Mastering Non-Linear Narratives in Modern Storytelling.

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.

In an era where storytelling transcends traditional boundaries, non-linear narratives have emerged as a potent device in the hands of a skillful storyteller. At once complex and captivating, these narratives challenge the time-honored sequence of beginning, middle, and end, engaging audiences with their intricate tapestries of time, memory, and perspective. From the labyrinthine plots of modern novels to the time-bending twists in contemporary cinema, mastering non-linear narratives demands a particular set of storytelling skills. In this article, we delve into the mechanics and artistry that enable modern storytellers to navigate the twists of time adeptly.

Defining Non-Linear Narratives

Non-linear storytelling is characterized by a plot that doesn’t follow a direct causality pattern, a chronological sequence of events, or both. It often involves flashbacks, flash-forwards, and other temporal leaps that demand a higher level of engagement from the audience as they piece the story together.

The Mechanics of Time Manipulation

Mastering the non-linear form requires a deep understanding of the story’s timeline. A storyteller must know the chronological sequence of events, even if the audience will never see the story this way.

Crafting the Jigsaw

In building a non-linear story, think of the narrative as a jigsaw puzzle. Each scene is a piece that, when connected to the broader picture, contributes to the overall story. The order in which these pieces are revealed is crucial in developing suspense, mystery, and dramatic irony. (more…)

The Two Types of Non-Fiction Book.

Here at Beemgee, we know a lot about how stories work. We consider ourselves experts on dramaturgy and narrative. Fiction is our forte.

But we don’t claim to understand non-fiction anywhere near as well. That’s why we were very keen to attend a session on non-fiction by Yvonne Kraus at the author conference at this year’s Leipzig book fair.

Here’s a brief summary of what she taught us.

