Today’s guest post is by writer Jason Brick. He has published his work in all sorts of genres and formats, with over 3000 articles, short stories, novels and non-fiction to his name – and about 20 books which are not, because he has ghost-written them. Jason also edits and crowdfunds anthologies. Next to writing, Jason loves martial arts and travel. We’re happy Jason has taken the time to explain flash fiction for us.

Today’s guest post is by writer Jason Brick. He has published his work in all sorts of genres and formats, with over 3000 articles, short stories, novels and non-fiction to his name – and about 20 books which are not, because he has ghost-written them. Jason also edits and crowdfunds anthologies. Next to writing, Jason loves martial arts and travel. We’re happy Jason has taken the time to explain flash fiction for us.

There’s an old saying. Every novelist is a failed short story writer, and every short story writer is a failed poet. I don’t know how much I believe that, but the adage leaves out another genre: flash fiction.

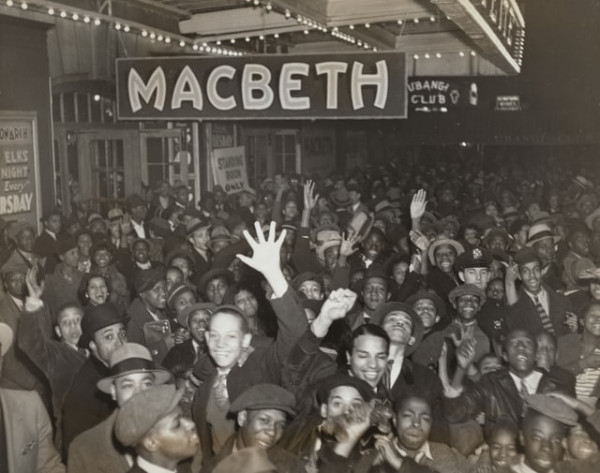

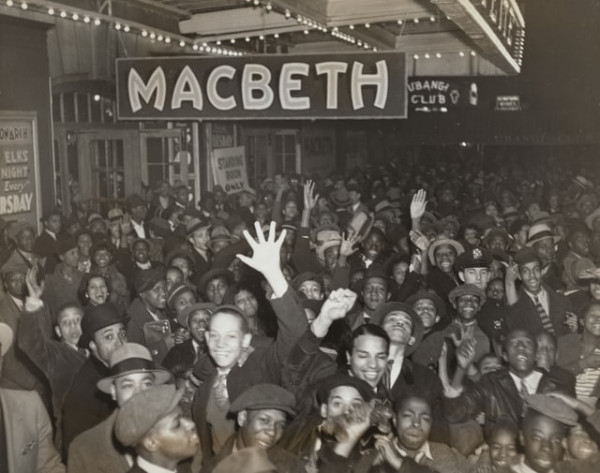

Depending who you ask, flash fiction refers to fiction in the 5,000 words or fewer range, with most falling more into the under-2,000 category. A famous example is attributed to Hemingway, consisting of just six words:

“For Sale: Baby shoes. Never used.”

If you ask some folks, they’ll give you all kinds of subdivisions. A “drabble” is 100 words or so. A “fragment” is under 50….that’s all well and good, but really flash fiction is simply super-short tales.

I like flash fiction so much I started a semiweekly newsletter that sends super-short stories to mailboxes all over the world. It’s called Flash in a Flash. We use a cutoff of 1,000 words, are always accepting submissions, and have come here today to chat about why flash fiction is fun, why authors might want to try some, and some places you can get started when you do. (more…)

Mastering Non-Linear Narratives in Modern Storytelling.

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.

In an era where storytelling transcends traditional boundaries, non-linear narratives have emerged as a potent device in the hands of a skillful storyteller. At once complex and captivating, these narratives challenge the time-honored sequence of beginning, middle, and end, engaging audiences with their intricate tapestries of time, memory, and perspective. From the labyrinthine plots of modern novels to the time-bending twists in contemporary cinema, mastering non-linear narratives demands a particular set of storytelling skills. In this article, we delve into the mechanics and artistry that enable modern storytellers to navigate the twists of time adeptly.

Defining Non-Linear Narratives

Non-linear storytelling is characterized by a plot that doesn’t follow a direct causality pattern, a chronological sequence of events, or both. It often involves flashbacks, flash-forwards, and other temporal leaps that demand a higher level of engagement from the audience as they piece the story together.

The Mechanics of Time Manipulation

Mastering the non-linear form requires a deep understanding of the story’s timeline. A storyteller must know the chronological sequence of events, even if the audience will never see the story this way.

Crafting the Jigsaw

In building a non-linear story, think of the narrative as a jigsaw puzzle. Each scene is a piece that, when connected to the broader picture, contributes to the overall story. The order in which these pieces are revealed is crucial in developing suspense, mystery, and dramatic irony. (more…)

The stories we tell each other collectively – sorting out the meanings of the word “narrative”, we find the fiction behind the fact.

Some words are so big that they become meaningless.

Let’s put that more precisely: Some terms are used so generally that their denotations are harder to pinpoint than people who use or people who hear such words may realize. Try to define exactly what “freedom” means, or “democracy”.

Out of the field that concerns us here, at least two terms have reached this general ‘buzzword’ status: “storytelling” and “narrative”.

There are professions and there are fields of study trying to get to grips with storytelling and narrative, for instance the profession of dramaturg or the theoretical approaches of narratology.

- Dramaturgy is defined as the craft, art, or the practice and techniques of dramatic composition or theatrical representation, where composition refers to the way in which the various parts are put together and arranged. In other words, structure.

- Narratology is defined as the study of structure in narratives or the study of narrative and narrative structure, where a narrative is something that is narrated, a representation or description of an event or series of events with the connections between them – that is, of a story.

Especially in American English, there is a second meaning to the word narrative, one that hasn’t made it into the British Collins dictionary yet and only to 2c in the OED, though by now the term is used widely in UK media in the same way as in the States and the rest of the world: “A way of presenting or understanding a situation or series of events that reflects and promotes a particular point of view or set of values“ (Merriam-Webster). In other words, ideology.

In this second definition, the term “point of view” is used generally, not in the technical or dramaturgical sense that a cameraperson or a novelist would use when talking about a scene. In the same way that PoV is a far narrower technical term within storytelling than in general use, so is “narrative” far broader in general use than among authors talking shop. Hence for technical use, we need yet another definition, one that is much more precise than what you find in a general dictionary: (more…)

Dramaturgical techniques in news stories.

