Think you know world literature? How many of these classics have you read?

You have likely heard of The Divine Comedy, of Don Quixote, of Shakespeare – but have you heard of the Three Kingdoms? Of Sun Wukong? Of Cao Xueqin?

We asked ourselves, how are stories that had no contact with the western way of composing narratives different? Are the principles of storytelling really universal across cultures? Our idea was to find out by taking a look at classical Chinese literature. We discovered a number of interesting aspects to the Chinese way of telling stories, and have summarised them here.

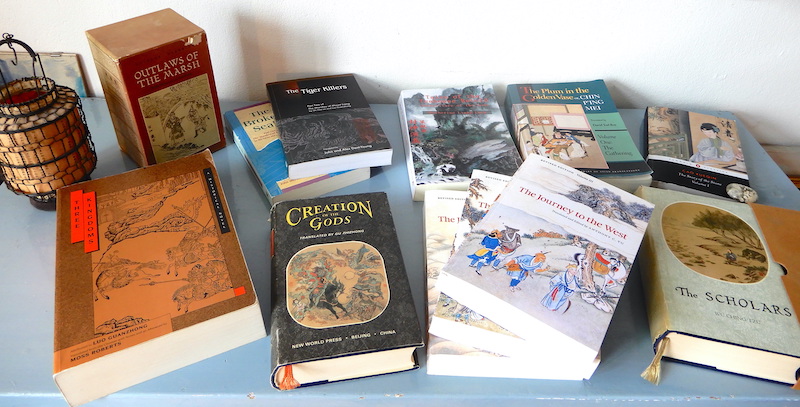

In this post, we’ll tell you about the novels we read. Each was a revelation in its own way. The long-form novel came along quite suddenly in China just over 500 years ago. Generally recognised as the first great Chinese novel is Three Kingdoms, which appeared around 1494 CE. The most modern of the novels we’re considering here was published around 1760. That means we’re looking at Ming and Qing dynasty literature.

So which classical Chinese novels should you read? Here’s our list of favourites.

Our Top 7 Classical Chinese Novels

Nr 1

Journey to the West aka Monkey aka Xī Yóu Jì

Attributed to Wu Cheng’en

Appeared: 1592 CE

Set: 7th century CE

Length: approx. 1600 pages in English translation

Chapters: 100

Magic Score: ***

What’s so special about Journey to the West?

If you’re only going to read one of the great classical Chinese novels, make it this one. The hero Sun Wukong is also known simply as Monkey, and the origins of this figure can be traced back to the Hindu god Hanuman from the Ramayana, so by now this character is about two and a half thousand years old. His immortality seems secure – Sun Wukong alias Monkey is more famous and beloved in Asia than, say, Don Quixote is in the western world, and tremendously influential in popular culture. It is hard to conceive how well-known and prevalent the novel Journey to the West is. People in the UK and Australia might remember the TV series Monkey! One of the world’s most successful manga comic series, Dragon Ball, explicitly takes motifs from Journey to the West, and the name of the hero with the monkey tail Son Goku is the Japanese translation of Sun Wukong. Even today there are big-budget movie versions and TV adaptations of Monkey’s story – currently on Netflix is a (terrible) spin-off The New Legend of Monkey. There are computer games, and Lego has recently brought out sets based on the Monkey King.

At first glance, the story seems like a quest, which gives it a narrative drive that by Chinese standards is surprisingly simple. A pilgrim is given the mission to set forth to the West (i.e. India) to attain sacred scriptures from Buddha’s holy mountain in order to introduce Buddhism to China. He soon gathers three followers with supernatural powers (four if you include the horse who is actually a dragon). The irascible Monkey is the chief disciple and the real hero of the tale. He is capable of 72 different transformations. While he is extremely strong and wily, his actions get him into trouble again and again. His adventures with monsters and his banter with second disciple Pigsy make for much of the excitement and humour in the book.

