The stories we tell each other collectively – sorting out the meanings of the word “narrative”, we find the fiction behind the fact.

Some words are so big that they become meaningless.

Let’s put that more precisely: Some terms are used so generally that their denotations are harder to pinpoint than people who use or people who hear such words may realize. Try to define exactly what “freedom” means, or “democracy”.

Out of the field that concerns us here, at least two terms have reached this general ‘buzzword’ status: “storytelling” and “narrative”.

There are professions and there are fields of study trying to get to grips with storytelling and narrative, for instance the profession of dramaturg or the theoretical approaches of narratology.

- Dramaturgy is defined as the craft, art, or the practice and techniques of dramatic composition or theatrical representation, where composition refers to the way in which the various parts are put together and arranged. In other words, structure.

- Narratology is defined as the study of structure in narratives or the study of narrative and narrative structure, where a narrative is something that is narrated, a representation or description of an event or series of events with the connections between them – that is, of a story.

Especially in American English, there is a second meaning to the word narrative, one that hasn’t made it into the British Collins dictionary yet and only to 2c in the OED, though by now the term is used widely in UK media in the same way as in the States and the rest of the world: “A way of presenting or understanding a situation or series of events that reflects and promotes a particular point of view or set of values“ (Merriam-Webster). In other words, ideology.

In this second definition, the term “point of view” is used generally, not in the technical or dramaturgical sense that a cameraperson or a novelist would use when talking about a scene. In the same way that PoV is a far narrower technical term within storytelling than in general use, so is “narrative” far broader in general use than among authors talking shop. Hence for technical use, we need yet another definition, one that is much more precise than what you find in a general dictionary: (more…)

A story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. How to avoid the ‘saggy middle’.

The middle bit of a story is really the story proper. It is usually the longest section. It comes after the introduction of the main character(s) and the setting up of the context, that is the world of the story, as well as the problems and themes the story deals with.

At the end of the first section – prior to what we’re here calling ‘the middle bit’ –, the protagonist has decided to set off on the story journey. Obviously, this does not have to be physical journey through a particular geography, but it does mean that the main character is somehow entering into new and unfamiliar terrain. In this sense, every story is a ‘fish out of water’ story. The heroine must leave the comfort zone in order for the audience to feel interest in her plight.

Some authors jump right into this unfamiliar territory, showing the run up to it in flashbacks. Anita Brookner’s heroine Edith Hope has already arrived in the Hotel du Lac in the first sentence of the novel. Gradually the reasons for her stay here are revealed as the reader progresses through the novel.

Nonetheless, for an author, it may be advisable to create a marked threshold where the protagonist enters into the alien territory of the middle bit. The exploration and transversal of this territory is what on a plot level the middle bit is about, and it takes up the greater part of the story journey. (more…)

You have likely heard of The Divine Comedy, of Don Quixote, of Shakespeare – but have you heard of the Three Kingdoms? Of Sun Wukong? Of Cao Xueqin?

