When the bad guy makes the hero’s journey difficult.

Let’s say your hero or heroine is a falsely accused fugitive from the law. While on the run, every policeman or government agent is effectively an antagonistic obstacle. This is particularly the case if there is a specific character who represents the state and whose mission it is to catch the heroine. This detective or agent casts out the net to catch the fugitive, using all the instruments of the state at his or her disposal in order to actively thwart the heroine’s escape.

Or maybe your story is about a soldier behind enemy lines on a mission to find and destroy (or steal) the enemy’s new super weapon, or perhaps rescue an important person who has been captured. Any enemy soldiers the hero encounters are, of course, obstacles. One could say that they are external obstacles if they just happen to be there, like a patrol unit. But if there is on the enemy side a character who is aware of our hero’s approach and is actively seeking to stop him achieving his mission, then the soldiers and/or henchmen this character sends out to find the hero are not external obstacles but antagonistic obstacles.

As we have said before, this division into three classes of obstacles – internal, external, and antagonistic – is not cut and dried and need not be followed too strictly. But differentiating between the different kinds of obstacles a hero or heroine must face while designing and planning your story can lead to a more exciting plot, simply because you can disperse the obstacles systematically within the story journey and have all the different kinds of obstacle build up to a great crescendo at the climax. (more…)

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that Writer.com approached us to talk about character development. While their speciality is AI-assisted text generation for companies, in their guest post, they have some good general advice on creating fictional characters. Thanks to Nicholas Rubright for this article. Nickolas is a digital marketing specialist and expert at Writer. In his free time, he enjoys playing guitar, writing music, and building cool things on the internet.

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that Writer.com approached us to talk about character development. While their speciality is AI-assisted text generation for companies, in their guest post, they have some good general advice on creating fictional characters. Thanks to Nicholas Rubright for this article. Nickolas is a digital marketing specialist and expert at Writer. In his free time, he enjoys playing guitar, writing music, and building cool things on the internet.

Writing characters with whom readers can identify and empathize should be the goal of every writer, but it’s not a simple task.

To fully grasp a character’s motivations, desires, and anxieties, writers must dive deep into the character’s psyche. Character flaws and strengths work together to build a solid character.

But what is the most effective way to develop a character? And how can you establish a connection between your character’s dramatic decisions and the story itself?

Your characters are the heart and soul of your story. Thus, before you can write a single word, you must first understand your characters.

When it comes to character creation, you have several choices to make, and each choice affects the story in its own way. You must, however, choose what works best for your character.

While an unexpected detail can make the character more interesting, if it isn’t chosen carefully it can damage the character’s believability and ruin your reader’s immersion in your story.

Here are some guidelines and tricks to help you successfully create mouldable character templates for your story.

So, let’s dive in! (more…)

Universal storytelling principles behind the most successful movie series ever.

The sumptuous music of John Barry, the stunning set designs of Ken Adam, the directorial skills of Terence Young or Guy Hamilton, the innovative editing of Peter Hunt, the screen presence of Sean Connery, the zangy theme tune by Monty Norman, memorable actresses, spectacular stunts, and exotic location scouting – a fortunate convergence of individual talents built up the abiding popularity of Ian Fleming’s literary creation, the British MI6 agent James Bond.

Most writers don’t have access to such a talent pool, nor do most authors write action-packed spy capers. Also, 007 stories in particular seem so specific a category that authors might not consider that their own works have much in common with them. So one might be tempted to think that most writers can’t learn anything useful from James Bond.

Many people say there is a James Bond formula. Guy Hamilton, director of four of the early Bond movies, has said not. But there are certainly recurring scene types and structural elements that bear examination. A closer look reveals at least seven dramaturgical principles that any author could consider applying.

- The Kick-off Event

- The Real Reason for M

- The Real Reason for Q

- A Timely Death

- The Antagonist

- Revelation and Confrontation

- Humps

(more…)

Nothing should be more important to an author than how their story makes the audience feel.

As an author, consider carefully the emotional journey of the reader or viewer as they progress through your narrative.

The audience experiences a sequence of emotions when engaged in a narrative. So narrative structure is a vital aspect of storytelling. The story should be touching the audience emotionally during every scene. Furthermore, each new scene should evoke a new feeling in order to remain fresh and surprising.

The author’s job is to make the audience feel empathy with the characters quickly, so that an emotional response to the characters’ situation is possible. Only this can lead to physical reactions like accelerated heartbeat when the story gets exciting. We have to care.

This “capturing” of the audience, making the reader or viewer rapt and enthralled, requires authors to create events that will show who the characters are and how they react to the problems they must face. The audience is more likely to feel with the characters as the plot unfolds when the characters’ reactions to events reveal something about who they really are – and how they might be similar to us.

