you’re working on a doorstopper to rival War and Peace, or a breezy picture book for baby bookworms: you’ll need to craft a storyline that makes sense. This makes your readers want to spend time in the world you’ve created — and ensures they’ll leave it feeling enlightened and satisfied.

Of course, you can get there haphazardly, writing juicy scenes as they come to mind and attacking the chaos of your draft with a merciless red pen. But if you want to save time during the editing process, keep cause and effect in mind as you plot. (more…)

What do we mean when we talk about story structure?

A story is a complex entity comprising many interrelating parts. The author imposes some sort of organising principle onto the material, turning the story into a narrative. The result of this forming or shaping of the material is the story structure.

Certain structural markers are so explicit that the audience is aware of them, such as chapters in novels. Elizabethan plays are typically divided into five acts. A film script is broken down into acts, sequences, and scenes.

The beat is the smallest unit of story, below the scene in the structural hierarchy. It is the space between an action and the reaction it causes within a scene.

- Beat

- Scene

- Sequence

- Act

- Story

A plot event is not part of this traditional hierarchy, being more of a meta-unit somewhere between beat and scene.

Scenes and acts are defined in screenplays, like chapters in novels. But stories have structures that are not usually made obvious or explicit.

Beats

There are two different understandings of the term beat.

A scene may be broken down into beats – marked only by the moments when the mood or relationship the scene describes changes. Two characters are having a conversation, character A says something which makes character B react in a different way from what A expected – that’s a beat.

The term beat is also sometimes used when marking such changes on a bigger scale, across an entire narrative. Some screenwriters work with so-called beat sheets; in the Beemgee outlining tool, the plot event cards are perfect for creating beat sheets, since each card is designed to stand for one plot event. In a beat sheet, a beat is one unit of plot. If you think of narrative as a chain of events, then each beat is a single link. In one school of thought, a Hollywood movie is ideally constructed of exactly 40 such beats. (more…)

The process of writing is unique to each author.

There is no right or wrong way to write a work of fiction. Perhaps the main thing is to just sit down and get on with it.

Many authors start by writing the beginning of the story and working their way through to the end. This seems intuitive, as it mirrors the way narratives are normally received – from opening to resolution. Furthermore, it allows a development of the material that feels natural, beginning probably with a setting and a character or two and growing in complexity as the story progresses.

But this isn’t the only way to get a story written. The author is not the recipient, after all. The author is the creator.

Creative habits seem to differ according to medium. Most screenwriters spend a lot of time working out the intricacies of plot and complexities of character before beginning to actually write the screenplay. Some novelists, on the other hand, seem to require the writing process in order to get to grips with the material. For such authors, the act of working on text is so intimately intertwined with the craft of dramaturgy that the shaping of the story has to be performed simultaneously with the writing of it.

Flow

In some cases, a writer might have a fairly clear idea in mind where the story is headed, or already be aware of certain key scenes that ought to be included. In others, the author may not know how the story ends(more…)

The step outline is the scene by scene (step by step) account of what happens in the story.

Like a textual storyboard, the step outline presents the narrative in its entirety – without actually being the narrative. It is a complete report of the story – in the present tense! – that describes every plot event.

Cause and Effect

The step outline therefore makes one of the most important principles of storytelling very clear, cause and effect.

Apart from the kick-off event and the closing event, every plot event fulfils two functions, at least to an extent:

- It is a precondition of events that follow it in the narrative

- It is an inevitable consequence of events that have preceded it in the narrative

The step outline should make it easier to understand how the individual events relate to each other in this chain of cause and effect. The step outline may thus be read as the author’s construction plan of the narrative.(more…)

Detectives and other investigators abound on our TV and cinema screens.

In the western world, crime fiction – mystery, thrillers, suspense, whodunnits, etc. – makes up somewhere between 25 and 40 percent of all fiction book sales. Why is the crime genre so popular?

Crime is fascinating, to be sure, because most of us don’t commit it. But the popularity of the genre has little to do with crime per se. It has far more to do with the very essence of how storytelling works.

In this article we will be looking at:

- Cause and Effect

- Agency

- The Whydunnit

- The Narrative Principle

- Why Some People Don’t Like Crime Stories

- The Search For Truth, or Gaining Awareness

- How Crime Is Like Comedy

Cause and Effect

Crime fiction exhibits most clearly one of the fundamental rules of storytelling: cause and effect. In crime fiction,(more…)

Action is character.

So the old storytelling adage. What does that mean, exactly?

