How perceptive a character is of her surroundings may have dramaturgical relevance.

A character who is good at noticing small details may make a good spy or detective, so if you are developing a detective or spy you may want to give your character this ability. But whatever your character’s profession, stop at least once per scene and ask yourself,

What is a detail that only this character might notice?

Why is this important? Because their perceptions can make characters more interesting and vivid.

If a certain plot event hinges on a character perceiving some small detail or other, it may be a good idea to plant a foreshadowing moment long before the scene, to heighten the impact of the act of perception.

Furthermore, a character’s perception may influence how your audience understands and enjoys the entire story. How exactly depends on two important factors:

- narrator

- point of view

(more…)

What a character might know that others don’t – including the audience

Some characters have secrets. We are not necessarily talking about their internal problem or the need that arises out of it (they may be aware of such a problem or not.) We are talking about information that makes a difference to the story once it is shared.

Character secrets are intimately bound to the scene type called a reveal (which does not necessarily have to entail a revelation).

In terms of story (or rather the dramaturgy of the story), if a character has a secret that is never revealed, the secret is irrelevant. Only if the secret is made known at some point in the narrative does it really exist as a component of the plot.

For authors, the main aspects of character secrets to control are:

- What plot event brings the secret about (this may be a backstory event)?

- How does the secret alter or determine the character’s decisions or behaviour?

- Does the character share the secret with another character at any point, and if so when (in which scene)?

- At what point in the narrative (in which scene) does the audience receive knowledge of this secret?

Who are you, really?

If it is so important the character has a secret, then, often, the secret becomes part of who this character is. Their role in the story, their identity within the story, is determined by their secret. So secrets are dramaturgically important. (more…)

If a story is your original idea, then the copyright to it is by default yours.

However, copyright is a complex legal issue we cannot hope and don’t even want to explain properly here.

Each country has its own copyright laws. Also, copyright usually doesn’t apply until there is a pretty concrete manifestation of a “work”. It is easier to establish the copyright of the text of a novel than of the story the novel recounts. A story idea or even a fairly detailed outline may not qualify for legal copyright. But if you have a project in the form of a detailed outline which has a date to it, you have at least a way of asserting your moral rights to the intellectual property. (more…)

The logline is probably the hardest sentence to write.

The logline sums up a story in one sentence. This sentence should be memorable and clear, which means it is unlikely to be much longer than thirty words or to have complex syntax.

Once your reader has read your logline – or your listener heard it –, they will ideally know the following about your story:

- who it is about

- what the central conflict or main problem is

- what the most important characters do in the story

- why they do it, i.e. what their motivations are

- how they do it

- where all this happens, i.e. what the setting is

- when it happens, i.e. what the period is

The first of these points even counts double – since usually the logline should convey not only who the main protagonist is, but also what antagonism she faces.

What’s the logline for?

The purpose of the logline is to pitch your story.(more…)

Conflict is the Lifeblood of Story.

In real life, conflict is something we generally want to avoid. Stories, on the other hand, require conflict. This discrepancy is an indicator of the underlying purpose of stories as a kind of training ground, a place where we learn to deal with conflict without having to suffer real-life consequences.

In this post we will look at:

- An Analogy

- Archetypal conflict in stories

- Conflict between characters

- Conflict within a character

- The central conflict

Along with language (in some form or other, be it as text or as the language of a medium, such as film) and meaning (intended by the author or understood by the recipient), characters and plot form the constituent parts of story. It is impossible to create a story that does not include these four components – even if the characters are one-dimensional and the plot has no structure. However, it is formally possible to compose a story with no conflict.

It just won’t be very interesting.

In terms of narrative, conflict is presented as a series of confrontations of increasing intensity. If there are no confrontations – no battles of wits or fists, no crossing of swords or sparring with words – there is little to hold the audience’ attention. To create confrontations, there must be at least a of conflict of interest between the characters.

Conflict does not occur at particular points in a story. It permeates the whole of it. It expresses the values transported by the story’s theme. It creates at least two options of choice, both of which must appear to some extent reasonable and justifiable to the protagonist, particularly at the moment of crisis.

(more…)

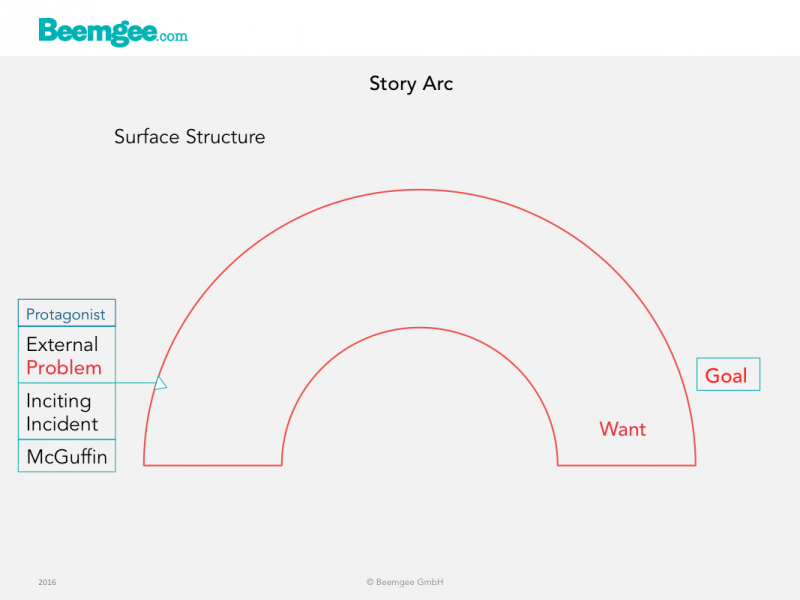

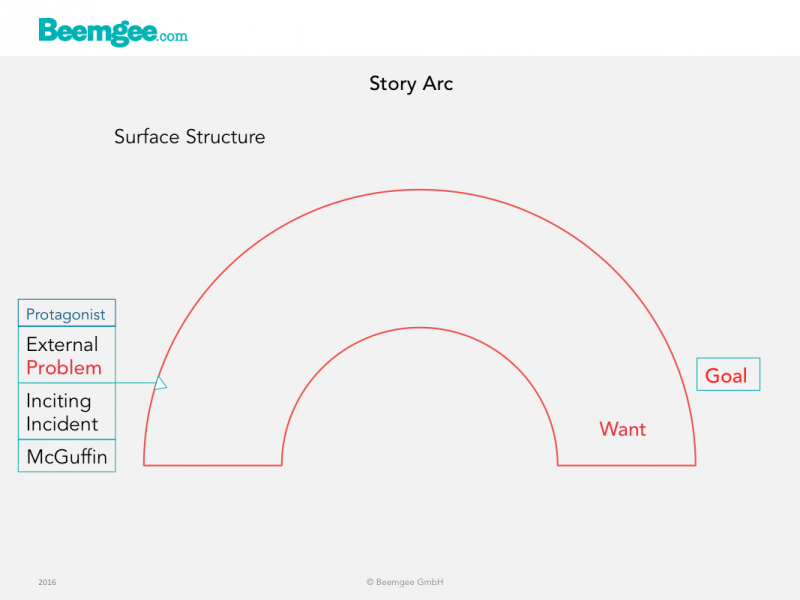

In storytelling, a McGuffin (or MacGuffin) is something that the protagonist is after – along with most other characters in the story.

The use of a McGuffin is a device the author employs in order to give a story direction and drive.

Easy to spot McGuffins are the Ark of the Covenant in Raiders Of The Lost Ark, the statuette in The Maltese Falcon, private Ryan in Saving Private Ryan, the ring (more specifically, the act of its destruction) in Lord Of The Rings. Note how in these examples, the McGuffin is in the title of the story. The McGuffin is embedded in the narrative structure and becomes what the story is about, on the surface at least.