The novel appeals to children, adults, as well as serious scholars since it has so many elements. According to translator Anthony Yu, the entertaining adventure is steeped in traditional alchemy and it’s deeper message concerns the value and importance of syncretism, the parallel acceptance and partial merging of the three main belief systems in China: Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism.

Despite it’s length, the novel exhibits great symmetry, and Monkey’s character goes through a discernible development as he learns humility. He starts off by creating havoc at the Jade Emperor’s heavenly court, returns there to politely ask a favour in chapter 51, and by the end is rewarded with an official posting in heaven.

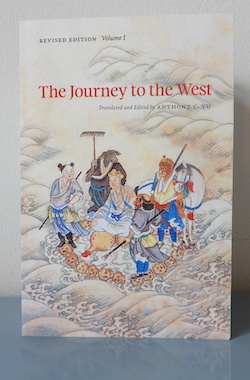

Version to read:

We read the unabridged annotated translation in four volumes by Anthony Yu and loved it! Also available is a very much shortened version as a Penguin classic.

Nr 2

Three Kingdoms aka Sānguó Yǎnyì

Attributed to Luo Guanzhong

Appeared: 1494, presumed to have been written about 100 years earlier

Set: 3rd century CE

Length: approx. 1000 pages in English translation

Chapters: 120

Magic Score: *

What’s so special about Three Kingdoms?

If you’re only going to read one of the great classical Chinese novels, make it this one. The mighty Romance of the Three Kingdoms is a historical novel based on a famous record of historical events from the third century. The astonishing novel has more pages and more battles than War and Peace, is full of military details, and has hundreds of characters. In China, Three Kingdoms is held in as high regard as the works of Shakespeare in Britain, and its influence can hardly be overestimated. Where Journey to the West expresses how the huge nation of China feels towards religion, Three Kingdoms does as much or even more for China’s sense of national identity.

“Here begins our tale. The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been.” So opens the sprawling epic. 120 chapters later we read, “The empire, long united, must divide, and long divided, must unite.”

The symmetry is not just in the surface texture. At the beginning of the novel, the world is feudal, ruled by numerous warlords fighting over greater or lesser regions. The Emperor is a weak figure with no political control over the many territories. By the middle of the novel, the three contending kingdoms have formed. At the end, the huge Chinese empire is finally united under a new dynasty. Throughout, the novel hammers home the desirability of unity over division. A strong ruling emperor with a powerful military and efficient civil service is equated with stability, a healthy state.

The story begins with a kind of prelude concerning the rebellion of the so-called “yellow scarves”, which takes up the first chapters. The hidden hero of the story, the almost undefeated strategist Zhuge Liang, is not introduced until chapter 36 (this is unlikely to be coincidence – more on the significance of numbers here) and dies in chapter 104. So we have a long “intro” before the main story begins. The attainment of the goal, the unified kingdom, is reached not by any of the main characters, they don’t live to see it, but in a kind of “outro”. The third contender for the empire, Sun Quan, dies in chapter 108 (again, surely significant), the other two way beforehand in the narrative. Actually, a long denouement is not uncommon in Asian stories, which rather than merely providing a quick and neat resolution may contain a whole new story arc before wrapping things up.

The ostensible baddy in Three Kingdoms is the opportunistic Cao Cao. His scintillating character is sharply defined, his ruthlessness set up in one of his first scenes where he not only kills the whole family of his host by mistake, but also his accomplice in this unfortunate crime, just to make sure that he will never be discovered. But Cao Cao isn’t really a villain. He may be nasty and ambitious, but he is not evil.

Three Kingdoms is not a “gods and demons” fantasy like Journey to the West, being instead a much more realistic and down to earth historical novel. The possibility of the supernatural is set up in an early chapter, then no more magic occurs until well into the second half. This long phase of gritty realism makes the appearance of Lord Guan’s ghost in chapter 77 all the more shocking and haunting, a terrifically memorable scene. Also some of the major set pieces, such the vicissitudes of the great Battle of the Red Cliffs, are so powerful that they stick in the mind for ever more.