In this post, we’ll consider:

- The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

- Actions – what the character does

- Reluctance

- Need

- Character and Archetype

The central or pivotal action – the midpoint

More or less explicitly, the main character of a story is likely to have some sort of task to complete. The task is generally the verb to the noun of the goal – rescue the princess, steal the diamond. The character thinks that by achieving the goal, he or she will get what they want, which is typically a state free of a problem the character is posed at the beginning of the story.

The action is what, specifically, the character does in order to achieve the goal (rescue the princess, steal the diamond). In many cases, this action takes place in a central scene. Central not only in importance, but central in the sense of being in the middle.

Let’s look at some examples. (more…)

In storytelling, a character’s convictions and beliefs determine his or her choice of actions – at least in his or her conscious mind.

Convictions and beliefs are effectively values put into words. They lead to a rationalised intellectual stance and can be the basis for lifechoices and actions. A set of beliefs or convictions is the articulated version of a character’s values or emotional stance.

Consider story’s predisposition for cause and effect. If we understand the belief-system or intellectual stance as the effect, the value-set or emotional stance is the cause. Now, it may be nit-picking to make the distinction between felt values and stated beliefs. But then again, it might be quite helpful to see by what line of reasoning a character justifies his or her behaviour.

The effect can be powerful when there is a discrepancy (i.e. conflict) between what the character thinks is the reason for his or her actions and the real reason. When the audience or readers see that the words and thoughts of a character do not match with what that character is actually motivated by, the irony can be a satisfying story experience.

The Want as Beliefs, the Need as Values

(more…)

A character in a story has values and passions. In short, an emotional stance. It’s this bundle of feelings that make the character a character.

By emotional stance we mean a value-set. This is particularly important when one considers that often stories show value-sets in conflict. The protagonist and in particular the protagonist’s journey to recognition and change may represent certain values. These will be in direct contrast to the antagonist’s values. The theme of the story presents one value-set as preferable over the other.

In many stories, the protagonist starts out with a value-set that is warped or flawed. Their real need is to become aware that their value-set is harmful or negative, probably ultimately selfish, and find a way to gain new values that are more social, cooperative and selfless. For the purpose of such a story, the values are initially expressed in the internal problem and by the end have gone through a change.

Values do not emerge in a vacuum, they are instilled by environment or culture. Stories exhibit cause and effect, and the values of each of the characters are no exception. The audience looks for the causes of a character’s emotional stance. By the very nature of emotions and values, their causes can be hard to pinpoint – while at the same time being somewhat obvious. In stories, at least.

Furthermore, values are emotional and therefore exist before they are articulated. A character becomes conscious of a value-set in the form of a system of beliefs. The beliefs are articulated by the character as convictions, and are determined by inner values. In some cases, the stated beliefs may actually be in conflict with the character’s deeper values, of which the character may not be entirely aware. Values tend to feel right to the individual, though they may actually be wrong for the larger community or society.

A character’s values have to be plausible to the audience, which may be achieved for instance giving the characters appropriate social backgrounds or origins and making these explicit. In many stories, a character’s upbringing or their origin is named or described in order to explain their emotional stance.

Alternatively, values may be caused by certain specific events in the history or background of a character, conveyed as backstory in the narrative. A particular circumstance, possibly a trauma, leads the character to feel a certain way about life and the world.

Character Values in Historical Stories

In historical stories the time-setting is particularly challenging in terms of the emotional stance of the characters. Much popular historical fiction may justly be termed anachronistic in that it has characters – especially female protagonists! – exhibiting values and beliefs which do not fit into the time. For example: In the Middle Ages, the advent of humanism had not occurred yet. There had been no Renaissance, no Descartes, no Kant, no French Revolution and no American Constitution. Where is a character in the Middle Ages supposed to get ideas, values and convictions from that today we take for granted? Ideas about inalienable rights such as liberty and equality or concepts such as individualism. People in the past had different values and belief systems from people today, and it is almost impossible to put ourselves in their shoes. Historical fiction that does not at least implicitly deal with this challenging issue is more likely to be clichéd and trivial.

Which does not mean that trivial historical stories can’t be wildly entertaining with strong emotional impact. After all, modern stories address the audience of today. It means simply that an author usually has some sort of attitude to the issue.

Photo by Wonderlane on Unsplash

Related function in the Beemgee story development tool:

Character Developer

Already using the author tool? If not, try it here:

It’s the way you tell it.

Narrative is the choice of which events to relate and in what order to relate them – so it is a representation or specific manifestation of the story, rather than the story itself. The easy way to remember the difference between story and narrative is to reshuffle the order of events. A new event order means you have a new narrative of the same story.

Narrative turns story into information, or better, into knowledge for the recipient (the audience or reader). Each story event is a unit of knowledge the audience requires.

A narrative is paradox, because it seeks to convey truth by hiding it. A storyteller arranges the items of knowledge in such a way that they are revealed gradually, which implies initially obscuring the truth behind what is told. Such deliberate authorial obfuscation creates a sense of mystery or tension, and creates a desire in the audience to find out what is happening in the story and why. In this sense, a narrative is effectively the opposite of an account or a report.

A report presents information in order to be understood by the audience immediately, as it is being related. A neutral, matter of fact presentation probably maintains a chronology of events. It explains a state of affairs blow by blow, and aims for maximum clarity at every stage. It seeks to convey truth by simply telling it. While the point of a narrative is also that the recipient perceives the truth of the story, in a narrative this truth is conveyed indirectly. Narrative is therefore responsible for how the recipient perceives the story.

In this article we’ll look at

- Story Basics

- The Components of Story

- Text Types That Describe A Story

- Author Choices: Genre and Point of View

- Causality in Narrative

Story Basics

First, let’s state some basics as we understand them here at Beemgee: a story consists of events that are related by a narrator; events consist of actions carried out by characters; characters are motivated, they have reasons for the things they do; there is conflict involved; one and the same story may be told in different ways, that is, have varying narratives.

Note that we are talking here about narrative in the dramaturgical sense – not in the social sense. Like the term “storytelling”, the word “narrative” has become a bit of a buzzword. We are not referring here to open “social narratives” such as “the American narrative”. For the definition and exploration of such collective narratives, see our article in The Bigger ‘Narratives’ of Society. Here, we are pinpointing the use of the term primarily for storytellers creating novels, films, plays, and the like. Such works tend in their archetypal form to be closed narratives with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

A narrative may present the events of the story in linear, that is to say chronological order or not. But the story remains the story – even if it is told backwards.(more…)

Stories are about people. Even the ones about robots, or rabbits, or whatever.

If you’re thinking about composing a story, you will probably have some characters in mind that will be performing the action of the story. In stories, action and actors (in the sense of someone who does something) are pretty much the same thing looked at from two differing perspectives, as we have noted in our post Plot vs. Character.

The most obvious difference between characters in stories and people in real life is that story characters tend to be driven. Narratives tend to be more compelling when the characters they describe are highly motivated. Rarely in life are our wants, goals, and perceived needs as clear and powerful as for characters in stories. Our real lives tend to drift rather than head in a specific direction; it is often in retrospect that we ascribe direction when we try to understand our lives by putting them into narratives. Historical personages who seem to demonstrate drive and direction (and have perhaps become historical personages because they had these qualities) make for more interesting biographies than people whose motivations were less strong.

Another aspect that sets characters in fiction apart from people in life is that characters tend to fulfil narrative functions in their story. People, on the other hand, live their lives by acting naturally according to the dictates of their personality. A story is a more or less enclosed unity, while an individual’s life is part of a greater whole. Only in retrospect do we sometimes overlay a narrative onto the biography of an individual – because we tend to feel happier when we perceive structure or direction in the lives of others or indeed our own. We can extract more meaning out of a life that can be told with structure and direction. In fact, there is no way of recounting a person’s biography without making choices concerning structure. If we’re honest, even the choice of which events to relate and how to relate them injects a fair amount of fiction into the story of a life, especially when that life is our own as we tell it to others or ourselves.

Many stories focus primarily on one protagonist. In fiction at least, the protagonist is often wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. The(more…)

We humans have a built-in predisposition to expect agency.

We look for the person or thing responsible for any action or phenomena we experience; we seek to ascribe “agency” to what we perceive. What this means is that when we notice that something happened, we tend to look for the cause of the event. This probably has a simple evolutionary explanation. If we hear a rustle in the bush behind us, we immediately turn around to see what moved. This reflex is a safety mechanism to detect threats. Before homo sapiens lived in houses, the individuals for whom this reflex worked most efficiently probably lived longer, and thus had better chances of passing on their genes. The point is, we assume that something or someone caused the phenomenon (the rustle) and seek to attribute it to an agent. If we are sitting in our living room and hear a floorboard creak in the hall, we would want to know what caused it too.

This safety mechanism has all sorts of ramifications. It influences(more…)

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.