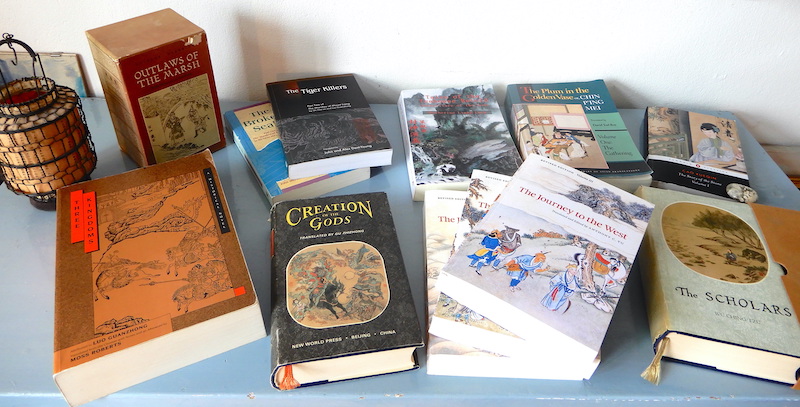

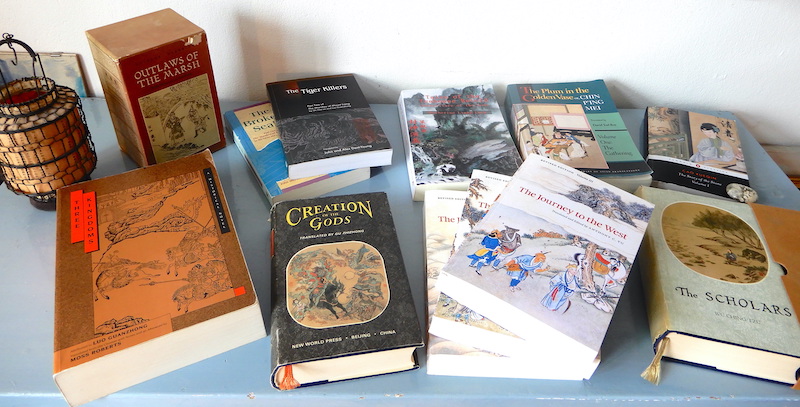

We asked ourselves, how are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different? Are the principles of storytelling really universal across cultures? Our idea was to find out by taking a look at classical Chinese literature. We discovered a number of interesting aspects to the Chinese way of telling stories, and have summarised them here.

In this post, we’ll tell you about the novels we read. Each was a revelation in its own way. The long-form novel came along quite suddenly in China just over 500 years ago. Generally recognised as the first great Chinese novel is Three Kingdoms, which appeared around 1494 CE. The most modern of the novels we’re considering here was published around 1760. That means we’re looking at Ming and Qing dynasty literature.

So which classical Chinese novels should you read? Here’s our list of favourites.

Our Top 7 Classical Chinese Novels

Nr 1

(more…)

The essential elements of a story.

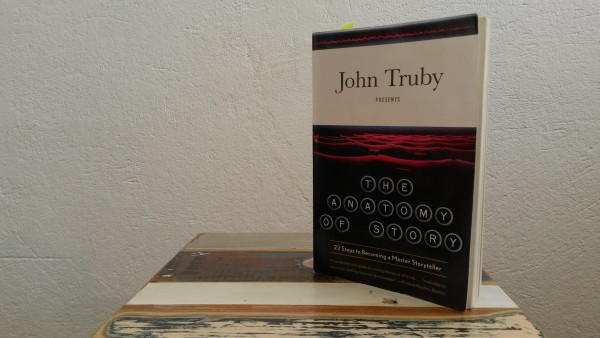

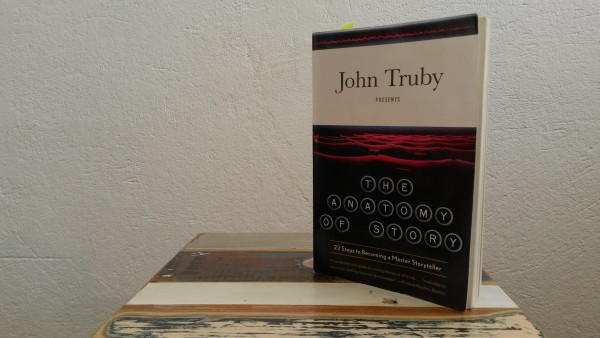

One of the many experts on storytelling to have attempted in a book to describe the essential elements of a story is John Truby.

In The Anatomy of Story (2007), Truby identifies 22 steps in any protagonist’s narrative, which may play into four aspects of the story: character, plot, story world, and moral argument. Thankfully, Truby does not insist that every story must follow the template strictly and contain all 22 steps. He does, however, identify as critical that the story show seven attributes of a main character and their storyline: (more…)

If you dont know what your story is really about, start finding out now (and don’t stop).

By Amos Ponger

Mankind’s Stories

The human ability of creating stories and the consumption and absorption of stories are very deeply connected to the core of our civilizations. Our efficiency as a species and cooperation in all scales of human endeavor rely on our ability to tell, decode, understand, and believe in stories.

Story has been so important for mankind’s cooperation, development and the way humans have understood themselves that all of our grand evolutions and revolutions – from the agricultural, religious, economic and cultural revolutions, the invention of money and law, the renaissance and humanism, the American, French and Russian revolutions, modernism, to socialism and capitalism – have actually happened through processes of rewriting collective Story. Revolutionaries and evolutionaries from Moses through Jesus, to Buddha, have actually risen upon a grand scale transformation of how humans understand themselves and cooperate with each other. And that has been done by story. Often the seeds of politics of whole centuries had actually been sown by poets, philosophers and prophets. STORYTELLERS.

Your Story

Now, even if you don’t plan on a revolution(more…)

Why The Hero Is Never Alone.

Allies Embody the Principle of Cooperation

Despite their complexity and diversity, there are essentially only three different kinds of human relationships.

That’s right, if you take a step back and try to categorize human interactions, you’ll find three distinct types. Biologists know this, because the principle applies to any species that lives in groups. Within the group, three types of behavior may be observed:

- individuals cooperate with each other

- individuals compete with each other

- individuals mate

Evolutionary biologists describe a spectrum of individual to group selection. Some animals will typically try to maximize their individual gain, as exhibited in behaviors such as taking the biggest share of food or the best space for offspring, without regard for other animals in the group. On the other hand, some species have evolved social organizations in which individuals may act purely for the group’s benefit rather than individual gain. Think of ants, bees, or termites.

Interestingly, on this spectrum between profit maximization and altruism, homo sapiens sit pretty much exactly in the middle. Humans are genetically programmed to selfishness, to seek what is perceived as best for oneself and one’s immediate family, and at the same time have a strong and innate instinctive and natural urge towards cooperation and social behavior – which ultimately also increases our survival chances.

Cooperation, neighborliness, charitable behavior, acts of kindness – even if they costs us, they generally make us feel better and they make life in the tribe, clan, or community so much easier. Mind you, we do like to look after number one. We’re not going to simply give up our salaries, our homes, our lifestyles. Our own needs and those of our families come first. Who is not aware of this dichotomy?

The pull in opposite directions between egoism and altruism is perhaps one of the specifics of human beings as a species that has caused us to evolve abstract thought processes as well as complex societal and cultural forms. It also sheds light on basic principles of storytelling such as conflict. (more…)

Archetypal Antagonism in Documentary Film and Fiction

by Amos Ponger of Mrs Wulf Story Consulting

Stories are intricate mechanisms

Documentary film is a powerful genre that draws much of its energy from the material of real-life action. Consuming documentaries, we as spectators often ignore the fact that documentaries, like fiction, are a constructed clockwork of storytelling. Since the digital revolution, the amounts of raw material for documentary productions have probably grown tenfold, shifting much of the dramaturgical construction work to the editing room. Dealing with hundreds of hours of material you may say that 90 percent of the editing work in documentary film is “finding the story“, discovering what your story is about.

One issue editors often encounter while working on the narratives of documentary films is that many directors tend to neglect the importance of understanding and designing their antagonist or their antagonistic powers, the Antagonism.

Sure, you love your protagonists. You identify with their strivings and journeys, and you as a storyteller have probably given a lot of thought to making them appealing to your audience, giving the audience someone they can identify with. Your protagonists may be an inspiration to you, or you may yourself strongly identify with them, you may share or appreciate some of their characteristics and values.

At the same time you have probably not given your Antagonist/m the same attention. Have you? (more…)

by Amos Ponger

A pledge to transformational storytelling

Working for over 20 years as an award winning film editor and story consultant, Amos Ponger studied film science, cultural sciences, art history and multidisciplinary art sciences at The FU Berlin, Humboldt University Berlin and the Tel Aviv University. He has a Master’s degree from the Steve Tisch School of Film in the Tel Aviv University, worked as an editing teacher in two Israeli film academies, is senior advisor to our story development tool Beemgee.com, and recently co-founded the story consulting service Mrs Wulf. Book his services directly here.