Version to read:

We read the unabridged annotated translation by Moss Roberts, and loved it. The earlier translation by C.H. Brewitt-Taylor glosses over some of the stuff that would be hard for a western audience to understand and aims to be accessible, at the expense of some authenticity. Brewitt-Taylor gives the immortal opening as, “Empires wax and wane; states cleave asunder and coalesce.”

Nr 3

The Story of the Stone aka The Dream of the Red Chamber aka Hónglóumèng

by Cao Xueqin

Appeared: 18th century CE

Set: 18th century CE

Length: approx. 2300 pages in English translation

Chapters: 120

Magic Score: **

What’s so special about The Story of the Stone?

If you’re only going to read one of the great classical Chinese novels, make it this one. The Story of the Stone, or Dream of the Red Chamber, is a strong contender for the title “greatest novel ever written”. Is it a love story? Is it a coming of age story? Is it the story of the decline and fall of a great family? A quest for enlightenment? Or an autobiography? The Dream is all of these things and much, much more. Domestic realism, political allegory, or mystical journey – it’s all in there. The gigantic and mind-boggling novel defies ready interpretation and can be understood in many ways. Fans call themselves ‘redologists’, and scholars continue to be puzzled by the open nature of the narrative’s meaning.

The novel is a quantum leap in Chinese literature, because for the first time the text draws attentions to itself as a text. Lip service is still paid to the wiles expected of the traditional storyteller (with, for example, cliffhangers attached somewhat mechanically onto the chapter endings), but far more experimental stuff is going on in the narration. Indeed, it is unclear who the narrator really is. It could actually be the stone telling the story. Certainly the stone transforms, and might be the main character Bao-yu himself, or the jade that he wears around his neck, which was supposedly in his mouth at birth. Then again, this jade pendant might be something like the point of view character. The novel opens with the snail goddess Nuwa, which is interesting because the same deity kicks off the action of another classic, Investiture of the Gods (see below). In the first chapter of the Dream, she has thirty-six (there’s that number again) thousand stones, and while repairing the firmament leaves one stone unused. This stone is imbued with life, is found by a Taoist immortal and a Buddhist monk, and then by yet another character (called Vanitas) who inscribes the story onto it, the very story which we are reading as a record perused and edited and divided into chapters, so the text itself claims, by none other than the actual author Cao Xueqin. The first chapters are dizzying, perplexing, fascinating frames within narrative frames.

Considering that The Story of The Stone appeared around 1760, it is in fact contemporaneous with Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (though there is of course no way the two authors could have known of each other). The Story of the Stone is way earlier than Ulysses by James Joyce, yet it prefigures ideas and techniques used in such groundbreaking western novels and, like Joyce’s great works, may be seen as “the book as world”.

All of the mysticism and weirdness of the narrative frame contrasts starkly with the bulk of the novel, which is for the most part very down to earth and domestic. Some of the relationships between the characters are emotional and tender as in no earlier Chinese novel. Never before in Chinese stories have such private, playful and intimate scenes been written as we find here. Indeed, the private versus public self is one of the main themes, perhaps the main theme of the entire story.

Furthermore, The Story of the Stone has female characters in the forefront, notwithstanding that the main character is male. There are twelve women whose fates we follow, and in fact many more when we include the grandmother and all the maids, who are presented with just as much loving detail as the family members. The women are all distinct and mostly sympathetic in their ways, whereas the men fare more badly, being – with a few exceptions – either doltish or boorish. Men are “mud” whereas women are “water”.

All this is far more than a Chinese Downton Abbey, not least since it is suffused with a sense of loss and melancholy. The world described so meticulously was one that the author once enjoyed during his youth, but which exists no more, for such high society has crumbled, and Cao Xueqin wrote his novel in poverty. The atmosphere of nostalgia may have made some Chinese readers in the Qing dynasty think of the “golden days” of the Ming era before the Manchus took over. For modern western readers, the mood may be reminiscent of Remembrance of Things Past by Marcel Proust, with touches even of Vladimir Nabokov’s yearning for the lost world of his childhood.