Typical genres that have McGuffins are comedy, crime, adventure, fantasy and other quest stories. But conceivably, a dressed up McGuffin might be found in any genre.

Nor does a McGuffin have to be an object. It could be a person or a quality. In a story of several characters vying for the love of one other character, that love might be considered the McGuffin. A place might become a McGuffin too – consider the role of the planet Earth in Battlestar Galactica.

In terms of narrative structure, a McGuffin occupies the(more…)

Theme is a binding agent. It makes everything in a story stick together.

To state its theme is one way of describing what a story is about. To start finding a story’s theme, see if there is a more or less generic concept that fits, like “reform”, “racism”, “good vs. evil”. The theme of Shakespeare’s Othello is jealousy.

Once this broadest sense of theme is established, you could get a little more specific.

The theme is the expression of the reason why THIS story MUST be told! The theme of a story holds it together and expresses its values.

Theme may therefore be seen as an implicit message. But make sure that the message remains implicit, allowing the audience to understand it through their own interpretation.

Since a theme is usually (though not always) consciously posited by the author, it has some elements of a unique and personal vision of what is the best way to live. At best, this is expressed through the structure of the story, for instance by having the narrative culminate in a choice the protagonist has to make. The choices represent versions of what might be considered ways to live, or what is “right”.

But beware! This is a potential writer trap. See below.

How story expresses theme

Theme is expressed, essentially, through the audience’s reaction to how the characters grow. A consciously chosen theme seeks to convey a proposition that has the potential to be universally valid. Usually – and this is interesting in its evolutionary ramifications – the theme conveys a sense of the way a group or society can live together successfully.(more…)

It’s the way you tell it.

Narrative is the choice of which events to relate and in what order to relate them – so it is a representation or specific manifestation of the story, rather than the story itself. The easy way to remember the difference between story and narrative is to reshuffle the order of events. A new event order means you have a new narrative of the same story.

Narrative turns story into information, or better, into knowledge for the recipient (the audience or reader). Each story event is a unit of knowledge the audience requires.

A narrative is paradox, because it seeks to convey truth by hiding it. A storyteller arranges the items of knowledge in such a way that they are revealed gradually, which implies initially obscuring the truth behind what is told. Such deliberate authorial obfuscation creates a sense of mystery or tension, and creates a desire in the audience to find out what is happening in the story and why. In this sense, a narrative is effectively the opposite of an account or a report.

A report presents information in order to be understood by the audience immediately, as it is being related. A neutral, matter of fact presentation probably maintains a chronology of events. It explains a state of affairs blow by blow, and aims for maximum clarity at every stage. It seeks to convey truth by simply telling it. While the point of a narrative is also that the recipient perceives the truth of the story, in a narrative this truth is conveyed indirectly. Narrative is therefore responsible for how the recipient perceives the story.

In this article we’ll look at

- Story Basics

- The Components of Story

- Text Types That Describe A Story

- Author Choices: Genre and Point of View

- Causality in Narrative

Story Basics

First, let’s state some basics as we understand them here at Beemgee: a story consists of events that are related by a narrator; events consist of actions carried out by characters; characters are motivated, they have reasons for the things they do; there is conflict involved; one and the same story may be told in different ways, that is, have varying narratives.

Note that we are talking here about narrative in the dramaturgical sense – not in the social sense. Like the term “storytelling”, the word “narrative” has become a bit of a buzzword. We are not referring here to open “social narratives” such as “the American narrative”. For the definition and exploration of such collective narratives, see our article in The Bigger ‘Narratives’ of Society. Here, we are pinpointing the use of the term primarily for storytellers creating novels, films, plays, and the like. Such works tend in their archetypal form to be closed narratives with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

A narrative may present the events of the story in linear, that is to say chronological order or not. But the story remains the story – even if it is told backwards.(more…)