One Journey to Spellbind Them All

Here we present a loose pattern that we think probably fits for any type of story, whatever genre or medium, however “literary” or “commercial”. It’s not prescriptive, just a rough checklist of the stages in the emotional journey the audience tacitly expects when they let themselves in on a story. The emotions are in more or less the order they might be evoked by any narrative.

Curiosity

(more…)

Guest Post by KT Mehra.

KT Mehra knows a thing or two about writing from her own experience, not only as an author but as a supplier to writers and authors of fine stationary, in particular fountain pens. Not only that, she is digital savvy too.

Back in 1999, KT and her husband Sal started a small web company to create websites for local businesses and provide internet access. They both had a passion for fountain pens, and one day KT, in an excess of enthusiasm, ordered far too many from a pen company. Just for fun, she decided not to return any of them and instead asked her team to design an e-commerce website to sell the extra pens.

To everyone’s surprise and just like that, the website came together quickly and was an instant success.

KT believes that in the modern digitally saturated world, it’s more important than ever to stay true to your thoughts and create something tangible. In that spirit of creation, she feels that something as elemental as putting pen to paper is ever more essential.

Despite offering a digital tool for authors, we couldn’t agree more!

Develop a romantic relationship that your readers will engage with and root for.

Most of the romance novels you love so much use certain secrets to hook their readers in and keep them engaged.

Learning the secrets to create such compelling romance novels will help you perfect your characters’ love story.

The Basics

The best way for your readers to relate and root for your relationship is for you to make it realistic and dynamic. To build the foundation of any great love story, you need to have a few things down first. (more…)

Stories tend to show characters getting together.

Stories don’t get going until there are at least two characters.

That’s because the characters in themselves are not really what interests the audience. What the audience likes to experience is relationships.

At a fundamental level, there are only these three ways that people – or characters within a story – can interact with each other:

- they can cooperate

- they might oppose each other

- or they may get together

It is the complexities of these types of relationship that authors present to their audiences.

At least two of the three types of relationships are likely to be depicted in any story, cooperation and conflict. To make the story feel complete, authors especially of popular stories such as Hollywood movies often include the third type in the form of a love interest. (more…)

Three sorts of opposition, and two things to remember.

Opposition causes conflict

For any character in a story, there may be opponents, not just for the protagonist. So while the protagonist-antagonism struggle may be at the forefront of the story, actually there is a whole system of opposing forces.

Let’s examine how characters in stories work against each other.

- Opposition can come from striving for the same or for opposite ends.

- Opponents can be antagonistic or incidental.

- There are two sorts of opponents, those from without, and those from within.

Same same or different?

An author might take each character at a time and arrange their opponents, which means characters who are either trying to get to the same thing first or whose success in attaining something else would thwart the character’s efforts.

In other words, the opposition (unless it arises by chance, see below) takes the form of either competition or threat. Competition for the same goal: Who will reach the South Pole first? Threat, because the goal of the opponent is opposed to the goal of the other figure: a nature reserve or a hotel complex. Imagine this for yourself using your own example: Your opponents strive for the same goal as you, and if your competitor wins, you get nothing. So your opponents are competing with you for the same goal, for example the same person. Or your opponent wants something completely different from you, and if he achieves that, it means you cannot get what you want. The success of the opponent is therefore a threat to your own well-being.

In either case, the opposition may be … (more…)

A plot arises out of the actions and interactions of the characters.

On the whole, you need at least two characters to create a plot. Add even more characters to the mix, and you’ll have possibilities for more than one plot.

Most stories consist of more than one plot. Each such plot is a self-contained storyline.

The Central Plot

Often there is a central plot and at least one subplot. The central plot is usually the one that arcs across the entire narrative, from the onset of the external problem (the “inciting incident” for one character) to its resolution. This is the plot that is at the(more…)

In essence, there are three kinds of opposition a character in a work of fiction may have to deal with:

- Character vs. character

- Character vs. nature

- Character vs. society

However, this way of categorising types of opposition is not equivalent to internal, external and antagonistic obstacles. Any of the three kinds of opposition listed above may be internal, external, or antagonistic. It depends on the story structure.

External opposition

In any story, the cast of characters will likely be diverse in such a way as to highlight the differences and conflicts of interests between the individuals. In some cases, certain roles may be expected or necessary parts of the surroundings, i.e. of the story world. In the story of a prisoner, it is implicit that there will be jailors or wardens, whose interest it will be to keep the prisoner in prison, which is in opposition or conflict with the prisoner’s desire for freedom.(more…)

In stories, characters are faced with obstacles.

These obstacles come in various forms and degrees of magnitude. And they may have different dimensions: they may be internal, external, or antagonistic.

Often the obstacles that resound most with a significant proportion of the audience are the ones that force the main characters to face and deal with problems within themselves, in their nature. In other words, with their internal problem.