The novel’s effeminate, almost (but really not quite) androgynous hero Bao-yu may be understood to be on a quest to discover his own (stone) identity or spiritual awakening and enlightenment. But the story seems to break all the usual storytelling rules because the nearer he comes to resolving this quest, the less he actually does. In many ways, he is – externally, at least – passive rather than active. We could speculate about the Taoist concept of inaction as set against the Confucian sense of public propriety, but more interesting still is that the novel, especially after the halfway point, develops a sense of narrative drive despite its hero’s failure to act. Hamlet took till the middle of his story to lunge into action. Bao-yu doesn’t really get going at all. Yet the page-turning tension rises inexorably.

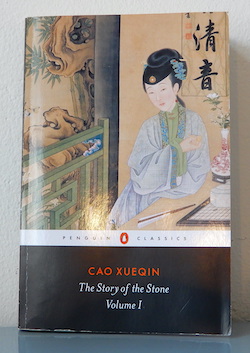

Version to read:

Unabridged translation in five volumes by David Hawkes and John Minford.

Nr 4

Investiture of the Gods aka Creation of the Gods aka Fēngshén Yǎnyì

Attributed to Xu Zhonglin

Appeared: 1605 CE

Set: 11th-3rd century BCE

Length: approx. 1200 pages in English translation

Chapters: 100

Magic Score: ***

What’s so special about Investiture of the Gods?

Investiture of the Gods features the nastiest villain in Chinese literature. King Zhou is gruesome beyond belief. He has a big toaster made, for instance, in which court advisors he doesn’t like get toasted to death.

Interestingly, his evilness is tempered by the fact that it is not inherent to him but brought about by an external force.

The story begins with the King visiting the temple of the snail goddess Nuwa and by chance catching a glimpse of the deity. (The topos is like the story of Actaeon and Diana in Greek mythology – Actaeon also comes to a bad end, but Diana’s punishment is nothing like as far-reaching as Nuwa’s). King Zhou is so overcome by emotion at the beauty of the goddess that he feels the urge to scrawl a poem about it on the temple wall. This bit of graffiti so offends Nuwa that she sends a fox spirit after him with the specific instruction to ruin him and with him the Shang dynasty, but without harming innocent people. The fox spirit takes over the body of a young woman, Daji, and thus becomes the King’s concubine. She then begins to poison his brain. He becomes utterly infatuated and enthralled by the concubine Daji, neglects the affairs of state, and gradually becomes more and more wicked.

Hence King Zhou is not really evil, for all his snake pits and mutilations, because he is not himself. The goddess is by no means evil, her mistake is not controlling the overly zealous fox spirit. The wickedest character is the fox spirit, whose fault is taking her job too seriously and, in the form of Daji, forgetting or ignoring the goddess’ injunction not to let others come to harm.

The real theme of Investiture of the Gods is not the battle between good and evil, but the conflict within each of the King’s subjects concerning their own sense of loyalty. Since they are his subjects, his advisors and his military staff must be loyal to their King. This is an absolute given. However, it becomes clear that the King is acting in detriment to the welfare of the dynasty and the state. Advisors who point this out to the King are, at Daji’s behest, put to death in ever more appalling ways. Gradually, a rebellious force consolidates under Jiang “Baby Tooth” Ziya, who is destined by heaven to establish the next dynasty, the Chou.

The historical Shang dynasty fell and was replaced by the Chou dynasty around the 11th century BCE. Investiture of the Gods belongs like Journey to the West to the “gods and demons” genre. It is full of supernatural magic and demonic characters, and the plot is action-packed with many conflicts and battles. The serious underlying question – at what point is it right to forsake your loyalty and turn against your master? – is posed again and again, with each major character making the choice. The problem is essentially insoluble. The indicator for the right course of action is discovering the true will of heaven. It is preordained that Shang will fall, so even Nuwa was acting in accordance with preordained destiny in triggering the action that will lead to the establishing of a new dynasty.