The Transformational Process of Creating a Great Story

We all know that creating a great story is a process that can sometimes take many months and even years to fulfill.

If you talk to professional writers they will probably tell you that they have complex relationships with these processes of writing. Involving dilemmas, fear and joy, suffering and excitement. And that these self-reflexive processes are also processes of self-exploration.

Yet many writers, scriptwriters, filmmakers tend to put a lot of energy into their external journey towards completing their story, focusing on drama, act structure, “cliff hanging”, while neglecting minding their own internal processes on their journey.

What many film and story editors encounter while working with directors and writers is that authors and directors tend to have a very strong drive. They endure months in writing solitude, or filming in deserts, storms, war zones, perhaps even putting themselves in danger in order to realize their artistic vision. Yet at the same time very often they have a remarkable incapability of explaining WHY they HAVE to do it, and can only do so in very vague terms. (more…)

A plot arises out of the actions and interactions of the characters.

On the whole, you need at least two characters to create a plot. Add even more characters to the mix, and you’ll have possibilities for more than one plot.

Most stories consist of more than one plot. Each such plot is a self-contained storyline.

The Central Plot

Often there is a central plot and at least one subplot. The central plot is usually the one that arcs across the entire narrative, from the onset of the external problem (the “inciting incident” for one character) to its resolution. This is the plot that is at the(more…)

The term motif refers to any recurring element – in storytelling as in music or other arts.

Examples of elements that turn up repeatedly within a whole are an image on a tapestry or a particular sequence of notes in a symphony. The dispersal of these elements creates a pattern. It is therefore part of the artist’s craft to have some sort of design principle determine this pattern.

What motifs do

Motifs do not make a plot. But since they make patterns they are part of the structure of a story. And they help add a layer of meaning.

In other words, if a motif is present excessively in the first half of a story, and hardly at all in the second, then the author had better be aware of a reason for this uneven distribution. The distribution – the pattern – carries meaning to the audience. Remember, the audience yearns for meaning, is always striving to understand what the story is trying to convey at any given point. This demand for some sort of raison d’être for each element of a story, or for a sense of order within the whole, may well be unconscious to the audience much of the time, but ultimately the experience of the story is more satisfying when the audience can work out reasons and meaning.

In stories, motifs can be almost anything. Objects, actions, metaphors, symbols, colours, or images can be motifs. What defines an element as a motif is the systematic deployment within the story rather than the thing itself.

How motifs work

Motifs work best when(more…)

Theme is a binding agent. It makes everything in a story stick together.

To state its theme is one way of describing what a story is about. To start finding a story’s theme, see if there is a more or less generic concept that fits, like “reform”, “racism”, “good vs. evil”. The theme of Shakespeare’s Othello is jealousy.

Once this broadest sense of theme is established, you could get a little more specific.

The theme is the expression of the reason why THIS story MUST be told! The theme of a story holds it together and expresses its values.

Theme may therefore be seen as an implicit message. But make sure that the message remains implicit, allowing the audience to understand it through their own interpretation.

Since a theme is usually (though not always) consciously posited by the author, it has some elements of a unique and personal vision of what is the best way to live. At best, this is expressed through the structure of the story, for instance by having the narrative culminate in a choice the protagonist has to make. The choices represent versions of what might be considered ways to live, or what is “right”.

But beware! This is a potential writer trap. See below.

How story expresses theme

Theme is expressed, essentially, through the audience’s reaction to how the characters grow. A consciously chosen theme seeks to convey a proposition that has the potential to be universally valid. Usually – and this is interesting in its evolutionary ramifications – the theme conveys a sense of the way a group or society can live together successfully.(more…)