Internal obstacles are the symptoms of the characters’ flaws or shortcomings, i.e. of the internal problem. The audience perceives them in scenes in which the character’s flaw prevents her progress.

Not every story features characters with internal problems. An internal problem is not strictly speaking necessary in order to create an exciting story.

But it helps.

The Emotional Truth

An internal problem makes the character appear fallible – and thus more credible, more human, more like us. Internal problems are invariably emotional and private. They express(more…)

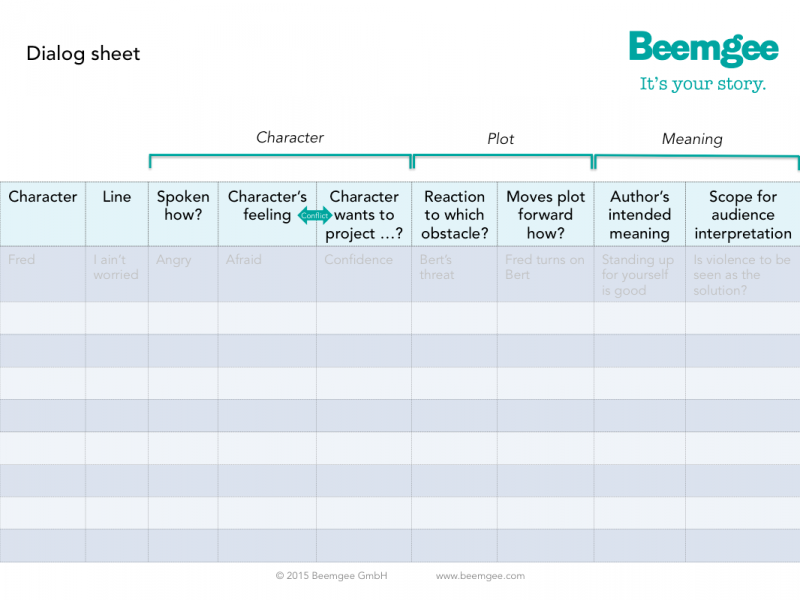

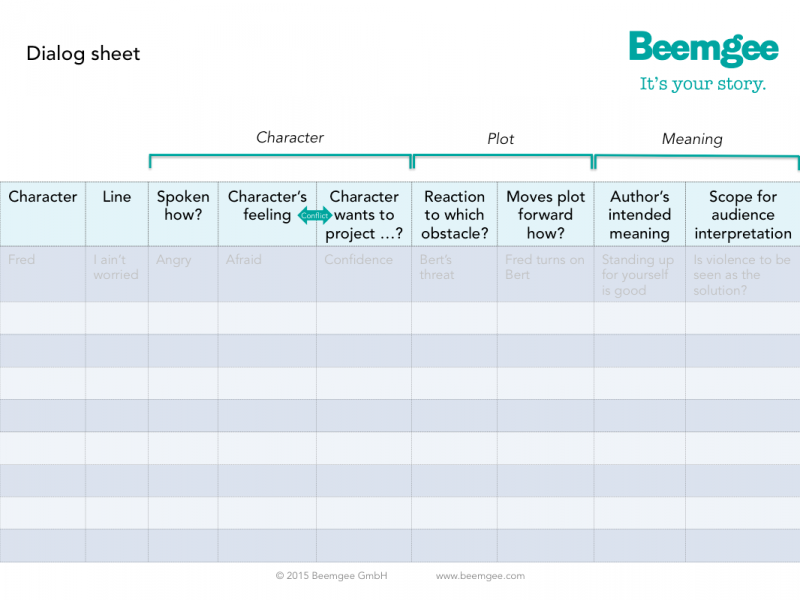

The seven elements of every line of dialog in a story.

Dialog enlivens stories. But dialog in stories is very different from real spoken language. It conveys information that the audience needs to know in order to understand the story as well as the characters – the one speaking the lines as well as the one reacting to them.

There is the rule of thumb that it’s better for the author to use action to explain things or move the plot forward than dialog, at least in film. Certainly, when the author makes characters say things solely to convey some bit of knowledge to the audience or reader, the lines tend to feel false. That’s a form of exposition, explanatory stuffing. If in doubt, leave it out. You’ll be surprised how much the audience understands even without explanations.

On the other hand, Elmore Leonard noted how readers don’t usually skip dialog. People like dialog. Dialog can be exciting. Dialog can be action. So authors had better know how to write it.

Here are seven things you ought to consider about every single line of dialog you put into your characters’ mouths. We’ve created this free table to help you. Feel free to download, use and share it.

1

If you’re writing(more…)

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that

Here at Beemgee, we’re into the thought behind the writing of stories more than the writing itself. So we’re all the more pleased that