This post is adapted from a longer piece by one of our founders on his personal Substack. Read the full article here (just click “no thanks” if you don’t want to subscribe).

If we’re watching a movie or reading a novel, we want a good story that reaches us on an emotional level. We demand to be excited, moved, aroused, even outraged or scared witless.

People enjoy the emotions that stories provoke. Emotional responses are the reason we succumb to stories, and storytellers deliberately try to elicit the “visceral” effect that powerful feelings engender. In order to root for the heroine, she must be placed in danger; in order to empathise with the hero, the audience must be able to identify with him and care about his fate. Writers and storytellers do a lot to engage the audience and keep them reading or viewing. The best techniques to maintain the audience’ attention are the ones that grab the audience emotionally. Stir them! Excite them! Make them feel! Boredom sets in when there is no increased heart rate, no sweaty palms, no rapt attention.

“Our top story tonight: …”

Newspapers and other news media such as television or online news portals know as well as novelists and moviemakers that the promise of emotion is what gets the audience’ attention in the first place and the delivery of emotion is what maintains it. Hence news media employ some similar techniques to fiction authors and screenwriters. Not for nothing is a news show or paper divided into “stories”. (more…)

When the bad guy makes the hero’s journey difficult.

Let’s say your hero or heroine is a falsely accused fugitive from the law. While on the run, every policeman or government agent is effectively an antagonistic obstacle. This is particularly the case if there is a specific character who represents the state and whose mission it is to catch the heroine. This detective or agent casts out the net to catch the fugitive, using all the instruments of the state at his or her disposal in order to actively thwart the heroine’s escape.

Or maybe your story is about a soldier behind enemy lines on a mission to find and destroy (or steal) the enemy’s new super weapon, or perhaps rescue an important person who has been captured. Any enemy soldiers the hero encounters are, of course, obstacles. One could say that they are external obstacles if they just happen to be there, like a patrol unit. But if there is on the enemy side a character who is aware of our hero’s approach and is actively seeking to stop him achieving his mission, then the soldiers and/or henchmen this character sends out to find the hero are not external obstacles but antagonistic obstacles.

As we have said before, this division into three classes of obstacles – internal, external, and antagonistic – is not cut and dried and need not be followed too strictly. But differentiating between the different kinds of obstacles a hero or heroine must face while designing and planning your story can lead to a more exciting plot, simply because you can disperse the obstacles systematically within the story journey and have all the different kinds of obstacle build up to a great crescendo at the climax. (more…)

Some Points to Ponder.

Should we reassess the success of our storytelling?

The Evolution of Stories

In previous posts we described the evolutionary case for storytelling. There is a point to telling stories, a reason why we do it. Stories have a deep “biological” function. The idea is that the fact that we as a species tell each other stories is an evolutionary adaptation which has increased our ability to survive and thrive on this planet.

And while the argument seems very plausible to us, the description of humans as “the storytelling animal” also seems to us to indicate the typical hubris of our species. By calling ourselves that, we set ourselves apart from the other animals who share our planet, who ostensibly are not intelligent or gifted enough to be endowed with an instinct for narrative.

But who is to say that whales, wolves, or even bees don’t tell each other stories?

If an elephant never forgets, surely their memories are filled with events and occurrences? And who is to say there are no plots and characters in these reminiscences, no themes or motifs in those recollections, no dramaturgy to those pachiderm pasts? (more…)

Long or short form, commercial or artistic: stories need to be developed before they are told.

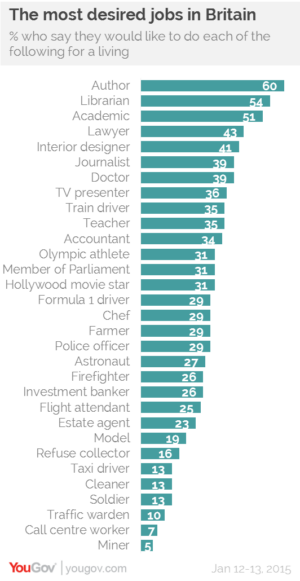

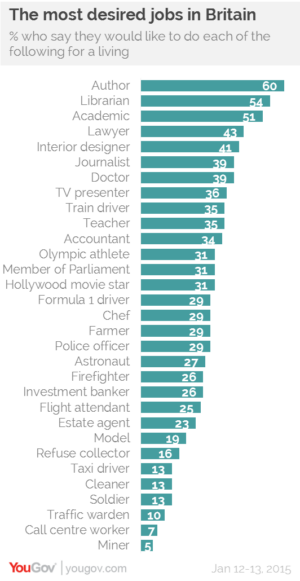

The fewest of people with the inclination to write stories actually make a living off it. There are more unsuccessful authors and screenwriters than successful ones, if we measure success in terms of monetary remuneration. And there are yet more people who would love to write that book but never seem to get around to it.

In fact, according to a 2015 YouGov poll in the UK, being an author is the most desirable job in that country. 60% of Britons want to write for a living! In the land of the Bard, J.K. Rowling, and Richard & Judy, perhaps that is not so surprising. Yet we may assume that in other countries too, the desire to tell stories is quite prevalent.

Practice makes perfect, so they say. The best way for a writer to improve their writing is to write. You may have heard of the theory that to be really, really good at something, you need to have done 10,000 hours of it.

But who has 10,000 hours to spare before producing anything readable?

We would contend that any writing is practice. The artist in the garret must eat and so a suitable option would be earning from writing. This is, after all, an age in which content is regent. Perhaps it is even true that more stories are being told today than ever before. There is an abundance of media and channels, and all must be filled with material. Hundreds of original series are being produced for the streaming services, cinema is not dead after all, and neither is TV, publishers are still publishing novels while self-publishers do it too.

Advertising is another field in which storytellers can hone their craft. Every company needs its image video, every product its presentation. Even towns, nonprofits, and unions tell stories. (more…)

A story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. How to avoid the ‘saggy middle’.

The middle bit of a story is really the story proper. It is usually the longest section. It comes after the introduction of the main character(s) and the setting up of the context, that is the world of the story, as well as the problems and themes the story deals with.

At the end of the first section – prior to what we’re here calling ‘the middle bit’ –, the protagonist has decided to set off on the story journey. Obviously, this does not have to be physical journey through a particular geography, but it does mean that the main character is somehow entering into new and unfamiliar terrain. In this sense, every story is a ‘fish out of water’ story. The heroine must leave the comfort zone in order for the audience to feel interest in her plight.