The Two Basic Structures of Non-Fiction Books

1. Reference and articles

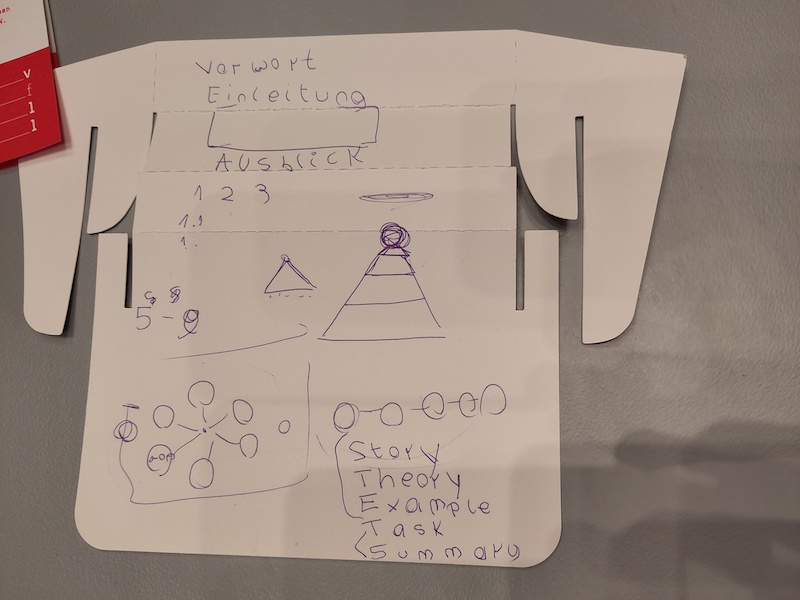

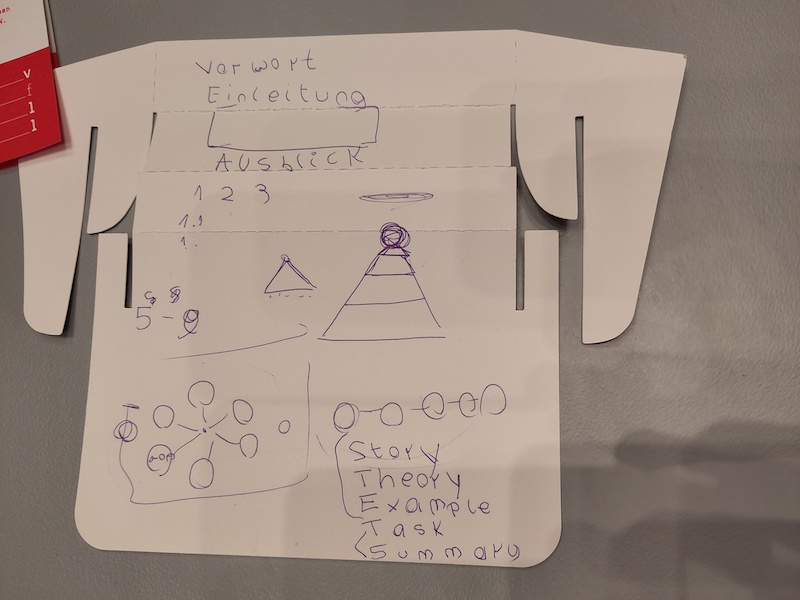

Look at the bottom left of the scribble in the photo and you’ll see circles arranged in a circle, with lines going from the individual circles into the center of the arrangement. Each individual circle stands for a unit of content, or a chapter. This representation is trying to express a way of reading a book. The reader can dip into any chapter at will, they each function independently of each other, it is not necessary to read them in sequence or to read all of them. Cookbooks are a good example. Each recipe constitutes a chapter, a unit, and can be consulted without knowing the other units.

If we are talking about content more complex than recipes, for example political articles, the units may contain information that is repetitious in the book as a whole if this information is necessary in order to understand the content of several individual chapters. I.e. it may well be the case that the same basic facts are stated in several of the chapters if they are requisite to know, because the author cannot assume that the reader will have read previous chapters in the book already. The chapters do not build on each other. Certain units of information may be referenced, for example a lasagne recipe may call for béchamel sauce, the making of which may not be described in the lasagne recipe but instead the lasagne recipe may simply say, “see the recipe for béchamel sauce on page 27 in the section ‘basic sauces'”.

The main body of the book may be subdivided into meaningful sections. The promise the book makes to the reader is that the reader will find specific information on a particular subtopic easily, and without having to read the entire book. (more…)

Outlining a story means developing the characters and structuring the plot.

Beemgee will help you outline your plot using the principle of noting ideas for scenes or plot events on index cards and arranging them in a timeline. This is a separate process from actually writing the story. Most accomplished authors outline their stories before writing them, because it saves rewrites later.

Find a video here.

In this post we will explain –

The Beemge author tool is divided into three separate areas, PLOT, CHARACTER and STEP OUTLINE. You navigate them easily in the top menu.

Important note: Make sure to stay in the same browser window in whichever area you’re working. Having one project open in multiple windows may result in some of your input being lost.

How To Create An Event Card

(more…)

Five years ago, three guys met at a notary’s office in a rather run-down part of Berlin.

They had decided to found a company, and on this day were making the declaration official – although they had no backing and no product. Why?

The circumstances of each of the three guys were quite different. One was employed, the other already ran his own business, the third had just left his job. Two were techies, one was the content guy, the one with the idea.

Looking back on it, what they had in common was the desire for a sense of purpose. Each of them wanted their working life to follow a vision, rather than a loop.

For let’s face it, most work is repetitive. You end up going through the same motions again and again, whatever they are.

But found your own company and you’re aiming at something. You’re pursuing a vision. You set yourselves goals, milestones. You have an ideal state you wish to achieve. And probably no idea what you’re letting yourself in for.

In short, when you found a company you become the protagonist in your own story. (more…)

It’s the way you tell it.

Narrative is the choice of which events to relate and in what order to relate them – so it is a representation or specific manifestation of the story, rather than the story itself. The easy way to remember the difference between story and narrative is to reshuffle the order of events. A new event order means you have a new narrative of the same story.

Narrative turns story into information, or better, into knowledge for the recipient (the audience or reader). Each story event is a unit of knowledge the audience requires.

A narrative is paradox, because it seeks to convey truth by hiding it. A storyteller arranges the items of knowledge in such a way that they are revealed gradually, which implies initially obscuring the truth behind what is told. Such deliberate authorial obfuscation creates a sense of mystery or tension, and creates a desire in the audience to find out what is happening in the story and why. In this sense, a narrative is effectively the opposite of an account or a report.

A report presents information in order to be understood by the audience immediately, as it is being related. A neutral, matter of fact presentation probably maintains a chronology of events. It explains a state of affairs blow by blow, and aims for maximum clarity at every stage. It seeks to convey truth by simply telling it. While the point of a narrative is also that the recipient perceives the truth of the story, in a narrative this truth is conveyed indirectly. Narrative is therefore responsible for how the recipient perceives the story.

In this article we’ll look at

- Story Basics

- The Components of Story

- Text Types That Describe A Story

- Author Choices: Genre and Point of View

- Causality in Narrative

Story Basics

First, let’s state some basics as we understand them here at Beemgee: a story consists of events that are related by a narrator; events consist of actions carried out by characters; characters are motivated, they have reasons for the things they do; there is conflict involved; one and the same story may be told in different ways, that is, have varying narratives.

Note that we are talking here about narrative in the dramaturgical sense – not in the social sense. Like the term “storytelling”, the word “narrative” has become a bit of a buzzword. We are not referring here to open “social narratives” such as “the American narrative”. For the definition and exploration of such collective narratives, see our article in The Bigger ‘Narratives’ of Society. Here, we are pinpointing the use of the term primarily for storytellers creating novels, films, plays, and the like. Such works tend in their archetypal form to be closed narratives with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

A narrative may present the events of the story in linear, that is to say chronological order or not. But the story remains the story – even if it is told backwards.(more…)

Narrative is made of successive events. Not necessarily in the order they occurred.

Narrative is the order in which the author presents a story’s events to the recipient, i.e. the audience or reader. Chronology is the order of these events consecutively in time. Some people use terms from Russian Formalism, Syuzhet and Fabula, to make the distinction.

A chronology usually has less emotional impact than a narrative – essentially a chronology is recounting a report whereas a narrative is telling a story. In a chronology, the plot events are lined up in temporal sequence. You could say “and then” between each event. In a narrative, the emotional effect is closely related to the causality implied by the arrangement of the events. Between each event you could say, “because of that …”.

Narrative therefore carries with it the implication of understanding. The juxtaposition of events, for example, will create associations in the audience’ minds that lead to possibilities of interpretation. While a chronology may explain things, it is in itself inherently neutral. Narrative on the other hand is an arrangement that is usually consciously made by an author who intends something by the particular arrangement, and which, independently of author intention, is subject to interpretation by recipients.

While the convention in most storytelling is linear, i.e. to relate the story’s events consecutively in time (chronologically), we as audiences and storytellers are also very used to narratives that move certain events around. An event may be moved forward, meaning towards the beginning of the narrative, perhaps even to be used as a kick-off. Or possibly events may be withheld from the audience or reader and pushed towards the end, perhaps to create a reveal late in the narrative for a surprise effect – though this technique often feels cheap. Also, an author may use flashbacks to insert backstory events from the past, the past being all relevant events that take place before scene one in the narrative.

As authors, when we begin composing a story, we(more…)

Inventing a story that has no backstory is about as easy as finding a perfect rhyme for the word orange.

That is, next to impossible.

Backstory is the stuff that went on before the story begins, or more precisely, before the kick-off event in scene 1. As such, backstory might better be called “pre-story”. It is a necessary component of any story.

After all, the characters come from somewhere – they have pasts, they have histories. These histories have shaped them into who they are, which determines their actions now, in the time of the story. These actions are the source of the events of the story. So some part of the characters’ histories will be relevant to the story – and this bit of information or knowledge needs to be passed on to the audience or reader. That’s why so many stories have “campfire scenes”, a moment of calm usually near the beginning of the second half during which characters recount stories of their pasts to each other. (more…)

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.