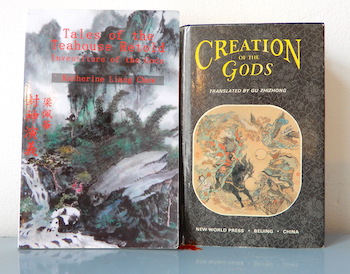

Version to read:

We read the abridged translation of the first 46 chapters by Katherine Liang Chew called Tales of the Teahouse Retold and for the rest, the out of print Creation of the Gods translated by Gu Zhizhong.

Nr 5

Water Margin aka Outlaws of the Marsh aka The Marshes of Mount Liang aka All Men Are Brothers aka Shuǐhǔ Zhuàn

Attributed to Shi Nai’an, completed by Luo Guanzhong

Appeared: 14th century CE

Set: 12th century CE

Length: approx. 2000 pages in English translation

Chapters: 100 (also 120 and 70)

Magic Score: *

What’s so special about Water Margin?

Water Margin, like the later Investiture of the Gods, is about loyalty. The 108 men who become outlaws band together not because they are criminals or villains per se, but because they feel wronged by their superiors or the state. If they had been treated properly, they feel, they would not have to go into the exile they have chosen for themselves in the impenetrable marshes of Mount Liang.

The 108 “heroes” are quite distinct from one another, and the interplay of their relationships as they set up the hierarchy in their growing organisation is clearly drawn. A western reader is unlikely to feel the same way reading this novel as Chinese readers, for whom many of the characters and situations are familiar, and already were when the book appeared. Much of the raw material of the novel, most characters and many of their adventures, had been recounted in storytellers’ tales, folk legends, and plays for centuries prior to the novel, having some basis in actual historical events.

The innovation in the novel is the addition of tremendous complexity and layers of meaning through moral ambiguity. For instance, many of the more upper class members of the band do not join voluntarily but are tricked or forced by increasingly drastic ruses, one of which even involves the cold-blooded killing of an innocent child, the ward of a man the chief of the outlaws wants among their number. The chief, Song Jiang, was generally regarded as a hero (along the lines of Robin Hood), and the force of this conception is so strong that he is often still considered that today. But in the novel his heroism is undermined by a darker as well as weaker side of his character. Similarly, his contrasting foil character Iron Ox Li Kui is generally seen as a rough-and-ready free spirit, but in the novel comes across more and more as a psychopath. The increasing power of the band of outlaws, initially just a few local petty brigands, grows to such an extent that the order of the entire empire is disturbed, and this play with order (the confucian order of the universe, if you will) versus chaos, rule of law versus havoc, is very much a layer of significance, as is the ultimate emptiness that the growing weakness within the gathering strength of the outlaws leads to.

The narrative flows on spatially, following first one character’s story of joining the outlaws and then another’s, with a meeting taking place as a handover of the action, after which we follow the next prospective outlaw’s story. These transitions – ‘billiard ball’ shifts in narrative focus – go a long way towards establishing a sense of unity to the work despite the great many characters and their respective individual stories.

Water Margin is the most graphically violent of the classical Chinese novels, which makes it unsuitable for children. Nonetheless it enjoys tremendous popularity in Asia to this day, with TV, comic, and video game adaptations.

Version to read:

We read the unabridged translation of the 120 chapter version in five volumes by John and Alex Dent-Young. Also to be found is the 100 chapter version translated without the poems by Sidney Shapiro. Harder to find, though worth snapping up if you do, is Pearl S. Buck’s atmospheric translation of the 70 chapter version, called All Men Are Brothers. Shapiro’s and especially Buck’s language may be more elegant, but both versions perhaps leave a false impression of the original because the poems are missing and that amazing transitional action is edited out.

