A story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. How to avoid the ‘saggy middle’.

The middle bit of a story is really the story proper. It is usually the longest section. It comes after the introduction of the main character(s) and the setting up of the context, that is the world of the story, as well as the problems and themes the story deals with.

At the end of the first section – prior to what we’re here calling ‘the middle bit’ –, the protagonist has decided to set off on the story journey. Obviously, this does not have to be physical journey through a particular geography, but it does mean that the main character is somehow entering into new and unfamiliar terrain. In this sense, every story is a ‘fish out of water’ story. The heroine must leave the comfort zone in order for the audience to feel interest in her plight.

Some authors jump right into this unfamiliar territory, showing the run up to it in flashbacks. Anita Brookner’s heroine Edith Hope has already arrived in the Hotel du Lac in the first sentence of the novel. Gradually the reasons for her stay here are revealed as the reader progresses through the novel.

Nonetheless, for an author, it may be advisable to create a marked threshold where the protagonist enters into the alien territory of the middle bit. The exploration and transversal of this territory is what on a plot level the middle bit is about, and it takes up the greater part of the story journey. (more…)

The midpoint is structurally the most significant point in a narrative.

Given that stories have a tendency to symmetry, the centre of a narrative should mark the zenith of the story arc, and with that, the pivotal point of the story.

So, to get to (mid)point: What happens in the middle of a story?

Here are some typical midpoint events:

- Something searched for is found (Star Wars IV, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lolita)

- A hidden truth is unveiled (to the audience, at least) – if not yet understood (Matrix, Pride and Prejudice, The Gruffalo)

- A dramatic event thwarts all plans made hitherto (James Cameron’s Titanic)

The centre of the narrative may be the discovery of something missing – in crime stories a vital piece of the puzzle may be revealed here (either to the audience or to the audience as well as the protagonist).

In any genre or dramatic category, the midpoint may be a moment of truth. This might be just a clue for the audience or perhaps an initial revelation of the true state of things.

If a character realises or finds out something that has so far been hidden, then this is the point at which the character begins to gain awareness. This counts in particular for the recognition of the character’s own internal problem. From here on the story might possibly lead up to a moment of choice at the crisis, when it becomes clear to the audience whether the character has learnt from this new awareness or not. In other words, the real need begins to overcome or supplant the character’s initial want due to what happens at the midpoint.

Some well-known examples of the midpoint

(more…)

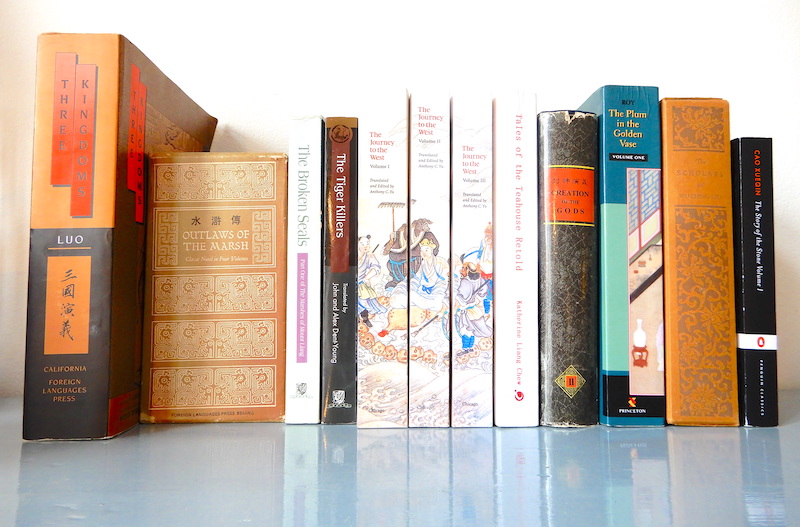

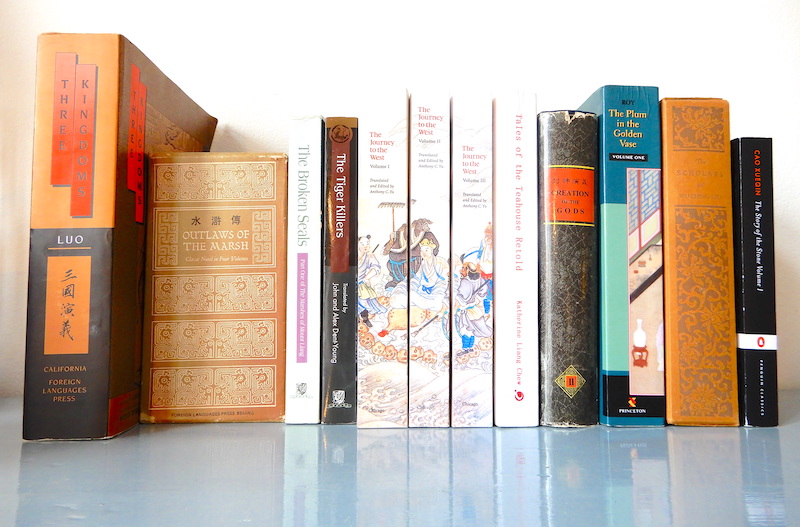

Take a look at your book shelf. Chances are there are European and North American authors there. Perhaps you have some Central or South American writers too. And maybe some Indian or Pakistani novels. And perhaps some Russians.

All of these authors wrote or write in the tradition of European storytelling, via colonial or cultural influence. Modern African authors writing novels, for example, have adopted this written prose text form although African storytelling traditions are primarily oral.

What most of us, at least in the western world, know about how to tell stories is influenced heavily by Aristotle’s Poetics. In this rather thin book, Aristotle describes some basic precepts of dramatic composition that continue to be circulated in creative writing classes and how-to books today.

Another strong influence on western storytelling is the protagonist/antagonist duality which arose along with Christianity. Would there be a Sauron without Satan? A Darth without the Devil? A Voldemort without Lucifer?

So what about stories that were created without any knowledge of Aristotle or Christianity? How are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different?

Let’s find out by asking … (more…)

The protagonist is the main character or hero of the story.

Photo by Jack Moreh on Freerange

But “hero” is a word with adventurous connotations, so we’ll stick to the term protagonist to signify the main character around whom the story is built. Sometimes it is not so easy to know which is your main character.

Generally speaking, the protagonist is the character whom the reader or audience accompanies for the greater part of the narrative. So usually this character is the one with most screen or page time. Often the protagonist is the character who exhibits the most profound change or transformation by the end of the story.

Furthermore, the protagonist – and in particular what the protagonist learns – embodies the story’s theme.

For simplicity’s sake, let us say for the moment that in ensemble pieces with several main characters, each of them is the protagonist of his or her own story, or rather storyline. Since the protagonist is on the whole a pretty important figure in a story, there is a fair bit to say about this archetype, so this post is going to be quite long.

In it we’ll answer some questions:

- Is the protagonist the most interesting character in the story?

- What are the most important aspects of the protagonist for the author to convey?

- What about the transformation or learning curve?

How Interesting Must The Protagonist Be?

Some say the protagonist should be the most interesting character in the story, and the one whose fate you care about most.

But while that is often the case, it does not necessarily have to be true.

(more…)

In stories, the characters’ emotions are ultimately the sources of their actions, because motivations are ultimately based on emotions.

Determining the emotional core of a character in a story may lead to a clearer understanding of that character’s behaviour, i.e. their actions.

What we’re getting at here is essentially a premise for creating a story. We have noted that if you plonk a group of contrasting characters in a room – or story-world –, then a plot can emerge out of the arising conflicts of interest. If you’re designing a story, one approach is to create the contrasts between the characters (their essential differences of character) by giving each character a core trait or emotion. One character may be frivolous, another penny-pinching. One may be fearful, another cheeky.

You might object: Isn’t that a bit one-dimensional? Aren’t characters with just one core emotion flat?

Not necessarily. Focusing on one core emotion is not a cheap trick. It is as old as storytelling.

Classical Storytelling

Ancient(more…)