Some authors jump right into this unfamiliar territory, showing the run up to it in flashbacks. Anita Brookner’s heroine Edith Hope has already arrived in the Hotel du Lac in the first sentence of the novel. Gradually the reasons for her stay here are revealed as the reader progresses through the novel.

Nonetheless, for an author, it may be advisable to create a marked threshold where the protagonist enters into the alien territory of the middle bit. The exploration and transversal of this territory is what on a plot level the middle bit is about, and it takes up the greater part of the story journey. (more…)

Creation Takes Time.

This is an age of faster, faster, more, more. At the latest since the advent of the internet, everything seems to be speeding up. Processes that took weeks a few decades ago now take only a few hours, things that in the twentieth century took hours now take place within minutes or seconds. You can get from A to B in less time than ever. The requirements on most of us for most of our work call for ever greater efficiency. We must not waste time. We must be quick.

Composing a story is a painstaking process. And yes, here at Beemgee we built our fiction tool in order to make the process of composing a story more efficient. We want to make it easier to organise a plot and determine the characters’ motivations – for the authors themselves, and for all the people communicating about the story, so between interested parties such as authors and their editors or screenwriters and producers.

But though we might want our authors’ efficiency to increase, let’s not kid ourselves. Composing a story is still a painstaking process. Because most of the time is spent thinking.

Thinking takes time. And that is mostly what plotting and outlining a story really is, thinking. (more…)

The midpoint is structurally the most significant point in a narrative.

Given that stories have a tendency to symmetry, the centre of a narrative should mark the zenith of the story arc, and with that, the pivotal point of the story.

So, to get to (mid)point: What happens in the middle of a story?

Here are some typical midpoint events:

- Something searched for is found (Star Wars IV, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lolita)

- A hidden truth is unveiled (to the audience, at least) – if not yet understood (Matrix, Pride and Prejudice, The Gruffalo)

- A dramatic event thwarts all plans made hitherto (James Cameron’s Titanic)

The centre of the narrative may be the discovery of something missing – in crime stories a vital piece of the puzzle may be revealed here (either to the audience or to the audience as well as the protagonist).

In any genre or dramatic category, the midpoint may be a moment of truth. This might be just a clue for the audience or perhaps an initial revelation of the true state of things.

If a character realises or finds out something that has so far been hidden, then this is the point at which the character begins to gain awareness. This counts in particular for the recognition of the character’s own internal problem. From here on the story might possibly lead up to a moment of choice at the crisis, when it becomes clear to the audience whether the character has learnt from this new awareness or not. In other words, the real need begins to overcome or supplant the character’s initial want due to what happens at the midpoint.

Some well-known examples of the midpoint

(more…)

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Today’s guest post is by author Stefan Emunds.

Stefan’s favorite genre is visionary fiction – stories that have an enlightenment dimension. Enlightenment and storytelling have interesting parallels, which prompted Stefan to write a book about storytelling – The Eight Crafts of Writing.

Get a glimpse of his approach to story craft in his article.

Art and Craft

Storytelling is both art and craft, authoring and writing, plotting and pantsing.

1.1 Art and Authoring

Art is creativity. Creativity requires receptivity to the Muse and its inspirations.

Inspirations arrive as thought-images, which writers put into words. How to turn thought-images into words and assemble those into a structured story with vivid characters and an engrossing world is a matter of craft and skill.

1.2 Craft and Writing

The literal meaning of Kung Fu is a discipline achieved through hard work and persistent practice. Writing is Kung Fu.

Craft gives form to inspirations. Forms limit. Writers love the artistic side of writing, less so crafting, in particular, Story Outline. Writers are prone to procrastinate crafting.

But no limitations, no story. No canvas, no painting. No net, no tennis.

Understanding the difference between freedom and dominion helps to appreciate the constraints of craft. Freedom is a means to an end. We want to be free to do something, for example, to write a book. That’s all there is to freedom. Dominion, on the other hand, is mastery of structure. (more…)

Here is a selection of books on the craft of storytelling, most of which we can recommend to budding authors.

Aristotle, Poetics. Oxford University Press, 2013. – Influential in the west, though to be read and interpreted with some caution.

Baxter, Charles, Burning Down The House. Greywolf Press, 2008. – Interesting essays on storytelling.

Beinhart, Larry, How To Write A Mystery, Ballantine, 1996. – Contains much that is true beyond genre writing.

Booker, Christopher, The Seven Basic Plots. Continuum, 2005. – More erudite than the title would suggest, and somewhat controversial since he favours classics and disses almost every story of the last 200 years.

Boyd, Brian, On The Origins Of Stories. Harvard University, 2009. – The world’s foremost Nabokov expert with a brilliant and comprehensive – though occasionally quite dry – explanation of why stories are an integral part of the human species, an evolutionary adaptation we couldn’t live without. (more…)

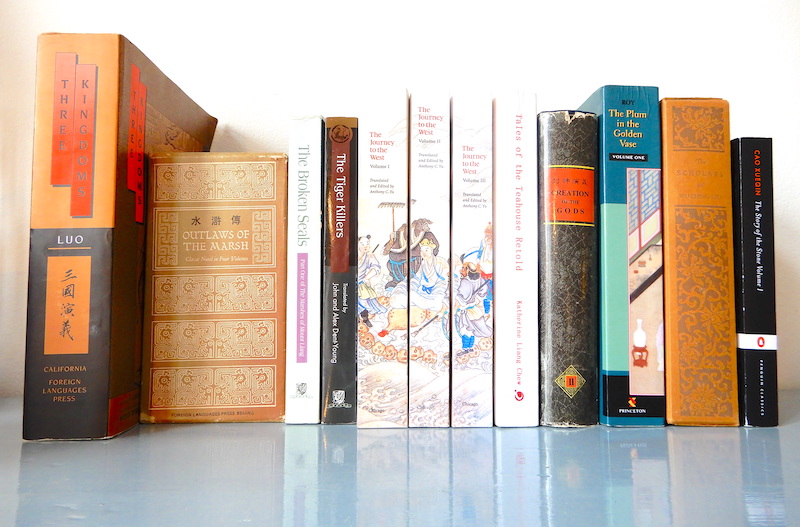

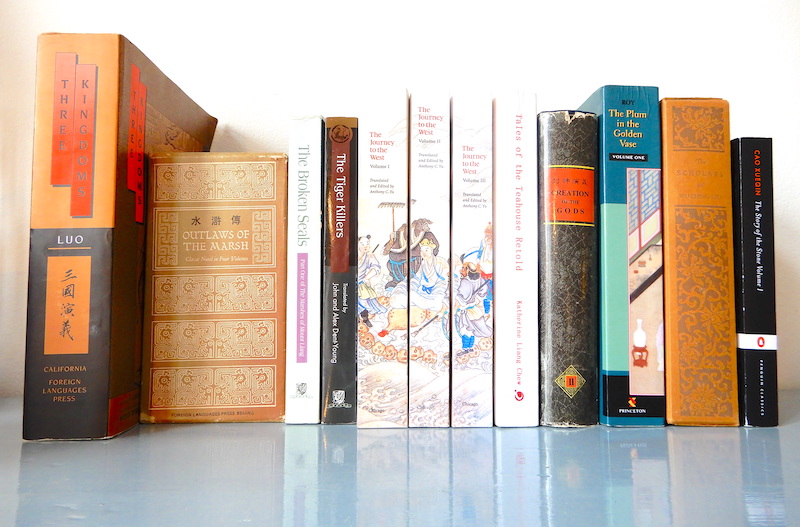

Take a look at your book shelf. Chances are there are European and North American authors there. Perhaps you have some Central or South American writers too. And maybe some Indian or Pakistani novels. And perhaps some Russians.

All of these authors wrote or write in the tradition of European storytelling, via colonial or cultural influence. Modern African authors writing novels, for example, have adopted this written prose text form although African storytelling traditions are primarily oral.

What most of us, at least in the western world, know about how to tell stories is influenced heavily by Aristotle’s Poetics. In this rather thin book, Aristotle describes some basic precepts of dramatic composition that continue to be circulated in creative writing classes and how-to books today.

Another strong influence on western storytelling is the protagonist/antagonist duality which arose along with Christianity. Would there be a Sauron without Satan? A Darth without the Devil? A Voldemort without Lucifer?

So what about stories that were created without any knowledge of Aristotle or Christianity? How are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different?

Let’s find out by asking … (more…)

Nothing should be more important to an author than how their story makes the audience feel.

As an author, consider carefully the emotional journey of the reader or viewer as they progress through your narrative.

The audience experiences a sequence of emotions when engaged in a narrative. So narrative structure is a vital aspect of storytelling. The story should be touching the audience emotionally during every scene. Furthermore, each new scene should evoke a new feeling in order to remain fresh and surprising.

The author’s job is to make the audience feel empathy with the characters quickly, so that an emotional response to the characters’ situation is possible. Only this can lead to physical reactions like accelerated heartbeat when the story gets exciting. We have to care.

This “capturing” of the audience, making the reader or viewer rapt and enthralled, requires authors to create events that will show who the characters are and how they react to the problems they must face. The audience is more likely to feel with the characters as the plot unfolds when the characters’ reactions to events reveal something about who they really are – and how they might be similar to us.

One Journey to Spellbind Them All

Here we present a loose pattern that we think probably fits for any type of story, whatever genre or medium, however “literary” or “commercial”. It’s not prescriptive, just a rough checklist of the stages in the emotional journey the audience tacitly expects when they let themselves in on a story. The emotions are in more or less the order they might be evoked by any narrative.

Curiosity

(more…)

Guest Post by KT Mehra.

KT Mehra knows a thing or two about writing from her own experience, not only as an author but as a supplier to writers and authors of fine stationary, in particular fountain pens. Not only that, she is digital savvy too.

Back in 1999, KT and her husband Sal started a small web company to create websites for local businesses and provide internet access. They both had a passion for fountain pens, and one day KT, in an excess of enthusiasm, ordered far too many from a pen company. Just for fun, she decided not to return any of them and instead asked her team to design an e-commerce website to sell the extra pens.

To everyone’s surprise and just like that, the website came together quickly and was an instant success.

KT believes that in the modern digitally saturated world, it’s more important than ever to stay true to your thoughts and create something tangible. In that spirit of creation, she feels that something as elemental as putting pen to paper is ever more essential.

Despite offering a digital tool for authors, we couldn’t agree more!

Develop a romantic relationship that your readers will engage with and root for.

Most of the romance novels you love so much use certain secrets to hook their readers in and keep them engaged.

Learning the secrets to create such compelling romance novels will help you perfect your characters’ love story.

The Basics

The best way for your readers to relate and root for your relationship is for you to make it realistic and dynamic. To build the foundation of any great love story, you need to have a few things down first. (more…)

Guest post by Rachael Cooper.

Rachael Cooper is the Publishing Manager for Jericho Writers, a writers services company based in the UK and US. Rachael has a Masters in eighteenth-century literature, and specialises in female sociability. In her free time, she writes articles on her favourite eighteenth-century authors and, if all else fails, you can generally find her reading and drinking tea!

What is a manly novel, or a womanly novel for that matter?

Does it matter that 1984 was written by a man, or that a woman penned Harry Potter?

Like anything, people lump writers into stereotypes and groups, along with their work. In some ways, this makes it easier to categorize and begin understanding their novels. In others, it can handcuff an audience’s reading and pigeonhole writers.

Women have been writing, and out writing, men for millennia. From Sappho to Toni Morrison, Jane Austen to Virginia Woolf, myriad women writers have changed the world with their words.

Out of all the novels written by women, these are three of the most “manly” of all, the ones you’d bet were written by men.

(more…)

(more…)

The essential elements of a story.

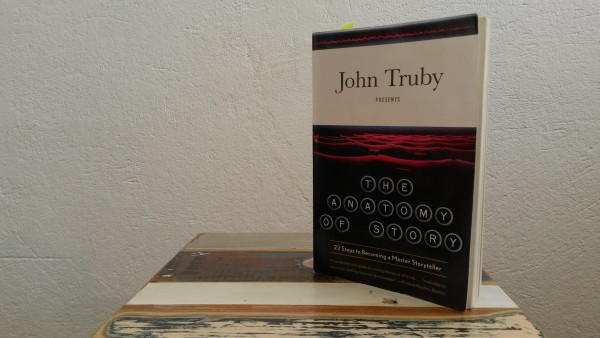

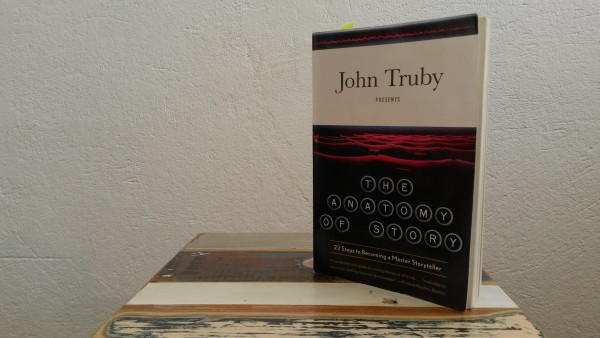

One of the many experts on storytelling to have attempted in a book to describe the essential elements of a story is John Truby.

In The Anatomy of Story (2007), Truby identifies 22 steps in any protagonist’s narrative, which may play into four aspects of the story: character, plot, story world, and moral argument. Thankfully, Truby does not insist that every story must follow the template strictly and contain all 22 steps. He does, however, identify as critical that the story show seven attributes of a main character and their storyline: (more…)

You might think that your story could be enjoyed by anyone. But most stories particularly appeal to more or less specific target groups.

When you’re developing a story, it helps to have an idea of kind of people who are going to be enjoying it. The more specific this idea, the more likely you are to conceive and form the material in a way that will appeal to them.

The Ideal Audience

So while you are writing a story, you may have an ideal reader or viewer in mind. This might be your projection of a particular real individual, or just a vague idea of a type of person. Your ideal reader or viewer gets every joke, spots every reference – no matter how obscure –, and feels just the way they should during each scene.

The ideal audience is a figment of the author’s imagination. Picturing this figment in as much detail as possible in your mind’s eye might be a good starting point for finding out who your target audience is. Is the ideal reader a gentleman sitting in an armchair? Or a teenage girl lounging in a café?

Specifying your target audience to industry professionals you’re pitching to can make it easier for them to judge whether your work is something they can invest in. Typically, the criteria for target groups are: (more…)

Dramaturgy means “the craft or the techniques of dramatic composition”.

In other words, everything to do with the story except the words with which it is told. If your story is about two people in a room, dramaturgy tells you who these people are and what happens in the room. In terms of storytelling process, the term dramaturgy refers to the planning or outlining stage rather than the execution or writing.

The study of dramaturgy has produced a nomenclature that is used by dramaturges, script consultants, story advisors, editors and publishers, producers and filmmakers, as well as authors. Some terms may seem more familiar than others, and often their definitions are not entirely agreed upon. (more…)

Guest post by Hayley Zelda.

Hayley Zelda is a writer and marketer at heart. She’s written on all the major writing platforms and worked with a number of self-published authors on marketing books to the YA audience. She loves working with teen writers and working with schools on literacy programs.

Writing is a craft that cannot be easily taught and from a young age, many students associate writing with homework and essays. By the time high school swings around, many teachers tell me they’ve given up on getting the majority of students excited about writing.

But I believe there is always a way to motivate and inspire young minds to get excited about writing. After all, storytelling has been in existence since the beginning of the human race. And who doesn’t love stories?

If it were a simple task, I probably wouldn’t be writing a blog post about it. Through trial and error, I’ve found a number of ways to help teens have fun while writing. This doesn’t mean that every teen will fall in love with writing forever, but at least some positive association can be built with the act of writing.

Here are some of my top tips on how to get young people excited about writing.

1. Use writing prompts relevant to what young people care about.

Writing prompts are a great way to get creative juices flowing. The more relevant you make the prompt, the stronger the response you’ll get from a student. (more…)

If you dont know what your story is really about, start finding out now (and don’t stop).

By Amos Ponger

Mankind’s Stories

The human ability of creating stories and the consumption and absorption of stories are very deeply connected to the core of our civilizations. Our efficiency as a species and cooperation in all scales of human endeavor rely on our ability to tell, decode, understand, and believe in stories.

Story has been so important for mankind’s cooperation, development and the way humans have understood themselves that all of our grand evolutions and revolutions – from the agricultural, religious, economic and cultural revolutions, the invention of money and law, the renaissance and humanism, the American, French and Russian revolutions, modernism, to socialism and capitalism – have actually happened through processes of rewriting collective Story. Revolutionaries and evolutionaries from Moses through Jesus, to Buddha, have actually risen upon a grand scale transformation of how humans understand themselves and cooperate with each other. And that has been done by story. Often the seeds of politics of whole centuries had actually been sown by poets, philosophers and prophets. STORYTELLERS.

Your Story

Now, even if you don’t plan on a revolution(more…)

Six Suggestions to Beat the Block.

By Silvia Li Sam

By Silvia Li Sam

Silvia Li Sam is a storyteller, blogger, writer, and marketing expert. She has built communities of millions of people in education, tech, and non-profit. You can see some of her storytelling credentials on Medium at silvialisam.com, or connect with her on her LinkedIn.

What’s worse for an aspiring writer than to sit in front of their laptop with every intention of writing a great story, only to discover you can’t think of a single idea?

Don’t worry: we’ve all been there. All you need is a dash of inspiration, and you’ll be penning that story – or that novel! – in no time.

But how can you brainstorm great ideas? In this article, we’ll give you a few tips to battle writer’s block and never lose to it again!

1. Write down everything that comes to mind!

You might be asking yourself, “What am I supposed to write about? I don’t have any ideas!”

Don’t worry, the objective here isn’t writing anything exceptional, it’s just getting rid of the white page sitting in front of you. So type into your computer (or write down if you still use a pen and papers) anything you can think of. (more…)

In recent years, scientists have been writing books about the reasons why we tell each other stories.

Neurobiologists have discovered that when a person is immersed in a story, their brain patterns are similar to what they would be if that person were actually performing the actions they are reading about or watching. So if a recipient is emotionally engaged in a story, they are essentially “living” it – at least in terms of the brain patterns. The excitement is real, the fear, the empathy, the arousal. See Boyd, 2009, or Gottschall, 2012*.

Simulation

This has given rise to the analogy of the flight simulator.

Stories are everywhere. We create and consume them from an early age. Homo sapiens have done so for millennia – our modern media are a result of our ancient need for stories. We have been telling them to each other ever since we, as a species, have been human. It’s what homo sapiens do. It’s a defining characteristic. What evolutionary biologists call an “adaptation”.

That means there is a reason for us to tell stories: They help us survive. (more…)

Virtual Reality technology (VR) has fascinating effects on storytelling.

Photo by NeONBRAND on Unsplash

The VR viewer wears special goggles and occupies a space within a virtual holodeck, which is created by two diagonally opposing little boxes shooting lasers out at right angles. The viewer can move within this virtual space, which might be the stage for a story. The goggles will show the viewer whatever program is loaded, Matrix-like. The 360° view is created quite conventionally, by filming a location in all directions, the camera at the centre, pointing outwards and panning all the way round.

So far, so good. It gets more interesting when such virtual locations are populated.

For VR, actors are filmed not with one or two cameras from a couple of angles, but with 40 or more cameras from all angles, the cameras all pointing inwards with the actor at the centre. The resulting 40 or more images are stitched together. The VR goggle wearer can therefore walk around the actors and see them from the front, from behind, from any angle. The actor was never at the location, but is superimposed into the virtual space (this already happens in conventional film with green screen technology).

What you get is the viewer as a ghost, moving about the story stage and around the characters at will. The effect is like intimate theatre. (more…)

by Amos Ponger

A pledge to transformational storytelling

Working for over 20 years as an award winning film editor and story consultant, Amos Ponger studied film science, cultural sciences, art history and multidisciplinary art sciences at The FU Berlin, Humboldt University Berlin and the Tel Aviv University. He has a Master’s degree from the Steve Tisch School of Film in the Tel Aviv University, worked as an editing teacher in two Israeli film academies, is senior advisor to our story development tool Beemgee.com, and recently co-founded the story consulting service Mrs Wulf. Book his services directly here.

The Transformational Process of Creating a Great Story

We all know that creating a great story is a process that can sometimes take many months and even years to fulfill.

If you talk to professional writers they will probably tell you that they have complex relationships with these processes of writing. Involving dilemmas, fear and joy, suffering and excitement. And that these self-reflexive processes are also processes of self-exploration.

Yet many writers, scriptwriters, filmmakers tend to put a lot of energy into their external journey towards completing their story, focusing on drama, act structure, “cliff hanging”, while neglecting minding their own internal processes on their journey.

What many film and story editors encounter while working with directors and writers is that authors and directors tend to have a very strong drive. They endure months in writing solitude, or filming in deserts, storms, war zones, perhaps even putting themselves in danger in order to realize their artistic vision. Yet at the same time very often they have a remarkable incapability of explaining WHY they HAVE to do it, and can only do so in very vague terms. (more…)

How narrative structure turns a story into an emotional experience.

Image: Comfreak, Pixabay

Storytelling is a bit of an overused buzzword. While we are all – by dint of being human – storytellers, how aware are you of the principles of dramaturgy? What exactly constitutes a story, in comparison to, say, a report or an anecdote?

And just to be clear, the following is not a story. It’s an how-to article.

Whatever the medium – film or text, online or offline –, storytelling has something to do with emotionally engaging an audience, that much seems clear. So is a picture of a cute puppy a story? Hardly.

Stories exist in order to create a difference in their audience. Stories always address problems and tend to convey the benefits of co-operative behaviour.

While there simply is no blueprint to how stories work, let’s examine the elements that recur in stories and try to find some patterns.

Who is the story about?

All stories are about someone. That someone does not have to be a person, it can be an animal (Bambi) or a robot (Wall-e). But a story needs a character. In fact, all stories have more than one character, with virtually no exceptions. This is because the interaction between several characters provides motivation, conflict and action.

Moreover, stories usually have a main character, the figure that the story seems to be principally about – the protagonist. It is not always obvious why one character is the protagonist rather than another. Is she simply the most heroic? Is she the one that develops most? Or does she just have the most scenes?(more…)

Antje Tresp-Welte is the winner of the Your Perfect Plot challenge set by BoD and Beemgee.

In her guest blog post, she gives frank insight into her writing process and her experiences with Beemgee.

Short stories were child’s play

Short stories were child’s play

When something intrigues me, I spin a story out of it. Until a few years ago I wrote mostly fairy tales, short stories for adults, poetry and stories for younger children, some of which were published in magazines. My story about a bad-tempered spectacled snake was published as a little book, “Charlotte and the Blue Lurker”. For all these stories I only sketched a few thoughts as planning and then wrote them down relatively quickly.

By now, book projects fascinate me too. Currently they are crime novels and fantasy for children from 8 or 10 years.

Long takes longer …

During a holiday at the North Sea I had the idea for my first crime novel. In it, the protagonist, an eleven-year-old very imaginative boy with a penchant for drawing, not only saves his grandma’s tea room from demolition, but is also involved in a mysterious story about a pirate who died long ago. I developed the original idea into a plot at a seminar for authors. I found the topic so great that I couldn’t wait to start writing it. Beforehand, I made notes on the individual characters and considered important cornerstones of the plot with the help of the hero’s journey. I started off with a great momentum and was soon able to read the first chapters to my son. Unfortunately his comment was, “Mama, that is much too long!”

… not to be longwinded

My two test readers came to a similar conclusion and I too had noticed that it somehow “grated”. I wasn’t really getting to the point. Was it due to my preliminary planning? Was it not detailed enough? I dived into the text, shortened passages, removed individual characters and worked out others more precisely. This changed entire storylines. At the same time my story gained more (narrative) speed and I found the tone for the language. (more…)

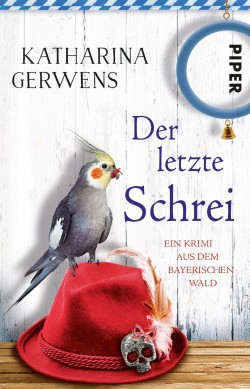

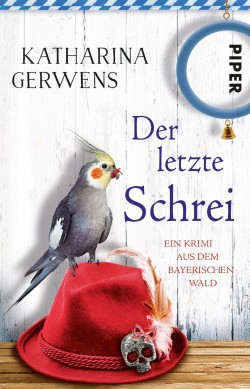

The first novel to state in black and white that the author worked with Beemgee.

This is certainly not the first book for which our author tool was used. But it is the first time that an author explicitly mentions Beemgee in her acknowledgements. Thank you, Katharina, we’re glad you use Beemgee during your story development!

All The Rage – Der letzte Schrei

All The Rage – Der letzte Schrei

published by the renowned Piper Verlag (Bonnier group)

Susanne Pfeiffer has recently joined the Beemgee team. She interviewed her friend Katharina Gerwens for us.

Beemgee: Congratulations, Katharina! It’s always great when you can hold your own book in your hands … How many novels have you published so far?

Katharina: This is my eleventh regional thriller published by Piper. Soon I’ll make it a dozen ….

Beemgee: I think ALL THE RAGE is a really good thriller title! You like double meanings. – But I want to get at something completely different: You know my foible to start every book by reading the acknowledgements – and here it says, last but not least, you worked on the plot with BEEMGEE! How so?

Katharina: Because for me any support I get is worth mentioning! I have asked so many people in my field about all sorts of things, and in these conversations new aspects have always emerged – the least I can so is say thank you! ALL THE RAGE is, by the way, the first book in which I worked with Beemgee – and it was a great help to me. (more…)

Reflections on dialectically guided writing, or: Can dialectics help us tell better stories?

Guest post by Richard Sorg.

Guest post by Richard Sorg.

Prof. Dr. phil. Richard Sorg, born in 1940, is an expert in dialectics. What is that, and what does it have to do with my novel? Well, “All great, moving and convincing stories are inconceivable without the central significance of the contradictions and conflicts that represent the driving energy of movement and development.” This puts us in the middle of dialectics. And of storytelling.

After studying theology, sociology, political science and philosophy in Tübingen, West Berlin, Zurich and Marburg, Richard Sorg taught sociology in Wiesbaden and Hamburg. His book “Dialectical Thinking” was recently published by PapyRossa Verlag. (Photo: Torsten Kollmer)

Ideas that contain a potential for conflict.

Sometimes there is a single but central chord at the beginning of a piece of music, even an entire opera, which is then gradually unfolded. Its inherent aspects, harmonies and dissonances emerge from the chosen, sometimes inconspicuous beginning, undergoing a dramatic, conflictual development, so that a whole, complex story emerges at the end of the path of this simple chord after its unfolding. This is the case, for example, with the so-called Tristan chord at the beginning of Richard Wagner’s opera “Tristan und Isolde”, a leitmotif chord that ends with an irritating dissonance.

The beginning of a story is sometimes an idea, an idea which you may not know how to develop. But some such ideas or beginnings carry a potential within them that is capable of unfolding and which holds unimagined development possibilities. ‘Candidates’ for viable beginnings – comparable to the dissonant Tristan chord mentioned above – are those that contain a potential for conflict or contradiction within. But it can also be a calm with which the matter is opened up, a calm that may then prove to be deceptive. We also find something similar in some dramas, for example with Bertolt Brecht.

And with that, we are already in the middle of dialectics. (more…)

What do we mean when we talk about story structure?

A story is a complex entity comprising many interrelating parts. The author imposes some sort of organising principle onto the material, turning the story into a narrative. The result of this forming or shaping of the material is the story structure.

Certain structural markers are so explicit that the audience is aware of them, such as chapters in novels. Elizabethan plays are typically divided into five acts. A film script is broken down into acts, sequences, and scenes.

The beat is the smallest unit of story, below the scene in the structural hierarchy. It is the space between an action and the reaction it causes within a scene.

- Beat

- Scene

- Sequence

- Act

- Story

A plot event is not part of this traditional hierarchy, being more of a meta-unit somewhere between beat and scene.

Scenes and acts are defined in screenplays, like chapters in novels. But stories have structures that are not usually made obvious or explicit.

Beats

There are two different understandings of the term beat.

A scene may be broken down into beats – marked only by the moments when the mood or relationship the scene describes changes. Two characters are having a conversation, character A says something which makes character B react in a different way from what A expected – that’s a beat.

The term beat is also sometimes used when marking such changes on a bigger scale, across an entire narrative. Some screenwriters work with so-called beat sheets; in the Beemgee outlining tool, the plot event cards are perfect for creating beat sheets, since each card is designed to stand for one plot event. In a beat sheet, a beat is one unit of plot. If you think of narrative as a chain of events, then each beat is a single link. In one school of thought, a Hollywood movie is ideally constructed of exactly 40 such beats. (more…)

UPDATE: The winner is … Call for story outlines by Beemgee, Ink-it and CONTEC México 2017.

This is Yolanda Prieto Pardo, whose story outline LOS ALTOS VUELOS DE JOSEFINA was chosen in the Fiction without Friction contest we ran with Contec México and Ink it. She has won a lifetime subscription to Beemgee Premium. Furthermore, our friends at Ink it will publish the novel online all over the world in 85 countries.

Congratulations Yolanda!

The CONTEC/Beemgee “Fiction without Friction” call for stories

Many innovations relevant to authors of stories and “content” apply to publication and distribution. However, digital aids can also help creators right from the moment they have their first ideas.

With Beemgee.com, fiction authors have a tool that helps them organize their plots and develop their characters. When it comes to pitching the work to a publisher, a Beemgee project provides a powerful supplement to the traditional exposé.

For publishers and other content disseminating organizations, Beemgee is a new tool that increases productivity during the evaluation process and considerably improves the workflow between author and editor/producer/publisher.

To showcase this new approach, CONTEC and Beemgee are running a call for stories, which the ebook platform ink-it is supporting.

Turn your story into a book for sale in over 40 online stores! (more…)

Author and creative writing teacher Jesse Falzoi was born in Hamburg and raised in Lübeck, Germany. Back in the nineties, after stays in the USA and France, she moved to Berlin, where she still lives with her three children.

She has translated Donald Barthelme stories into German. Her own stories have appeared in American, Russian, Indian, German, Swiss, Irish, British and Canadian magazines and anthologies. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Sierra Nevada College.

Her new book on Creative Writing is released end of May 2017.

At the age of twenty-one I quit university and bought a one-way ticket to San Francisco, USA. I wanted to get far away from my first attempts to grow up. I wanted to get away from a frustrating relationship and boring courses and everything that was pushing me to take life more seriously. I didn’t have any plans what I would be doing in San Francisco but I had the address of an acquaintance I had made a year before. I went on a journey that was physical in the beginning and became more and more spiritual during the process. I bought a return ticket in the end and went back to my hometown just to pack my suitcases for good; I’d be staying in Germany, but I wouldn’t be staying home.

(more…)

Conflict is the Lifeblood of Story.

In real life, conflict is something we generally want to avoid. Stories, on the other hand, require conflict. This discrepancy is an indicator of the underlying purpose of stories as a kind of training ground, a place where we learn to deal with conflict without having to suffer real-life consequences.

In this post we will look at:

- An Analogy

- Archetypal conflict in stories

- Conflict between characters

- Conflict within a character

- The central conflict

Along with language (in some form or other, be it as text or as the language of a medium, such as film) and meaning (intended by the author or understood by the recipient), characters and plot form the constituent parts of story. It is impossible to create a story that does not include these four components – even if the characters are one-dimensional and the plot has no structure. However, it is formally possible to compose a story with no conflict.

It just won’t be very interesting.

In terms of narrative, conflict is presented as a series of confrontations of increasing intensity. If there are no confrontations – no battles of wits or fists, no crossing of swords or sparring with words – there is little to hold the audience’ attention. To create confrontations, there must be at least a of conflict of interest between the characters.

Conflict does not occur at particular points in a story. It permeates the whole of it. It expresses the values transported by the story’s theme. It creates at least two options of choice, both of which must appear to some extent reasonable and justifiable to the protagonist, particularly at the moment of crisis.

(more…)

The term motif refers to any recurring element – in storytelling as in music or other arts.

Examples of elements that turn up repeatedly within a whole are an image on a tapestry or a particular sequence of notes in a symphony. The dispersal of these elements creates a pattern. It is therefore part of the artist’s craft to have some sort of design principle determine this pattern.

What motifs do

Motifs do not make a plot. But since they make patterns they are part of the structure of a story. And they help add a layer of meaning.

In other words, if a motif is present excessively in the first half of a story, and hardly at all in the second, then the author had better be aware of a reason for this uneven distribution. The distribution – the pattern – carries meaning to the audience. Remember, the audience yearns for meaning, is always striving to understand what the story is trying to convey at any given point. This demand for some sort of raison d’être for each element of a story, or for a sense of order within the whole, may well be unconscious to the audience much of the time, but ultimately the experience of the story is more satisfying when the audience can work out reasons and meaning.

In stories, motifs can be almost anything. Objects, actions, metaphors, symbols, colours, or images can be motifs. What defines an element as a motif is the systematic deployment within the story rather than the thing itself.

How motifs work

Motifs work best when(more…)

Detectives and other investigators abound on our TV and cinema screens.

In the western world, crime fiction – mystery, thrillers, suspense, whodunnits, etc. – makes up somewhere between 25 and 40 percent of all fiction book sales. Why is the crime genre so popular?

Crime is fascinating, to be sure, because most of us don’t commit it. But the popularity of the genre has little to do with crime per se. It has far more to do with the very essence of how storytelling works.

In this article we will be looking at:

- Cause and Effect

- Agency

- The Whydunnit

- The Narrative Principle

- Why Some People Don’t Like Crime Stories

- The Search For Truth, or Gaining Awareness

- How Crime Is Like Comedy

Cause and Effect

Crime fiction exhibits most clearly one of the fundamental rules of storytelling: cause and effect. In crime fiction,(more…)

Archetypes in stories express patterns.

While plots may be “archetypal” when they exhibit certain forms, in this post we are concerned with character archetypes.

In modern storytelling, to consider them as archetypes might suggest a bit of a corset, perhaps even a straightjacket for the characters. For today’s author, to present a character as an archetype does not seem conducive to achieving psychological verisimilitude.

But an archetype is not the same as a stereotype. An advisor or mentor does not need to be a wise old man like Obi-Wan Kenobi. And an antagonist does not need to be a baddy.

Consider archetypes as powers within a story. Like planets in a solar system, they have gravity and they therefore exert force as they move.

Archetypes denote certain general roles or functions for characters within the system of the story. There is ample room for variation within each role or function. Boundaries between one archetype and another may be fuzzy. And it is possible for one character to stand for more than one archetype.

Archetypes Through The Ages

(more…)

It’s the way you tell it.

Narrative is the choice of which events to relate and in what order to relate them – so it is a representation or specific manifestation of the story, rather than the story itself. The easy way to remember the difference between story and narrative is to reshuffle the order of events. A new event order means you have a new narrative of the same story.

Narrative turns story into information, or better, into knowledge for the recipient (the audience or reader). Each story event is a unit of knowledge the audience requires.

A narrative is paradox, because it seeks to convey truth by hiding it. A storyteller arranges the items of knowledge in such a way that they are revealed gradually, which implies initially obscuring the truth behind what is told. Such deliberate authorial obfuscation creates a sense of mystery or tension, and creates a desire in the audience to find out what is happening in the story and why. In this sense, a narrative is effectively the opposite of an account or a report.

A report presents information in order to be understood by the audience immediately, as it is being related. A neutral, matter of fact presentation probably maintains a chronology of events. It explains a state of affairs blow by blow, and aims for maximum clarity at every stage. It seeks to convey truth by simply telling it. While the point of a narrative is also that the recipient perceives the truth of the story, in a narrative this truth is conveyed indirectly. Narrative is therefore responsible for how the recipient perceives the story.

In this article we’ll look at

- Story Basics

- The Components of Story

- Text Types That Describe A Story

- Author Choices: Genre and Point of View

- Causality in Narrative

Story Basics

First, let’s state some basics as we understand them here at Beemgee: a story consists of events that are related by a narrator; events consist of actions carried out by characters; characters are motivated, they have reasons for the things they do; there is conflict involved; one and the same story may be told in different ways, that is, have varying narratives.

Note that we are talking here about narrative in the dramaturgical sense – not in the social sense. Like the term “storytelling”, the word “narrative” has become a bit of a buzzword. We are not referring here to open “social narratives” such as “the American narrative”. For the definition and exploration of such collective narratives, see our article in The Bigger ‘Narratives’ of Society. Here, we are pinpointing the use of the term primarily for storytellers creating novels, films, plays, and the like. Such works tend in their archetypal form to be closed narratives with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

A narrative may present the events of the story in linear, that is to say chronological order or not. But the story remains the story – even if it is told backwards.(more…)

Today’s guest post is by writer Jason Brick. He has published his work in all sorts of genres and formats, with over 3000 articles, short stories, novels and non-fiction to his name – and about 20 books which are not, because he has ghost-written them. Jason also edits and crowdfunds anthologies. Next to writing, Jason loves martial arts and travel. We’re happy Jason has taken the time to explain flash fiction for us.

Today’s guest post is by writer Jason Brick. He has published his work in all sorts of genres and formats, with over 3000 articles, short stories, novels and non-fiction to his name – and about 20 books which are not, because he has ghost-written them. Jason also edits and crowdfunds anthologies. Next to writing, Jason loves martial arts and travel. We’re happy Jason has taken the time to explain flash fiction for us.

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.

Cris is a tech enthusiast who, next to writing, loves photos and videos. He likes technology, including video editing and programming. He provides guest content for different platforms and currently works for veed.

By Silvia Li Sam

By Silvia Li Sam

Guest post by Richard Sorg.

Guest post by Richard Sorg.