Nr 6

The Scholars aka Rúlín Wàishǐ

by Wu Ching-Tzi

Appeared: 1750 CE

Set: 15th-16th century CE

Length: approx. 600 pages in English translation

Chapters: 55

Magic Score: *

What’s so special about The Scholars?

The Scholars is relatively short in comparison with the other novels in this list. Like Water Margin, it does not have a few central characters around whom the action is centred. Instead, the novel tells of many different characters with the idea of presenting the entire gamut of the scholar class. (More on the role of scholars in China here).

Because there are many different types of scholars, there are many kinds of stories in the book. Some of the more adventurous ones are reminiscent of episodes from older classics such as Water Margin, with scholars slaying tigers or fighting each other. But most of them are decidedly unheroic, and concerned with rather mundane issues and conflicts.

All this does not mean that the book is simply a string of episodes connected merely by a common topic. There is a narrative frame which presents a sort of ideal scholar worthy of emulation, against whom all of the characters in the novel fall short. As with Water Margin, the narrative seeks unity by being carefully constructed to have transitions that hand over the action without any break from character to character.

Most interesting is that the overall narrative structure exhibits the seven tenths rule (more on structure in Chinese novels here). The highpoint of scholarly virtue, the nearest any of the characters come to the paragon set up in the prologue, is when some of them pool their resources to build a temple. This is achieved in chapter 36 and 37, seven tenths of the way through the book. In the following chapters concerning the years after that, we read of a decline in the scholarly tradition.

Interesting is that the material seems to be more or less entirely original. Unlike the earlier novels, which all take extant story material as the basis or starting point, the many plots and storylines of The Scholars are completely invented. This alone makes The Scholars a landmark in the history of Chinese fiction.

Version to read:

We read the translation by Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang

Nr 7

The Plum in the Golden Vase aka The Golden Lotus aka Jīn Píng Méi

Author unknown

Appeared: 1610

Set: 12th century CE

Length: approx. 2000 pages in English translation

Chapters: 100

Magic Score: *

What’s so special about The Plum in the Golden Vase?

The Plum in the Golden Vase is the most sexually explicit of the classic Chinese novels. It has exactly 72 sex scenes. However, the novel cannot really be considered either erotic or pornographic, since the sex is described in such terms as to make it rather mechanical and unexciting. That said, the topic of sex as debauchery is ubiquitous in the book, with dense and frequent word-play, innuendo, and jokes – most of them hard to translate.

The starting point of the narrative is an episode from Water Margin. In the earlier work, the despicable Ximen Qing is killed by Wu Song for being the cause of Wu Song’s brother’s death; in Plum in the Golden Vase, Ximen Qing survives and manages to have Wu Song banished. So the first chapters are a retelling, but then the bulk of the story is invented fiction. This makes The Plum in the Golden Vase notable in the history of Chinese literature for the author making up the story, rather than basing it on older material.

While earlier novels show acts of heroic virtue, Plum in the Golden Vase shows only depravity and corruption. The theme is stated repeatedly and explicitly, as for instance “In this world the heart of man alone remains vile”. There is simply no likeable character in the book – or at least there are none we are invited to feel sympathy with. Quite possibly, The Plum in the Golden Vase is a distinct indictment of the ruling class of the time of its writing, perhaps even a roman a clef. The novel ostensibly describes a household a few centuries prior to the novel’s publication, but this may be an allegory for the contemporary imperial court. The negative example set in the novel can be understood as an indictment of private as well as public immorality as leading to disorder and ruin, for the individual and for society.

Version to read:

We read the unabridged translation in five volumes by David Tod Roy. His annotations are primarily of interest to scholars.

We sorted these novels into their order of appearance as well as the time in which the stories are set in this Beemgee project.

So what are the differences between Chinese storytelling and western storytelling? If you are considering reading any of the novels in our list, we recommend 18 things to look out for in the classical Chinese novel.

Test drive the Beemgee author tool now: