The stories we tell each other collectively – sorting out the meanings of the word “narrative”, we find the fiction behind the fact.

Some words are so big that they become meaningless.

Let’s put that more precisely: Some terms are used so generally that their denotations are harder to pinpoint than people who use or people who hear such words may realize. Try to define exactly what “freedom” means, or “democracy”.

Out of the field that concerns us here, at least two terms have reached this general ‘buzzword’ status: “storytelling” and “narrative”.

There are professions and there are fields of study trying to get to grips with storytelling and narrative, for instance the profession of dramaturg or the theoretical approaches of narratology.

- Dramaturgy is defined as the craft, art, or the practice and techniques of dramatic composition or theatrical representation, where composition refers to the way in which the various parts are put together and arranged. In other words, structure.

- Narratology is defined as the study of structure in narratives or the study of narrative and narrative structure, where a narrative is something that is narrated, a representation or description of an event or series of events with the connections between them – that is, of a story.

Especially in American English, there is a second meaning to the word narrative, one that hasn’t made it into the British Collins dictionary yet and only to 2c in the OED, though by now the term is used widely in UK media in the same way as in the States and the rest of the world: “A way of presenting or understanding a situation or series of events that reflects and promotes a particular point of view or set of values“ (Merriam-Webster). In other words, ideology.

In this second definition, the term “point of view” is used generally, not in the technical or dramaturgical sense that a cameraperson or a novelist would use when talking about a scene. In the same way that PoV is a far narrower technical term within storytelling than in general use, so is “narrative” far broader in general use than among authors talking shop. Hence for technical use, we need yet another definition, one that is much more precise than what you find in a general dictionary: (more…)

Dramaturgical techniques in news stories.

This post is adapted from a longer piece by one of our founders on his personal Substack. Read the full article here (just click “no thanks” if you don’t want to subscribe).

If we’re watching a movie or reading a novel, we want a good story that reaches us on an emotional level. We demand to be excited, moved, aroused, even outraged or scared witless.

People enjoy the emotions that stories provoke. Emotional responses are the reason we succumb to stories, and storytellers deliberately try to elicit the “visceral” effect that powerful feelings engender. In order to root for the heroine, she must be placed in danger; in order to empathise with the hero, the audience must be able to identify with him and care about his fate. Writers and storytellers do a lot to engage the audience and keep them reading or viewing. The best techniques to maintain the audience’ attention are the ones that grab the audience emotionally. Stir them! Excite them! Make them feel! Boredom sets in when there is no increased heart rate, no sweaty palms, no rapt attention.

“Our top story tonight: …”

Newspapers and other news media such as television or online news portals know as well as novelists and moviemakers that the promise of emotion is what gets the audience’ attention in the first place and the delivery of emotion is what maintains it. Hence news media employ some similar techniques to fiction authors and screenwriters. Not for nothing is a news show or paper divided into “stories”. (more…)

The Two Types of Non-Fiction Book.

Here at Beemgee, we know a lot about how stories work. We consider ourselves experts on dramaturgy and narrative. Fiction is our forte.

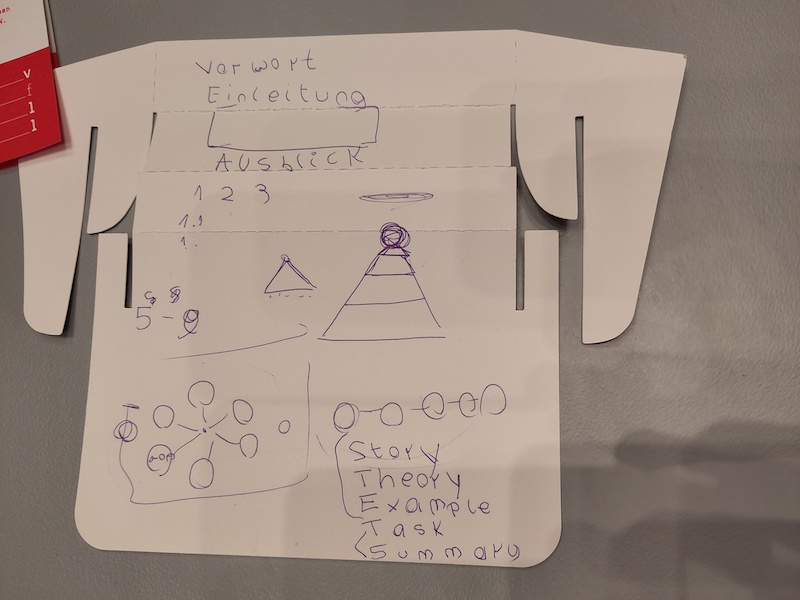

But we don’t claim to understand non-fiction anywhere near as well. That’s why we were very keen to attend a session on non-fiction by Yvonne Kraus at the author conference at this year’s Leipzig book fair.

Here’s a brief summary of what she taught us.

The Two Basic Structures of Non-Fiction Books

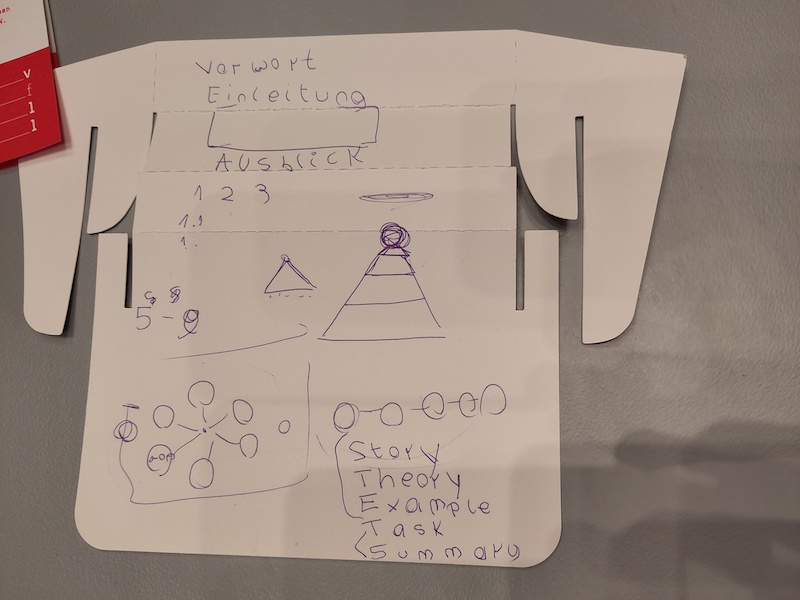

1. Reference and articles

Look at the bottom left of the scribble in the photo and you’ll see circles arranged in a circle, with lines going from the individual circles into the center of the arrangement. Each individual circle stands for a unit of content, or a chapter. This representation is trying to express a way of reading a book. The reader can dip into any chapter at will, they each function independently of each other, it is not necessary to read them in sequence or to read all of them. Cookbooks are a good example. Each recipe constitutes a chapter, a unit, and can be consulted without knowing the other units.

If we are talking about content more complex than recipes, for example political articles, the units may contain information that is repetitious in the book as a whole if this information is necessary in order to understand the content of several individual chapters. I.e. it may well be the case that the same basic facts are stated in several of the chapters if they are requisite to know, because the author cannot assume that the reader will have read previous chapters in the book already. The chapters do not build on each other. Certain units of information may be referenced, for example a lasagne recipe may call for béchamel sauce, the making of which may not be described in the lasagne recipe but instead the lasagne recipe may simply say, “see the recipe for béchamel sauce on page 27 in the section ‘basic sauces'”.

The main body of the book may be subdivided into meaningful sections. The promise the book makes to the reader is that the reader will find specific information on a particular subtopic easily, and without having to read the entire book. (more…)

These are remnants of our sessions at the wonderful Author Conference at the Leipzig Book Fair, LBM24. As you can see, we really can’t draw. Nonetheless we tried to illustrate sophisticated approaches to storytelling such as:

– figural shadowing

– liminal storytelling

– cyclical and rhythmic storytelling

We hope our participants gained some valuable insights!

Click to develop a better story:

Guest post by Ali Luke.

Ali Luke is a freelance writer and novelist who blogs about making the most of your writing time at Aliventures. For her best tips on making time to write, sign up for her email newsletter: you’ll receive a free copy of her mini ebook Time to Write: How to Fit More Writing Into Your Busy Life, Right Now.

Ali Luke is a freelance writer and novelist who blogs about making the most of your writing time at Aliventures. For her best tips on making time to write, sign up for her email newsletter: you’ll receive a free copy of her mini ebook Time to Write: How to Fit More Writing Into Your Busy Life, Right Now.

Pacing in fiction is how quickly—or slowly—the story progresses. The right pace for a story depends on its genre. If you’re reading a thriller, you’ll expect a fast-paced read with lots of action; if you’re reading a historical novel or epic fantasy, you might enjoy a slower pace with lots of emphasis on the world of the story.

It’s tough to get pacing spot-on when you’re drafting. It might take you years to write a book that takes just hours for someone to read. What feels “slow” to you as you write might actually go by pretty quickly on the page. Or, you may find that you repeat yourself, going over the same narrative ground multiple times, because you barely remembered what you wrote six months ago.

So, don’t worry about your pacing as you draft. Instead, address it in the redrafts—ideally, with the help of beta readers, but even simply reading over your full manuscript yourself can help you spot areas where the pace feels off.

Here’s what to look for when redrafting your work. (more…)

Some Points to Ponder.

Should we reassess the success of our storytelling?

The Evolution of Stories

In previous posts we described the evolutionary case for storytelling. There is a point to telling stories, a reason why we do it. Stories have a deep “biological” function. The idea is that the fact that we as a species tell each other stories is an evolutionary adaptation which has increased our ability to survive and thrive on this planet.

And while the argument seems very plausible to us, the description of humans as “the storytelling animal” also seems to us to indicate the typical hubris of our species. By calling ourselves that, we set ourselves apart from the other animals who share our planet, who ostensibly are not intelligent or gifted enough to be endowed with an instinct for narrative.

But who is to say that whales, wolves, or even bees don’t tell each other stories?

If an elephant never forgets, surely their memories are filled with events and occurrences? And who is to say there are no plots and characters in these reminiscences, no themes or motifs in those recollections, no dramaturgy to those pachiderm pasts? (more…)

How perceptive a character is of her surroundings may have dramaturgical relevance.

A character who is good at noticing small details may make a good spy or detective, so if you are developing a detective or spy you may want to give your character this ability. But whatever your character’s profession, stop at least once per scene and ask yourself,

What is a detail that only this character might notice?

Why is this important? Because their perceptions can make characters more interesting and vivid.

If a certain plot event hinges on a character perceiving some small detail or other, it may be a good idea to plant a foreshadowing moment long before the scene, to heighten the impact of the act of perception.

Furthermore, a character’s perception may influence how your audience understands and enjoys the entire story. How exactly depends on two important factors:

- narrator

- point of view

(more…)

Long or short form, commercial or artistic: stories need to be developed before they are told.

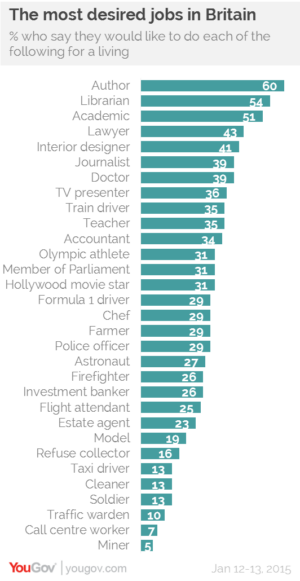

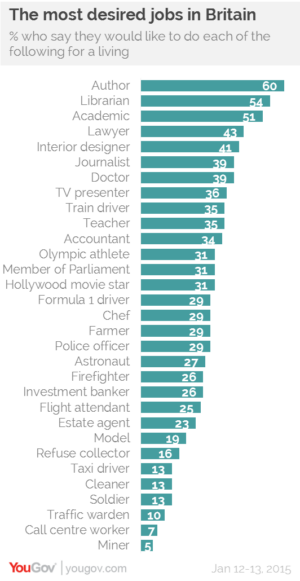

The fewest of people with the inclination to write stories actually make a living off it. There are more unsuccessful authors and screenwriters than successful ones, if we measure success in terms of monetary remuneration. And there are yet more people who would love to write that book but never seem to get around to it.

In fact, according to a 2015 YouGov poll in the UK, being an author is the most desirable job in that country. 60% of Britons want to write for a living! In the land of the Bard, J.K. Rowling, and Richard & Judy, perhaps that is not so surprising. Yet we may assume that in other countries too, the desire to tell stories is quite prevalent.

Practice makes perfect, so they say. The best way for a writer to improve their writing is to write. You may have heard of the theory that to be really, really good at something, you need to have done 10,000 hours of it.

But who has 10,000 hours to spare before producing anything readable?

We would contend that any writing is practice. The artist in the garret must eat and so a suitable option would be earning from writing. This is, after all, an age in which content is regent. Perhaps it is even true that more stories are being told today than ever before. There is an abundance of media and channels, and all must be filled with material. Hundreds of original series are being produced for the streaming services, cinema is not dead after all, and neither is TV, publishers are still publishing novels while self-publishers do it too.

Advertising is another field in which storytellers can hone their craft. Every company needs its image video, every product its presentation. Even towns, nonprofits, and unions tell stories. (more…)

A story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. How to avoid the ‘saggy middle’.

The middle bit of a story is really the story proper. It is usually the longest section. It comes after the introduction of the main character(s) and the setting up of the context, that is the world of the story, as well as the problems and themes the story deals with.

At the end of the first section – prior to what we’re here calling ‘the middle bit’ –, the protagonist has decided to set off on the story journey. Obviously, this does not have to be physical journey through a particular geography, but it does mean that the main character is somehow entering into new and unfamiliar terrain. In this sense, every story is a ‘fish out of water’ story. The heroine must leave the comfort zone in order for the audience to feel interest in her plight.

Some authors jump right into this unfamiliar territory, showing the run up to it in flashbacks. Anita Brookner’s heroine Edith Hope has already arrived in the Hotel du Lac in the first sentence of the novel. Gradually the reasons for her stay here are revealed as the reader progresses through the novel.

Nonetheless, for an author, it may be advisable to create a marked threshold where the protagonist enters into the alien territory of the middle bit. The exploration and transversal of this territory is what on a plot level the middle bit is about, and it takes up the greater part of the story journey. (more…)

Creation Takes Time.

This is an age of faster, faster, more, more. At the latest since the advent of the internet, everything seems to be speeding up. Processes that took weeks a few decades ago now take only a few hours, things that in the twentieth century took hours now take place within minutes or seconds. You can get from A to B in less time than ever. The requirements on most of us for most of our work call for ever greater efficiency. We must not waste time. We must be quick.

Composing a story is a painstaking process. And yes, here at Beemgee we built our fiction tool in order to make the process of composing a story more efficient. We want to make it easier to organise a plot and determine the characters’ motivations – for the authors themselves, and for all the people communicating about the story, so between interested parties such as authors and their editors or screenwriters and producers.

But though we might want our authors’ efficiency to increase, let’s not kid ourselves. Composing a story is still a painstaking process. Because most of the time is spent thinking.

Thinking takes time. And that is mostly what plotting and outlining a story really is, thinking. (more…)

What a character might know that others don’t – including the audience

Some characters have secrets. We are not necessarily talking about their internal problem or the need that arises out of it (they may be aware of such a problem or not.) We are talking about information that makes a difference to the story once it is shared.

Character secrets are intimately bound to the scene type called a reveal (which does not necessarily have to entail a revelation).

In terms of story (or rather the dramaturgy of the story), if a character has a secret that is never revealed, the secret is irrelevant. Only if the secret is made known at some point in the narrative does it really exist as a component of the plot.

For authors, the main aspects of character secrets to control are:

- What plot event brings the secret about (this may be a backstory event)?

- How does the secret alter or determine the character’s decisions or behaviour?

- Does the character share the secret with another character at any point, and if so when (in which scene)?

- At what point in the narrative (in which scene) does the audience receive knowledge of this secret?

Who are you, really?

If it is so important the character has a secret, then, often, the secret becomes part of who this character is. Their role in the story, their identity within the story, is determined by their secret. So secrets are dramaturgically important. (more…)

The midpoint is structurally the most significant point in a narrative.

Given that stories have a tendency to symmetry, the centre of a narrative should mark the zenith of the story arc, and with that, the pivotal point of the story.

So, to get to (mid)point: What happens in the middle of a story?

Here are some typical midpoint events:

- Something searched for is found (Star Wars IV, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lolita)

- A hidden truth is unveiled (to the audience, at least) – if not yet understood (Matrix, Pride and Prejudice, The Gruffalo)

- A dramatic event thwarts all plans made hitherto (James Cameron’s Titanic)

The centre of the narrative may be the discovery of something missing – in crime stories a vital piece of the puzzle may be revealed here (either to the audience or to the audience as well as the protagonist).

In any genre or dramatic category, the midpoint may be a moment of truth. This might be just a clue for the audience or perhaps an initial revelation of the true state of things.

If a character realises or finds out something that has so far been hidden, then this is the point at which the character begins to gain awareness. This counts in particular for the recognition of the character’s own internal problem. From here on the story might possibly lead up to a moment of choice at the crisis, when it becomes clear to the audience whether the character has learnt from this new awareness or not. In other words, the real need begins to overcome or supplant the character’s initial want due to what happens at the midpoint.

Some well-known examples of the midpoint

(more…)

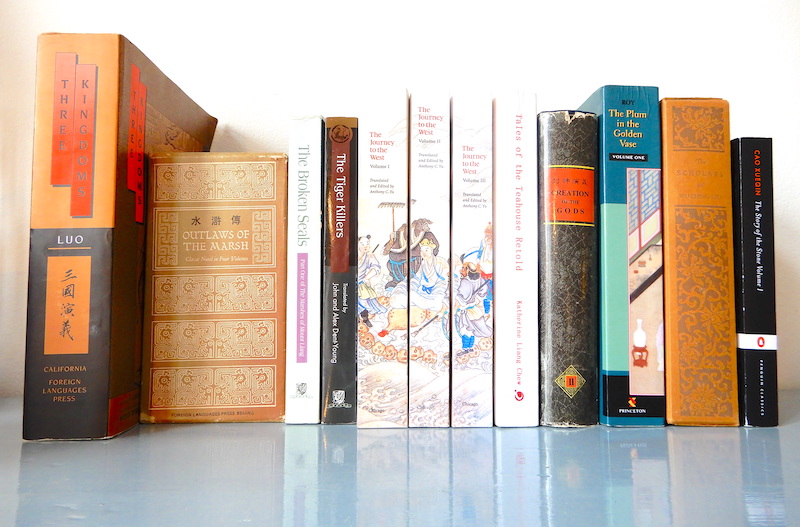

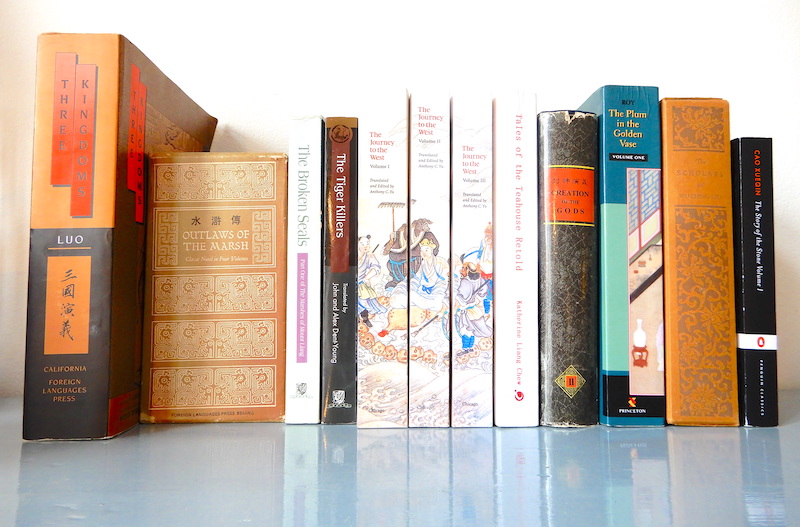

Take a look at your book shelf. Chances are there are European and North American authors there. Perhaps you have some Central or South American writers too. And maybe some Indian or Pakistani novels. And perhaps some Russians.

All of these authors wrote or write in the tradition of European storytelling, via colonial or cultural influence. Modern African authors writing novels, for example, have adopted this written prose text form although African storytelling traditions are primarily oral.

What most of us, at least in the western world, know about how to tell stories is influenced heavily by Aristotle’s Poetics. In this rather thin book, Aristotle describes some basic precepts of dramatic composition that continue to be circulated in creative writing classes and how-to books today.

Another strong influence on western storytelling is the protagonist/antagonist duality which arose along with Christianity. Would there be a Sauron without Satan? A Darth without the Devil? A Voldemort without Lucifer?

So what about stories that were created without any knowledge of Aristotle or Christianity? How are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different?

Let’s find out by asking … (more…)

Nothing should be more important to an author than how their story makes the audience feel.

As an author, consider carefully the emotional journey of the reader or viewer as they progress through your narrative.

The audience experiences a sequence of emotions when engaged in a narrative. So narrative structure is a vital aspect of storytelling. The story should be touching the audience emotionally during every scene. Furthermore, each new scene should evoke a new feeling in order to remain fresh and surprising.

The author’s job is to make the audience feel empathy with the characters quickly, so that an emotional response to the characters’ situation is possible. Only this can lead to physical reactions like accelerated heartbeat when the story gets exciting. We have to care.

This “capturing” of the audience, making the reader or viewer rapt and enthralled, requires authors to create events that will show who the characters are and how they react to the problems they must face. The audience is more likely to feel with the characters as the plot unfolds when the characters’ reactions to events reveal something about who they really are – and how they might be similar to us.

One Journey to Spellbind Them All

Here we present a loose pattern that we think probably fits for any type of story, whatever genre or medium, however “literary” or “commercial”. It’s not prescriptive, just a rough checklist of the stages in the emotional journey the audience tacitly expects when they let themselves in on a story. The emotions are in more or less the order they might be evoked by any narrative.

Curiosity

(more…)

Outlining a story means developing the characters and structuring the plot.

Beemgee will help you outline your plot using the principle of noting ideas for scenes or plot events on index cards and arranging them in a timeline. This is a separate process from actually writing the story. Most accomplished authors outline their stories before writing them, because it saves rewrites later.

Find a video here.

In this post we will explain –

The Beemge author tool is divided into three separate areas, PLOT, CHARACTER and STEP OUTLINE. You navigate them easily in the top menu.

Important note: Make sure to stay in the same browser window in whichever area you’re working. Having one project open in multiple windows may result in some of your input being lost.

How To Create An Event Card

(more…)

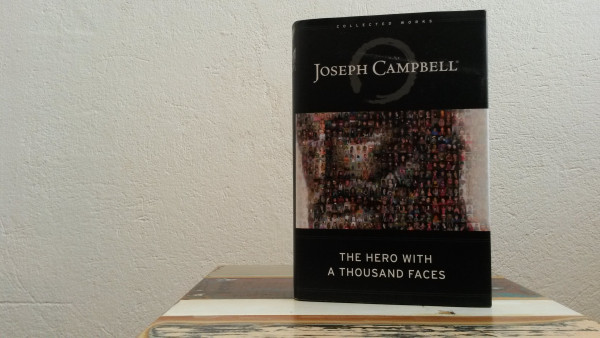

Joseph Campbell: The Hero With A Thousand Faces.

Joseph Campbell’s study of worldwide myths, The Hero With A Thousand Faces (1949), has become massively influential in commercial storytelling. Campbell was not the first to consider the concept of the hero and mythological or archetypal stories, and by no means the last (see Northrop Frye, as well as Robert Scholes and Robert Kellogg). But Campbell’s work consolidated what others, including Carl Jung, had suggested into a theory specifically about storytelling.

George Lucas read The Hero With A Thousand Faces as a young man, and we may assume that Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg were also familiar with the book. We can see the influence of Campbell’s ideas on some of the most successful movies of the 1970s and 80s, and ever since.

Christopher Vogler studied film at the same school as George Lucas, and subsequently while working at Disney wrote a seven-page breakdown of Campbell’s book. This in time developed into The Writer’s Journey, which has become the basis of the popular conception of The Hero’s Journey.

Campbell was an expert on James Joyce and a professor of literature with a particular interest in comparative mythology and comparative religion. The Hero With A Thousand Faces is by no means a how-to book or a storytelling manual. Rather, it posits the theory that all the myths of the world have elements in common and propounds the idea of the “monomyth” as a basic structural model of traditional storytelling. (more…)

Is there a recipe for successful stories?

In search of a recipe for success, Hollywood development executive Christopher Vogler wrote a seven-page practical guide for Disney to Joseph Campbell’s comparative analysis of worldwide myths.

George Lucas had already stated his debt to Campbell in the development of Star Wars, and the idea that there might be a template for stories that are so successful they last over centuries and across cultures caught on quickly in Tinseltown. (more…)

There are two definitions of story beat. Both of them refer to a change.

One use of the term beat refers to the subtle change in the dynamic of a relationship that a line of dialogue brings about in a scene. There are usually several beats within a scene, each a marker for pushing the scene forwards dramatically.

The other meaning of the word beat in storytelling applies to changes in the plot brought about by scenes. A plot is a succession of events linked causally, a narrative chain of cause and effect. One event effects a change, determining what happens in subsequent scenes. Writers might arrange these events on a board or “beat sheet” during the planning phase. (more…)

Set the structure markers in the NARRATIVE order, see them in both sort orders.

(more…)

What does meaning mean? When is a tale meaningful? A few perspectives on imbuing your plot and characters with a subtext.

It’s no mean feat to make your audience feel they have learned something through your story.

Meaning is that which is intended or understood. The audience draws significance, relevance or profundity out of a story when it understands the deeper implications, reasonings and causes behind it. The meaning of a story depends on the standpoint. An author may mean something different from what the audience understands.

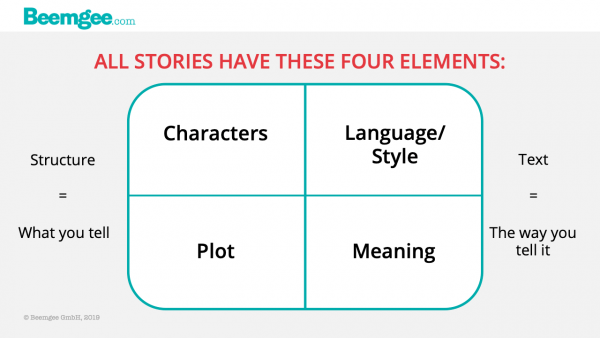

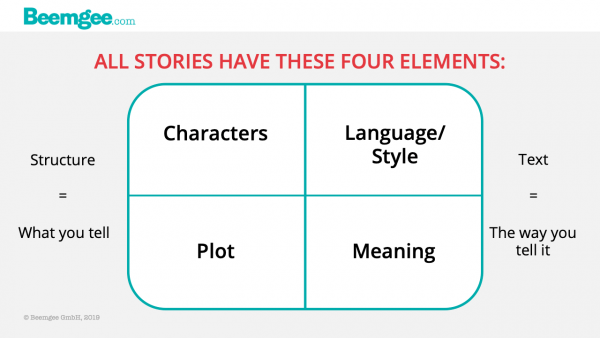

Let’s try to unravel this tricky but essential element of stories. We have noted that stories cannot help but exhibit four distinct elements:

- Characters

- Plot

- Style (aka language, or “voice”)

- Meaning

The interplay of characters and their actions form the plot, and all this is brought into a story structure, or narrative. Since there is always an author writing the novel or a team of people making the film, their stylistic choices determine the language of the work. In this post, we’ll skim the surface of the fourth element. Meaning is, of course, a broad term for something very hard to pinpoint.

We could add more story elements to the list. For instance, we have claimed that there is No Story Without Backstory. Furthermore, since the characters act within a time and place, there is always a story world. And in order to make the audience understand all this, there is always some measure of exposition. Then there is change or transformation, cause and effect, etc.

Let’s break down how we might look for the meaning of a story. (more…)

Archetypal Antagonism in Documentary Film and Fiction

by Amos Ponger of Mrs Wulf Story Consulting

Stories are intricate mechanisms

Documentary film is a powerful genre that draws much of its energy from the material of real-life action. Consuming documentaries, we as spectators often ignore the fact that documentaries, like fiction, are a constructed clockwork of storytelling. Since the digital revolution, the amounts of raw material for documentary productions have probably grown tenfold, shifting much of the dramaturgical construction work to the editing room. Dealing with hundreds of hours of material you may say that 90 percent of the editing work in documentary film is “finding the story“, discovering what your story is about.

One issue editors often encounter while working on the narratives of documentary films is that many directors tend to neglect the importance of understanding and designing their antagonist or their antagonistic powers, the Antagonism.

Sure, you love your protagonists. You identify with their strivings and journeys, and you as a storyteller have probably given a lot of thought to making them appealing to your audience, giving the audience someone they can identify with. Your protagonists may be an inspiration to you, or you may yourself strongly identify with them, you may share or appreciate some of their characteristics and values.

At the same time you have probably not given your Antagonist/m the same attention. Have you? (more…)

What is the difference between commissioning editors, developmental editors, and line editors?

Photo by Patrick Tomasso on Unsplash

Let’s look at what each do to see the differences between the three different kinds of editors. And then find the other editorial task they all have in common.

The Commissioning Editor

An example (more…)

How narrative structure turns a story into an emotional experience.

Image: Comfreak, Pixabay

Storytelling is a bit of an overused buzzword. While we are all – by dint of being human – storytellers, how aware are you of the principles of dramaturgy? What exactly constitutes a story, in comparison to, say, a report or an anecdote?

And just to be clear, the following is not a story. It’s an how-to article.

Whatever the medium – film or text, online or offline –, storytelling has something to do with emotionally engaging an audience, that much seems clear. So is a picture of a cute puppy a story? Hardly.

Stories exist in order to create a difference in their audience. Stories always address problems and tend to convey the benefits of co-operative behaviour.

While there simply is no blueprint to how stories work, let’s examine the elements that recur in stories and try to find some patterns.

Who is the story about?

All stories are about someone. That someone does not have to be a person, it can be an animal (Bambi) or a robot (Wall-e). But a story needs a character. In fact, all stories have more than one character, with virtually no exceptions. This is because the interaction between several characters provides motivation, conflict and action.

Moreover, stories usually have a main character, the figure that the story seems to be principally about – the protagonist. It is not always obvious why one character is the protagonist rather than another. Is she simply the most heroic? Is she the one that develops most? Or does she just have the most scenes?(more…)

Antje Tresp-Welte is the winner of the Your Perfect Plot challenge set by BoD and Beemgee.

In her guest blog post, she gives frank insight into her writing process and her experiences with Beemgee.

Short stories were child’s play

Short stories were child’s play

When something intrigues me, I spin a story out of it. Until a few years ago I wrote mostly fairy tales, short stories for adults, poetry and stories for younger children, some of which were published in magazines. My story about a bad-tempered spectacled snake was published as a little book, “Charlotte and the Blue Lurker”. For all these stories I only sketched a few thoughts as planning and then wrote them down relatively quickly.

By now, book projects fascinate me too. Currently they are crime novels and fantasy for children from 8 or 10 years.

Long takes longer …

During a holiday at the North Sea I had the idea for my first crime novel. In it, the protagonist, an eleven-year-old very imaginative boy with a penchant for drawing, not only saves his grandma’s tea room from demolition, but is also involved in a mysterious story about a pirate who died long ago. I developed the original idea into a plot at a seminar for authors. I found the topic so great that I couldn’t wait to start writing it. Beforehand, I made notes on the individual characters and considered important cornerstones of the plot with the help of the hero’s journey. I started off with a great momentum and was soon able to read the first chapters to my son. Unfortunately his comment was, “Mama, that is much too long!”

… not to be longwinded

My two test readers came to a similar conclusion and I too had noticed that it somehow “grated”. I wasn’t really getting to the point. Was it due to my preliminary planning? Was it not detailed enough? I dived into the text, shortened passages, removed individual characters and worked out others more precisely. This changed entire storylines. At the same time my story gained more (narrative) speed and I found the tone for the language. (more…)

Stories are driven by yearning.

In order to get somewhere, there has to be a current position and a destination. Stories fundamentally describe a change of state – things are different at the end of the story than at the beginning. Hence a story has a starting point and a final end point, a resolution.

But that’s not enough. There has to be fuel, energy to power the motion between the one position and the other. In stories, this driving force is the motivation of the characters.

Motivation is so important to storytelling that we are going to look at several aspects of it. We’ll break it down into what we call the wish, the want, and the goal, all of which are interlinked but also distinct from each other. Here in this post, we’ll deal with the wish.

A wish is inherent in the character from the beginning. We might call it a character want, as distinct from a plot want (which we deal with elsewhere).

Some examples: (more…)

What do we mean when we talk about story structure?

A story is a complex entity comprising many interrelating parts. The author imposes some sort of organising principle onto the material, turning the story into a narrative. The result of this forming or shaping of the material is the story structure.

Certain structural markers are so explicit that the audience is aware of them, such as chapters in novels. Elizabethan plays are typically divided into five acts. A film script is broken down into acts, sequences, and scenes.

The beat is the smallest unit of story, below the scene in the structural hierarchy. It is the space between an action and the reaction it causes within a scene.

- Beat

- Scene

- Sequence

- Act

- Story

A plot event is not part of this traditional hierarchy, being more of a meta-unit somewhere between beat and scene.

Scenes and acts are defined in screenplays, like chapters in novels. But stories have structures that are not usually made obvious or explicit.

Beats

There are two different understandings of the term beat.

A scene may be broken down into beats – marked only by the moments when the mood or relationship the scene describes changes. Two characters are having a conversation, character A says something which makes character B react in a different way from what A expected – that’s a beat.

The term beat is also sometimes used when marking such changes on a bigger scale, across an entire narrative. Some screenwriters work with so-called beat sheets; in the Beemgee outlining tool, the plot event cards are perfect for creating beat sheets, since each card is designed to stand for one plot event. In a beat sheet, a beat is one unit of plot. If you think of narrative as a chain of events, then each beat is a single link. In one school of thought, a Hollywood movie is ideally constructed of exactly 40 such beats. (more…)

The process of writing is unique to each author.

There is no right or wrong way to write a work of fiction. Perhaps the main thing is to just sit down and get on with it.

Many authors start by writing the beginning of the story and working their way through to the end. This seems intuitive, as it mirrors the way narratives are normally received – from opening to resolution. Furthermore, it allows a development of the material that feels natural, beginning probably with a setting and a character or two and growing in complexity as the story progresses.

But this isn’t the only way to get a story written. The author is not the recipient, after all. The author is the creator.

Creative habits seem to differ according to medium. Most screenwriters spend a lot of time working out the intricacies of plot and complexities of character before beginning to actually write the screenplay. Some novelists, on the other hand, seem to require the writing process in order to get to grips with the material. For such authors, the act of working on text is so intimately intertwined with the craft of dramaturgy that the shaping of the story has to be performed simultaneously with the writing of it.

Flow

In some cases, a writer might have a fairly clear idea in mind where the story is headed, or already be aware of certain key scenes that ought to be included. In others, the author may not know how the story ends(more…)

A plot arises out of the actions and interactions of the characters.

On the whole, you need at least two characters to create a plot. Add even more characters to the mix, and you’ll have possibilities for more than one plot.

Most stories consist of more than one plot. Each such plot is a self-contained storyline.

The Central Plot

Often there is a central plot and at least one subplot. The central plot is usually the one that arcs across the entire narrative, from the onset of the external problem (the “inciting incident” for one character) to its resolution. This is the plot that is at the(more…)

Events propel narrative. Narrative consists of a chain of events.

These do not have to be spectacular action events – they can be internal psychological events if your story is about a man who does not leave his room, or spiritual events if you are recounting the story of Buddha sitting beneath the tree. But events there must be if there is to be a story.

In this post we’ll discuss –

Events in a story are effectively bits of knowledge the author wants to impart – in a particular order, the narrative – to the recipient, i.e. the reader or audience. The story is told when all the pertinent knowledge has been presented, when all the bits of information necessary for the story to feel like a coherent unity are conveyed. An author(more…)

This may seem like a silly question. How long is a piece of string, right? And the simple answer is:

ideally, a story is as long as it needs to be, and no longer.

There are norms that have developed over time, and which are more or less inculcated into us due to our exposure to stories in their typical media. Back in the 1970s or 80s a music album contained a total of about 40 minutes of sound, because that is as much as would fit on a long-playing vinyl 33 rpm record, approximately 20 minutes on either side. With the advent of the CD, suddenly musicians felt the artistic need to create albums that were twice as long.

You’d think that stories wouldn’t be subject to such constraints because the carrier media for stories are more flexible. However, when it comes to moving pictures at least, what is typically considered a fair attention span to expect the audience to tolerate does seem prone to popular beliefs by industry players in the respective markets. For example, a typical feature length film is roughly two hours long. This is practical because cinemas can comfortably manage two screenings an evening. If the film is good enough, it could of course easily be longer, but at some point viewers become restless and need an intermission.

A typical two hour-ish movie has between forty and sixty scenes. Formatted according to industry standards, a screenplay has approximately as many pages as the finished movie would have minutes. In terms of plot events, some people in Hollywood believe that a commercial movie should have exactly forty (which in Beemgee’s plot outlining tool would mean exactly 40 event cards).

Content and form may be mutually determined, to some degree at least. A short story is usually considered such if it has less than 10.000 words. By dint of its length, a short story probably concentrates on one character’s dealing with one specific issue or occurrence, and is unlikely to have subplots or multiplots (that is, be about more than one protagonist).

Short stories are great practice for writers cutting their teeth. Our friends at the self-publishingschool have gathered 11 Easy Steps for Satisfying Stories.

A piece of written prose fiction between 10.000 and 50.000 words is often considered a ‘novella’. This is a sort of hybrid between the short story and the novel. The narrative of a novella is likely to cover more ground – that is, relate a longer and more complex set of events – than a short story simply because it is longer than a short story. But to state that a novella perforce has more depth or more action than a short story would be a meaningless generalization. What is likely is that the focus in a longer narrative such as a novella is on a string of occurrences (or chain of events, i.e. causally linked events) rather than the story revolving around the meaning and effects of a single occurrence. (more…)

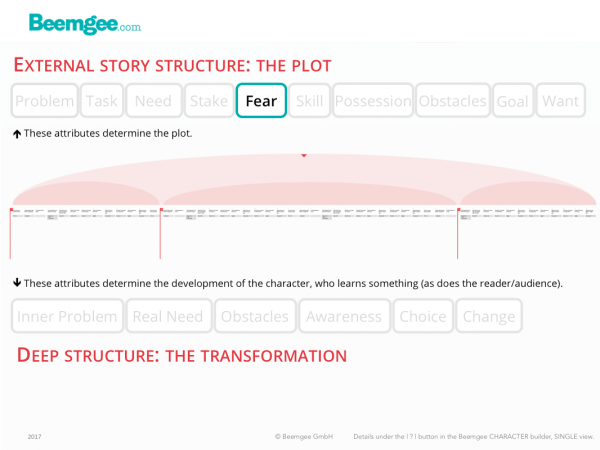

Certain universals are feared by almost everyone. Such as death.

If a character in a story has loved ones, losing them is an even stronger fear.

A story engages the audience or readers more strongly when there is something valuable at stake for the character, such as his or her own life or that of a loved one. So giving a character a universal fear is usually a good place to start.

Giving a character a specific fear to overcome requires this information to be placed early in the narrative. The fear is then faced at a crisis point in the story, usually the midpoint or the climax.

Characters can have specific fears. A fear which is specific to one character must be set(more…)

It’s the way you tell it.

Narrative is the choice of which events to relate and in what order to relate them – so it is a representation or specific manifestation of the story, rather than the story itself. The easy way to remember the difference between story and narrative is to reshuffle the order of events. A new event order means you have a new narrative of the same story.

Narrative turns story into information, or better, into knowledge for the recipient (the audience or reader). Each story event is a unit of knowledge the audience requires.

A narrative is paradox, because it seeks to convey truth by hiding it. A storyteller arranges the items of knowledge in such a way that they are revealed gradually, which implies initially obscuring the truth behind what is told. Such deliberate authorial obfuscation creates a sense of mystery or tension, and creates a desire in the audience to find out what is happening in the story and why. In this sense, a narrative is effectively the opposite of an account or a report.

A report presents information in order to be understood by the audience immediately, as it is being related. A neutral, matter of fact presentation probably maintains a chronology of events. It explains a state of affairs blow by blow, and aims for maximum clarity at every stage. It seeks to convey truth by simply telling it. While the point of a narrative is also that the recipient perceives the truth of the story, in a narrative this truth is conveyed indirectly. Narrative is therefore responsible for how the recipient perceives the story.

In this article we’ll look at

- Story Basics

- The Components of Story

- Text Types That Describe A Story

- Author Choices: Genre and Point of View

- Causality in Narrative

Story Basics

First, let’s state some basics as we understand them here at Beemgee: a story consists of events that are related by a narrator; events consist of actions carried out by characters; characters are motivated, they have reasons for the things they do; there is conflict involved; one and the same story may be told in different ways, that is, have varying narratives.

Note that we are talking here about narrative in the dramaturgical sense – not in the social sense. Like the term “storytelling”, the word “narrative” has become a bit of a buzzword. We are not referring here to open “social narratives” such as “the American narrative”. For the definition and exploration of such collective narratives, see our article in The Bigger ‘Narratives’ of Society. Here, we are pinpointing the use of the term primarily for storytellers creating novels, films, plays, and the like. Such works tend in their archetypal form to be closed narratives with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

A narrative may present the events of the story in linear, that is to say chronological order or not. But the story remains the story – even if it is told backwards.(more…)

Narrative is made of successive events. Not necessarily in the order they occurred.

Narrative is the order in which the author presents a story’s events to the recipient, i.e. the audience or reader. Chronology is the order of these events consecutively in time. Some people use terms from Russian Formalism, Syuzhet and Fabula, to make the distinction.

A chronology usually has less emotional impact than a narrative – essentially a chronology is recounting a report whereas a narrative is telling a story. In a chronology, the plot events are lined up in temporal sequence. You could say “and then” between each event. In a narrative, the emotional effect is closely related to the causality implied by the arrangement of the events. Between each event you could say, “because of that …”.

Narrative therefore carries with it the implication of understanding. The juxtaposition of events, for example, will create associations in the audience’ minds that lead to possibilities of interpretation. While a chronology may explain things, it is in itself inherently neutral. Narrative on the other hand is an arrangement that is usually consciously made by an author who intends something by the particular arrangement, and which, independently of author intention, is subject to interpretation by recipients.

While the convention in most storytelling is linear, i.e. to relate the story’s events consecutively in time (chronologically), we as audiences and storytellers are also very used to narratives that move certain events around. An event may be moved forward, meaning towards the beginning of the narrative, perhaps even to be used as a kick-off. Or possibly events may be withheld from the audience or reader and pushed towards the end, perhaps to create a reveal late in the narrative for a surprise effect – though this technique often feels cheap. Also, an author may use flashbacks to insert backstory events from the past, the past being all relevant events that take place before scene one in the narrative.

As authors, when we begin composing a story, we(more…)

Inventing a story that has no backstory is about as easy as finding a perfect rhyme for the word orange.

That is, next to impossible.

Backstory is the stuff that went on before the story begins, or more precisely, before the kick-off event in scene 1. As such, backstory might better be called “pre-story”. It is a necessary component of any story.

After all, the characters come from somewhere – they have pasts, they have histories. These histories have shaped them into who they are, which determines their actions now, in the time of the story. These actions are the source of the events of the story. So some part of the characters’ histories will be relevant to the story – and this bit of information or knowledge needs to be passed on to the audience or reader. That’s why so many stories have “campfire scenes”, a moment of calm usually near the beginning of the second half during which characters recount stories of their pasts to each other. (more…)

Narrative consists of successive events.

One recognizable convention from film is what we might call the kick-off event. It is the opening scene, the very first item in the narrative. This is not to be confused with the inciting incident.

We’ll refer to the kick-off event as the initial scene, and whatever the medium – page, stage, or screen – it ought to capture the audience’s or reader’s attention.

The kick-off event can be drawn from virtually anywhere in the event chronology – like a “capsule” of plot pulled out from the narrative (more on that below). It may open up some questions to arouse our curiosity, or tell us something about a major character that will become relevant much later. It can throw the audience or reader, the recipient of the story, in medias res, straight into the middle of an exciting event. Or it can build up slowly to set the scene and establish a mood.

This first event(more…)